Ir Med J. 2007 Feb;100(2):373-4

Abstract

Penrose’s Law states that as the number of psychiatric inpatients declines, the number of prisoners increases. We studied data from the annual census of psychiatric inpatients and prison statistics in Ireland. Between 1963 and 2003, the number of psychiatric inpatients decreased by 81.5% (a five-fold decrease) and the average number of prisoners increased by 494.8% (a five-fold increase) (Spearman’s rho=-0.992, P<0.001). The absolute decline in psychiatric inpatients greatly exceeded the increase in prisoners. This net de-institutionalisation appears particularly marked in Ireland compared to England; this may relate to ecological study designs or differences in prison, health or re-institutionalisation practices.

Introduction

In the early twentieth century, Professor Lionel Penrose studied the relationships between the number of individuals in mental ‘institutions’ and rates of crime in 14 European countries.1 Penrose identified that the number of individuals in mental ‘institutions’ was inversely correlated with:

- the number of murders,

- the number of live births per 1000 population and

- the number of individuals in prison.

Over the remainder of the twentieth century, it was the third inverse relationship that proved the most robust 2,3 and eventually become known as Penrose’s Law; i.e. that as the number of psychiatric inpatients declines, the number of prisoners increases. This paper uses ecological data to examine the validity of Penrose’s Law in Ireland between 1963 and 2003.

Method

Data on the number of psychiatric inpatients in Ireland were obtained from the annual census of inpatients in psychiatric hospitals and units, performed on 31st March each year between 1963 and 2003 by the Medico-Social Research Board, Health Research Board and Department of Health and Children.4,5 This census includes all individuals in public and private psychiatric hospitals and inpatient units but does not include individuals with mental illness in community residential accommodation or medical units of prisons. Data on the daily average number of prisoners in Irish prisons between 1963 and 2003 were obtained from the crime and criminal justice system database assembled by O’Donnell et al 6, based on annual reports and data collection from the Irish court and prison services. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.7

Results

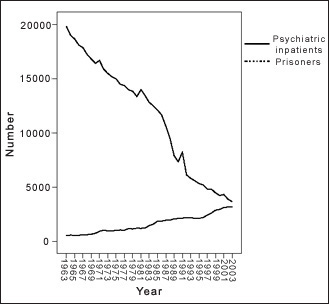

Between 1963 and 2003 the number of individuals in Irish psychiatric units and hospitals decreased from 19,801 to 3,658; this is a decrease of 16,143 individuals or 81.5% (i.e. a five-fold decrease). During the same period the daily average number of prisoners in Irish prisons increased from 534 to 3,176; this is an increase of 2,642 individuals or 494.8% (i.e. a five-fold increase). There was a statistically significant inverse correlation between the number of individuals in Irish psychiatric units and hospitals and the daily average number of prisoners in Irish prisons over this period (Spearman’s rho=-0.992, P<0.001) (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 Numbers of psychiatric inpatients

and prisoners in Ireland, 1963-20034,5,6 |

Discussion

This ecological analysis showed a strong inverse relationship between the number of individuals in Irish psychiatric units and hospitals and the daily average number of prisoners in Irish prisons between 1963 and 2003. While there was a five-fold decrease in psychiatric inpatients and a five-fold increase in prisoners over this period, the absolute decrease in psychiatric inpatients (16,143) was much greater than the absolute increase in prisoners (2,642).

The strengths of this study include simplicity; the use of comprehensive, statutory national data-sets; and the availability of complete data for both variables for all years studied. Limitations include the fact that this is an ecological study which examines variables at group rather than individual level, and the absence of data on potentially confounding variables such as crime rates, mental health service developments or socio-economic changes.

An inverse relationship between numbers of psychiatric inpatients and prisoners has been demonstrated in multiple countries including England and Wales,3 Australia2 and several European countries including Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden.8 Gunn3 studied data from England and Wales between 1982 and 1997 and showed that:

- the number of psychiatric hospital beds exceeded the number of prisoners in 1982;

- these numbers converged over the course of the1980s; and

- the number of psychiatric beds came to exceed the number of prisoners by the late 1990s.

The present study suggests that a similar process has occurred in Ireland, with a steady decline in psychiatric inpatients and a steady increase in prisoners between 1963 and 2003. It is particularly notable that in Ireland the decline in psychiatric inpatients greatly exceeded the increase in prisoners, resulting in substantial net de-institutionalisation over this period.

As with most studies of Penrose’s Law, the present study demonstrates an ecological relationship between the numbers of psychiatric inpatients and prisoners; i.e. while the decline in psychiatric inpatients and increase in prisoners are observed at group level, it is not known whether the individuals who leave psychiatric hospitals are the same individuals who are subsequently imprisoned. There is, however, strong evidence of a high prevalence of mental illness in prisons: one systematic review of 62 studies from 12 countries found that 3.7% of male prisoners and 4% of female prisoners had psychosis, while 10% of male prisoners and 12% of female prisoners had major depression.9 In Ireland, the six-month prevalence of psychosis in life-sentenced male prisoners is 7.1%.10

This study demonstrates that psychiatric de-institutionalisation in Ireland has occurred at the same time as increases in the Irish prison population; this is analogous to the pattern observed in England in the 1980s and 1990s. However, the Irish data show that the decrease in psychiatric inpatients over this period greatly exceeds the increase in prisoners; this net de-institutionalisation appears particularly marked in Ireland compared to England. The differences in these trends may relate to differing capacity limitations in prison systems in the two jurisdictions; differences in criminal and mental health law in the two jurisdictions; differences in mental health provision between the two health systems; or the emergence of different forms of re-institutionalisation in the two countries.

Future studies on this topic in Ireland could focus on:

- the pathways followed by specific individuals within and between the psychiatric and prison systems, attempting to trace the relationship between psychiatric de-institutionalisation and imprisonment at individual level;

- the possibility of other forms of re-institutionalisation in Ireland, such as hostel placement; and

- the relationship (if any) between psychiatric de-institutionalisation and rates of homelessness in Ireland.

Correspondence:

Brendan Kelly,

Department of Adult Psychiatry, University College Dublin,

Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, 62/63 Eccles Street, Dublin 7,

E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Penrose LS. Mental disease and crime: outlines of a comparative study of European statistics. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1939; 18: 1-15.

- Biles D, Mulligan G. Mad or bad? The enduring dilemma. British Journal of Criminology 1973; 13: 275-279.

- Gunn J. Future directions for treatment in forensic psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry 2000; 176: 332-338.

- Daly A, Moran R, Walsh D, Kortolova O’Doherty Y. Activities of Irish Psychiatric Services 2003. Dublin: Health Research Board, 2004.

- Mental Health Commission. Annual Report 2004. Dublin: Mental Health Commission, 2005.

- O’Donnell I, O’Sullivan E, Healy D. (eds.). Crime and Punishment in Ireland 1922 to 2003: A Statistical Sourcebook. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration, 2005.

- SPSS Inc. SPSS 12.0 Base Users Guide. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Regents, 2003.

- Priebe S, Badesconyi A, Fioritti A, Hansoon L, Kilian R, Torres-Gonzale F, Turner T, Wiersma D. Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison

of data on service provision from six European countries. British Medical Journal 2005; 330: 123-126.

- Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 2002; 359: 545-550.

- Duffy D, Linehan S, Kennedy HG. Psychiatric morbidity in the male sentenced Irish prisons population. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 2006; 23:

54-62.