|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fida Magdi Ali,N Farah,V O'Dwyer,Clare O'Connor,M Kennelly,MJ Turner

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):57-9

FM Ali, N Farah, V O'Dwyer, C O'Connor, MM Kennelly, MJ Turner

UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital, Dublin 8

|

|

Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has important maternal and fetal implications. In 2010, the Health Service Executive published guidelines on GDM. We examined the impact of the new guidelines in a large maternity unit. In January 2011, the hospital replaced the 100g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) with the new 75g OGTT. We compared the first 6 months of 2011 with the first 6 months of 2010. The new guidelines were associated with a 22% increase in women screened from 1375 in 2010 to 1679 in 2011 (p<0.001). Of the women screened, the number diagnosed with GDM increased from 10.1% (n=139) to 13.2% (n=221) (p<0.001).The combination of increased screening and a more sensitive OGTT resulted in the number of women diagnosed with GDM increasing 59% from 139 to 221 (p=0.02).This large increase has important resource implications but, if clinical outcomes are improved, there should be a decrease in long-term costs.

Introduction

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) carries lifelong consequences for the mother and her offspring1,2. It is associated with an increase in perinatal complications, including fetal macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycaemia. It is also associated with an increase in obstetric interventions such as induction of labour and caesarean section, which may in turn increase maternal morbidity. In the long-term it increases the risk of metabolic syndrome for both mother and baby, which may manifest itself later in life in the form of diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease3,4. International consensus about screening for GDM has been difficult to achieve5,6. Some experts, for example, advocate universal screening, others selective. Some advocate using an oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) with a 100g glucose load, others a 75 g. The original diagnostic thresholds for GDM were based on the subsequent likelihood of developing adult-onset diabetes mellitus and were not predictive of any specific pregnancy outcome7. Recent studies, however, have reported that maternal hyperglycaemia, insufficient to make the diagnosis of GDM, is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes8. As a result, an international consensus developed new lower diagnostic cut-off points in women for the diagnosis of GDM based on an odds ratio for adverse outcomes of ≥1.75 compared with women with normal mean glucose levels9.

In 2010, the Health Services Executive (HSE) in Ireland published national guidelines for GDM incorporating the latest international evidence. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of introducing the new guidelines in a large maternity unit.

Methods

As the new guidelines were published in August of 2010, we compared the results from the first 6 months of 2011 with the first 6 months of 2010. In 2010, screening was selective based on risk factors and a 100 g OGTT was used. The normal blood sugars were fasting <5.3 mmol/l, 1 hour < 10.0 mmol, 2 hour <8.6 mmol and 3 hour <7.8 mmol. A diagnosis of GDM was made if two or more values were met or exceeded 6. From January 1st 2011, screening continued to be based on risk factors but a 75 g OGTT was used. The normal blood sugars were fasting <5.1 mmol/l, 1 hour <10.0 mmol/l, 2 hour <8.5mmol/l. A diagnosis of GDM was made if one or more values were met or exceeded5,9. All tests were performed in a standardised way in the Perinatal Centre and the results recorded manually in a register. The clinical details of the first antenatal visit on all women screened were retrieved from the Hospital’s computerised database for subsequent analysis.

Results

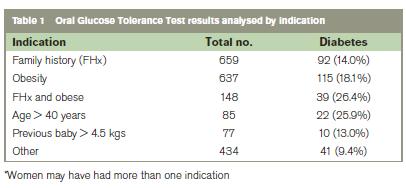

The indications for the OGTT were based on the risk factors published in 2010 and are shown in Table 1. The number of women who delivered a baby weighing 500g or more was 4289 for the first 6 months of 2010 compared with 4184 in 2011. Approximately a third of women attending antenatally were screened on a selective basis. A combination of maternal obesity and family history had the highest incidence of abnormal OGTT at 23.4%.Of women screened, the incidence of GDM was 15.1% (n=78) out of 518 women >35 years, compared with 12.3% (n=143) out of 1161 women ≤ 35 years (NS).

The introduction of the national guidelines was associated with an increase in OGTTs performed from 1375 in the first half of 2010 to 1679 in the first half of 2011 (a 22% increase) (p<0.001). Of the women screened, the number of abnormal OGTTs increased from 10.1%(n=139) in 2010 to 13.2% (n=221) in 2011 (p<0.001). The combination of increased screening and a more sensitive OGTT resulted in the number of women diagnosed with GDM increasing from 139 to 221 (a 59% increase) (p<0.02). The number of fasting glucose tests deemed abnormal increased from 51 in 2010 to 116 in 2011 (a 127% increase) (p<0.001). It follows that the number of women who should be referred postnatally for an OGTT to confirm that diabetes mellitus is not persistent will also need to increase by 59%.

Discussion

The introduction of new national guidelines in Ireland has resulted in a large increase in the number of women being diagnosed with GDM in our Hospital. The increase may be due, in part, to improved compliance with the indications for screening, but an increase is also to be expected because the threshold for making the diagnosis internationally has been lowered. Our results are similar to those reported from the West of Ireland10. A total of 12,487 women were invited to have an OGTT to screen for GDM, although only 44% attended10. Based on a 75 g OGTT at 24-28 weeks, 9.4% met the criteria for GDM using previous criteria but, 12.4% met the criteria using the new national guidelines9,10. In a large, national sample of pregnant women in the United States, it was concluded that the number of women diagnosed with GDM after the 75 g OGTT doubles in comparison with the number diagnosed with an 100 g OGTT11.

Apart from the increased direct cost of screening, this increase in the number of cases has resource implications. An increase in prevalence of GDM will increase demands for multidisciplinary care by midwives, dieticians, sonographers, obstetricians and neonatologists. There will also be an increase in direct costs for laboratory testing and pharmacological treatment in women with GDM. Potentially, it may lead to an increase in obstetric interventions such as induction of labour and caesarean section. It will also increase the number of women who require a postnatal OGTT to confirm that the OGTT has reverted back to normal. Potentially, it may increase service needs in primary care if a woman’s OGTT remains abnormal postpartum. The increase in the number of women diagnosed with GDM in 2011 may also be an underestimate. Previous studies based on either universal screening or selective screening have reported low compliance with guidelines10,11. The increased diagnosis of GDM followed by appropriate interventions to optimise maternal glycaemia should bring clinical benefits to both mother and baby13. Minimising hyperglycemia should avoid fetal macrosomia and associated shoulder dystocia, which potentially may prevent permanent brachial plexus injury (BPI)1,7. This is important clinically and BPI often results in obstetric negligence cases, which are expensive for the maternity services whether successfully defended or not. There is also evidence that maternal hyperglycaemia increases not only fetal adiposity, but also may influence the distribution of fetal adipose tissue in utero14.

In the short-term, poorly controlled maternal hyperglycemia may result in neonatal hypoglycaemia and admission to the neonatal care unit and in the long-term is associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus1,4. Hyperglycaemia also has maternal implications. Fetal macrosomia increases the risk of operative delivery, particularly caesarean section (CS)15. It may also increase the risk of induction of labour which itself is associated with an increased risk of CS. However, in an Australian multicenter randomised controlled trail, the rate of induction was higher in the treated GDM group, yet CS rates were nearly equivalent between the treated (31%) and untreated (32%) women16. In the longterm women who have GDM are more likely to develop DM later in life3. The development of DM later in life may be due in part to the poor follow-up postnatally of women with GDM. In one study, less than half (45%) of women with GDM underwent postpartum glucose testing17.

The implementation of the new national guidelines and, in particular, the management of more women diagnosed with GDM will increase the costs of maternity care in the third trimester. If implementation leads to improved glycaemic control and to a decrease in adverse clinical outcomes for both mother and her baby then it is expected that the increased short-term investment will reap long-term financial as well as clinical dividends. We plan to follow-up the 2011 cohort screened to see if the increased diagnosis of GDM leads to a change in clinical outcomes, particularly fetal macrosomia.

Correspondence: MJ Turner

UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, Coombe Women & Infants University Hospital, Dublin 8

Acknowledgements

We thank the midwifery staff in the Perinatal Centre and F Dunleavy, dietician for their assistance.

References

1. Reece AE. The fetal and maternal consequences of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonat Med 2010;23:199-203.

2. Landon MB, Mele L, Spong CY, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B et al. The relationship between maternal glycemia and perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:218-24.

3. Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1862-8.

4. Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005;115:290-6.

5. Hillier TA, Vesco KK, Pedula KL, Beil TL, Whitlock EP, Pettitt DJ. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:766-75.

6. Reece EA, Leguizamón G, Wiznitzer A. Gestational diabetes: the need for common ground. Lancet 2009;373:1789-97.

7. Landon MB. Is there a benefit to the treatment of mild gestational diabetes mellitus? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:649-53.

8. The HAPO study research group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Eng J Med 2008;358:1991-2002.

9. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, Damm P, et al. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:676-82.

10. O’Sullivan EP, Avalos G, O’Reilly M, Dennedy MC, Gaffney G, Dunne F. Atlantic Diabetes in Pregnancy (DIP): the prevalence and outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus using new diagnostic criteria. Diabetologia 2011;54:1670-5.

11. Blatt AJ, Nakamoto JM, Kaufman HW. Gaps in diabetes screening during pregnancy and postpartum. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:61-8.

12. Persson M, Winkvist A, Mogren I. Surprisingly low compliance to local guidelines for risk-factor based screening for gestational diabetes mellitus- A population based study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2009;9:53.

13. Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009:361;1339-48.

14. Farah N, Kennelly MM, Stuart B, Turner MJ. Influence of maternal glycemia on intrauterine fetal adiposity after a normal oral glucose tolerance test at 28 weeks gestation. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol 2011;157:14-7.

15. Turner MJ. Delivery after one previous cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;176:741-4.

16. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jefferies WS, Robinson JS. Effect of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Eng J Med 2005;352:2477-86

17. Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson Cl, Welsh HG, Carpenter MW. Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1456-62.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|