Introduction

Research has shown that numbers of home visits by GPs have declined in many European countrie 1,2. It was considered that this may also apply to the inner city practice observed in this study. To date there is a gap in the literature regarding home visits in general practice in Ireland. One postal survey of housecalls done by 130 Irish GPs in 1993-4 showed that Irish GPs were doing an average of 14 housecalls per week each at this time1. Another study performed in Belfast in the mid 1980’s found that GPs studied were performing between 3 and 39 new home visits and between 0 and 22 re-visits per doctor per week3. They found also that doctors were spending between 0.9 and 23 hours per GP per week conducting housecalls. Redmond et al recently found they performed a total 54 home visits in a 3 month period in Dublin, showing a much lower rate than these studies from the 1980s and 1990s4. The aim of this study is to examine the trend in home visits undertaken by general practitioners in an inner city practice.

Methods

This study of GP home visits was conducted in a computerised inner city general practice of nearly 7,000 patients with a slight predominance of private patients (57%). Housecalls were not formally triaged and patients could request their preferred doctor for their home visit. Such requests were accommodated where feasible depending on doctor availability. The number of housecalls requested at the practice from 2006-2010 was calculated to assess the trend in same. 100 housecalls done at the practice between the dates of May 6th and August 13th, 2009 were also surveyed to compile more specific data for home visits, including whether they were deemed to be medically or socially indicated by the visiting GP. Other data collected included patient demographics, the reason for the housecall, existence of chronic conditions, number of practice visits, number of visits to the out of hours services and number of housecalls requested in the preceding year. Results were analysed using a standard statistical analysis programme.

Results

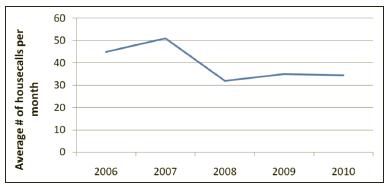

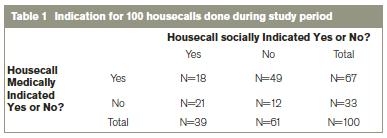

The number of housecalls done at our practice has indeed declined over recent years (see Figure 1). In 88% of the housecalls undertaken the visiting doctors considered that there was a valid medical or social indication for the home visit. Of interest 12% of housecalls were considered to have no valid medical or social reason for a home visit. In 18% of housecalls done the visiting doctor considered that there was both a medical and social reason for doing the housecall e.g. housebound elderly diabetic patient with poor social supports who is experiencing an intercurrent illness. In the opinion of the visiting doctors 21% (n=21) of the housecalls requested during the study period were done for solely social reasons, there being no medical indication for the visit in their views (see Table 1).

68% of patients visited were female, 75% were aged 65 years or over. 91% of housecalls done were to patients who hold medical cards i.e. patients entitled to free medical care under the General Medical Services scheme. For 35% of home visits the patient had no consultation at the practice in the preceding year. One patient visited at home had had 28 visits to the practice in the previous year. For 48% of the housecalls done these patients had used the out of hours services at least once in the previous year. We also explored how many housecalls each patient visited had had in the previous year. One patient had had 20 housecalls in the preceding year; the mean number of housecalls done to patients in the previous year was 5.34.

In 58% of housecalls done a note had been made in the patient’s file by the visiting doctor. Notes on housecalls were not routinely recorded prior to this study unless the visit was for a serious medical or social problem. In 23% of housecalls done the documented reason for the visit was of a respiratory nature, as categorised using the ICD-10 Classification. Of note, 87% of housecall patients had multimorbidities. The vast majority (89%) of GMS eligible patients visited had multimorbidities, this compares to 66.7% of private patients visited.

Figure 1: Average number of housecalls conducted per month from 2006-2010

Table 1: Indication for 100 housecalls done during study period

* Housecalls were judged as either medically and/or socially warranted or neither

by the visiting GP

Discussion

Bedside medicine is believed to have had it’s origins with the Hippocratics approximately 400 years BC. This was long prior to the establishment of the traditional hospital, thus ancient Greek bedside medicine was the prototype of modern primary care and the home visit5. On further consideration of the origin of the housecall it is interesting to note that in Dutch a General Practitioner is known as a “Huisarts” and directly translated this means “Home Doctor”6. It is known that housecall rates have declined in many countries1,2,7 but there have been few studies in Ireland directly examining this aspect of GP workload. Our study found that there has indeed been a decline in the number of housecalls done at our practice in recent years but the rates still remain high with expected seasonal peaks. Our rate is lower than the rate of 14 housecalls per week quoted in Boerma’s survey of home visiting in Ireland in 1993/19941 and the Mills & Reilly study in Northern Ireland in 1986 which found that GPs were performing between 3 and 39 new home visits and between 0 and 22 re-visits per doctor per week3. However our home visiting rates are still higher than that recently quoted by Redmond et al at another Dublin city GP practice4.

Van den Berg et al cite many reasons for the decline in home visiting rates. Improved efficiency, fewer urgent home visits, fewer home visits to children and changes in GP style of work with sharpening of their criteria for home visits are all believed to contribute2. It is likely that increased access to telephones and transport have also contributed to this decline. While housecall rates are declining in many countries they clearly will not disappear from our workload entirely. For example in Great Britain in 2004/2005 4% of consultations were still done in the home, this compares to 22% in 19718. In the US in the past decade, housecalls have actually experienced a resurgence9. It is known that our population in Ireland is ageing. It is projected that the number of persons aged 65 and over will almost double in Ireland by 202610. As our population ages it is likely that the demand for home visits from all members of the primary care team will increase significantly.

We believe we may be doing more housecalls than our peers in the city, there may be many reasons for this. A study of 349,505 patients in England and Wales in 2004 showed that increasing age, female gender, lower socio-economic status and higher morbidity class increased the likelihood of having a home visit11. Several other studies2,7,12 corroborate these findings. Van Royen at al noted that GPs with a more defensive attitude perform more home visits and that appointment systems were seen as important in decreasing the rate of home visits13. We may perform more housecalls than our peers because our practice is located in an inner city area of socio-economic deprivation. This is reflected in the finding that in 91% of housecalls done the patients held GMS cards. Also we found that in 68% of our housecalls patients visited were female and that the mean age of patients visited was 72 with three quarters of our housecalls having been done to patients over 65 years of age. What is also likely to impact on our housecall rate is that in 87% of our housecalls done, the patients had multimorbidities. However, other local practices are likely to have similar patient profiles. Therefore, doctor style or attitude and practice organisation e.g. lack of a practice protocol regarding housecalls must also play a significant role.

Our main study question was “did we consider that the housecalls we were doing were necessary on medical and, or social grounds?” In 12% of home visits the doctor did not deem that there was a valid medical or social reason for the housecall that was requested by the patient. The reasons for this are myriad. We would cite poor health literacy, patient expectations, inadequate use of telephone triage, lack of an established primary care team and defensive practice as reasons for this finding. 21% of the housecalls done during the study period were considered to be done for solely social reasons. This most likely reflects the lower socioeconomic group served by our practice as well as doctor behaviour and attitude in addition to patient expectations. The finding that in 18% of housecalls done the visiting doctor considered that there was both a medical and social reason for doing the housecall reflects the complexity of working in an inner city underprivileged area.

Our study shows that we felt that the majority of our housecalls were warranted and appropriate. Beyond simply providing homebound patients with access, there is growing evidence that house calls favourably influence important health outcomes and improve patient care by clarifying and identifying problems that are missed in the clinic setting9. These issues can include poor home hygiene, lack of nutritious food in the home, falls hazards, unused prescribed medication and evidence of hazardous alcohol consumption. At the University of Nottingham researchers carried out a meta-analysis of 15 studies demonstrating that home visits reduce mortality and admission to long-term nursing home care for both general and frail elderly14. It is not always recognised that housecalls can also benefit the doctor. One interesting survey of 751 primary care physicians in the US showed that doctors who frequently do housecalls are more likely than physicians who never, or only occasionally , make housecalls to feel that home visits are enjoyable, and they are less likely than occasional house callers to feel they are too busy to make house calls9. However, it is acknowledged that concerns regarding personal security, access to safe, adequate parking and time spent travelling to housecalls can negatively impact how GPs view doing housecalls. Exploration of such issues was beyond the scope of this research.

One limitation of this research is that our study numbers are small. Additionally, looking at housecall rates for one practice in Dublin may not reflect home visiting patterns in other areas of Ireland given the many determinants of home visiting rates. Six GPs at our practice subjectively assessed whether housecalls were medically or socially indicated, this may have lead to some differences in results due to differing attitudes and experience. We feel that this was a worthwhile study to perform given that the need for home visits will not disappear from the ever-increasing workload of the Irish GP. Discussion, audit, support and appropriate remuneration will be required if all primary care staff are to safely carry out this function in an ageing society.

Correspondence: A Cunney

TCD/HSE Specialist Training in General Practice, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, Tallaght Hospital, Dublin 24

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the doctors, practice nurse and administration staff of Rialto Medical Centre for their help in collecting the data used in this research.

References

1. Boerma WGW, Groenewegen PP. GP home visits in 18 European countries. Eur J Gen Pract 2001;7:132-7.

2. Van den Berg M, Cardol M, Bongers F, De Bakker D. Changing patterns of home visiting in general practice: an analysis of electronic medical records. BMC Family Practice 2006, 7:58.

3. Mills K, Reilly P. General Practitioner workload with 2,000 patients. The Ulster Medical Journal, Volume 55, No 1, pp.33-40, April 1986.

4. Redmond, P. Remembering the value of making house calls. Forum February 2010.

5. Bynum, W. The History of Medicine. Oxford University Press 2008.

6. Cassell’s Dutch Dictionary. 38th Edition, April 2008.

7. Joyce C. Trends in GP Home visits. Australian Family Physician Vol 37, No 12, December 2008.

8. National Statistics Online www.statistics.gov.uk accessed 31/07/09.

9. Kao, H, Conant, R, Soriano, T, McCormick, W. The past, present and future of housecalls. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. Vol 25, Issue 1, February 2009, 19-34.

10. Central Statistics Office, Regional Population Projections 2011-2026, 4 Dec 2008.

11. O Sullivan C, Omar, R, Forrest C, Majeed, A. Adjusting for case mix and social class in examining variation in home visits between practices. Family Practice Vol 21, No 4, Oxford University Press 2004.

12. Aylin P, Majeed A, Cook, D. Home visiting by general practitioners in England and Wales. BMJ 1996;313:207-210.

13. Van Royen P, De Lepeleire J, Maes R. Home visits in general practice: an exploration by focus groups. Arch Public Health 202, 60, 371-384.

14. Elkan R, Kendick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis BMJ 2001;323:719.