|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E Dunne,M Duggan,J O'Mahony

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2012 Mar;105(3):71-2,74

E Dunne1, M Duggan2, J O'Mahony3

1Department of Psychiatry, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

2Adult Homeless Integrated Services, Cork

3Skibbereen Medical Centre, Co Cork

Abstract

This study aimed to establish a profile of users of the mental health service for homeless in Cork, comparing this group with those attending a General Adult Service. The homeless group were significantly more likely to be male (89% v 46%), unemployed (96% v 68%), unmarried (98% v 75%) and under 65 (94% v 83%). Diagnostically, there was a significantly higher prevalence of schizophrenia (50% v 34%); personality disorder (37% v 11%) and substance dependence (74% v 19%) in the homeless service users. They were more likely to have a history of deliberate self harm (54% v 21%) and violence (48% v 10%). Severe mental illness has a high prevalence in the homeless population, with particularly high levels of factors associated with suicide and homicide. Poor compliance and complexity of illness lead to a requirement for significant input from multidisciplinary mental health teams members.

|

|

Introduction

The Housing Act, 19881, sets out the legal definition of homeless persons to include those for whom no accommodation exists, which they could be reasonably expected to use, or those who could not be expected to remain in existing accommodation and are incapable of providing suitable accommodation for themselves. The Simon Community estimates that nationally there are currently at least 4,176 adults and 1,405 children experiencing homelessness, according to the statutory definition. Despite this little is formally known about the extent of the problem and certainly about its relationship to mental illness. Homeless people with mental health problems are exposed to all the same difficulties that other homeless people encounter but have more trouble meeting their needs because of their mental health condition. Estimates of the prevalence of severe disorder among the homeless in other countries range from 25%-50%. One Dublin study of hostel dwellers revealed that 52% suffered from depression, 50% from anxiety and 4% from other mental health problems2.

The document “A Vision for Change”3 recommended that a detailed understanding of the mental health needs and priorities of the population of homeless people should be gained. This would provide a guide as to how to allocate available resources in order to provide care which is relevant to the requirements of individual patients and their families. Around a quarter of those who die by suicide have had contact with the mental health services in the year before death4 and, given the high risk of suicidal behaviour in patients suffering from mental illness5,6, it is recommended that particular care be given to identifying service users most at risk in order to intervene with strategies that reduce the likelihood of proceeding to suicidal behaviour. The prevalence rates of suicide in the homeless population range from 1-3%7. According to the National Confidential Inquiry report7 in 2001, those homeless people who died by suicide had high rates of co-morbidity, alcohol and drug misuse and violence.

In the UK, around one third of those convicted of homicide between 1997 and 2006 had a diagnosis of mental disorder based on life history7. The majority had alcohol or drug dependence or personality disorder and most did not meet criteria for severe mental illness. 10% had been in contact with the mental health services in the year prior to the offence7. 3% of homicide perpetrators with mental illness were homeless7. According to the national homeless census which was carried out in 2008, 472 individuals availed of the homeless services in Cork City at the time of the survey8. Over 50 people currently attend the Mental Health Service for Homeless. One or more members of a multidisciplinary team provide input for patients depending on need. The purpose of the current study was to provide a detailed profile of service users attending the mental health services for homeless in Cork, including demographic and clinical data and, in particular, to focus on factors which are known to be associated with suicide and homicide. In addition, a comparison was made of the study group with service users of a local general adult mental health service.

Methods

With the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals, a retrospective case note review of all service users of the Mental Health Service for Homeless People in Cork City was carried out. Data regarding demographic details and diagnosis was collected. Factors known to be associated with increased risk and those which were common in people who died by suicide or committed homicide in the UK7 were also recorded. Similar data was gathered from the case notes of service users attending a Cork General Adult Mental Health Service. Graphpad Prism version 5 for windows9 was used for statistical analysis.

Results

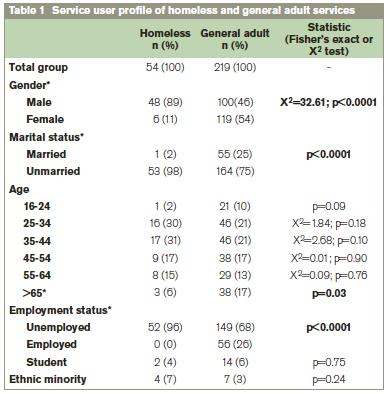

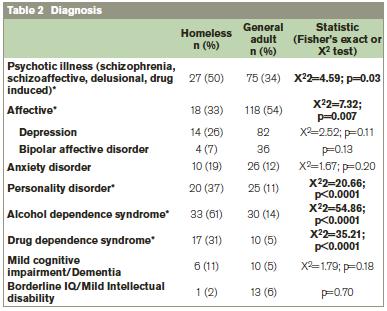

54 people were attending the Mental Health Service for Homeless in Cork City at the time of the study. Patient demographic profile and its comparison with those attending a local general adult service are outlined in Table 1. The homeless group were significantly more likely to be male (89% v 46%; p<0.0001), unmarried (98% v 75%; p<0.0001) and unemployed (96% v 68%; p<0.0001). They were also less likely than the general adult group to be over 65 years of age (6% v 17%; p=0.03). There was no difference between the two groups within other age groups. The diagnostic profile of studied service users is described in Table 2. There was a significantly higher prevalence of schizophreniform disorder (50% v 34%; p=0.03); personality disorder (37% v 11%; p<0.0001); alcohol (61% v 14%; p<0.0001) and drug dependence (31% v 5%); and a lower prevalence of affective disorders (33% v 54%; p=0.007) in the homeless service users, though there was no difference between groups in relation to either depression or bipolar affective disorder alone.

* indicates statistically significant difference between groups. The figures for “unemployed” refer to those not working outside the home.

* indicates statistically significant difference between groups. Note: some service users had more than one diagnosis.

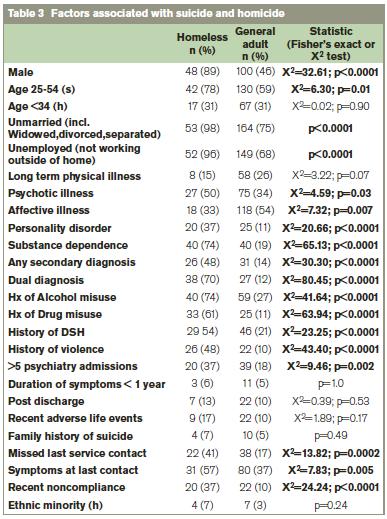

Factors known to be associated with increased risk and those which were common (i.e. present in over 10% of cases) in people who died by suicide or committed homicide in the UK7 are listed in Table. 3 along with their prevalence in the groups studied here. Of the 24 factors examined, the homeless group had a mean of 9 factors associated with suicide and similarly, homicide, this is in comparison with a mean of 6 factors in the general adult group (p< 0.0001). Homeless service users were more likely than those attending the general adult mental health services to have a history of deliberate self harm (54% v 21%; p<0.0001) and physical violence (48% v 10%; p<0.0001). The study group were also significantly more likely to have a history of alcohol (74% v 27%; p<0.0001) or drug (61% v 11%; p<0.0001) misuse (i.e. any mention of alcohol or drug misuse in the history not necessarily meeting criteria for dependence). There were higher levels of non compliance (37% v 10%; p<0.0001), missed appointments (41% v 17%; p=0.0002) and active symptoms (57% v 37%; p=0.005) in the homeless group but they also had significantly more input from multidisciplinary team members (74% v 37%, p<0.0001) and were seen more frequently by the psychiatrist (mean of 3.3 weekly v 10.4 weekly; p<0.0001).

(s) factor seen in suicide; (h) factor seen in homicide perpetrators7

Discussion

The profile emerging from this study draws attention to the complexity of this minority group of mental health service users. The homeless group were significantly more likely to be male, unemployed, unmarried and under 65 compared to their general adult counterparts or compared to adults in the general population of Cork. Levels of unemployment and lack of a marital relationship are high in those attending mental health services in general but were significantly higher again in the homeless group, highlighting the potential issues of social isolation and lack of occupation which may exacerbate or maintain symptoms and add to risk of relapse and suicide. There was a high prevalence of severe mental illness in the homeless population, with particularly high levels (50%) of schizophreniform illness in comparison to general adult mental health services. This is compounded by the especially high rates of dual diagnosis (70%), i.e. those suffering from both a mental health diagnosis and substance abuse, and almost half (48%) of the population studied suffering from a secondary mental health diagnosis, resulting overall in a particularly difficult group to treat.

In looking solely at twenty four features which have been seen in those who died by suicide or committed homicide, the group of homeless patients displayed many of these, with 39% having more than ten factors associated with homicide and 43% having more than ten factors associated with suicide compared to 8% and 9%, respectively, of those attending the general adult services. In addition to the high levels of complicated mental illness demonstrated by the high prevalence of severe symptoms, secondary diagnoses and dual diagnoses, this group also had higher numbers with more than five admissions to psychiatric inpatient units, had higher levels of active symptoms or symptoms at their last contact with the team and appear to be high risk. They were also more likely to be non compliant with treatment and required more intensive input from the multidisciplinary team. A limitation of this study was that data collected was based solely on case note records. It is possible that some details may not have been available leading to an underestimation in results such as presence of risk factors.

As detailed above, one of the motives for carrying out this study was to identify the needs of the homeless population attending mental health services. From the findings it is clear that, in addition to the physical and social needs of any homeless person with issues such as isolation and lack of occupation, this group have the additional burden of severe and complex mental illness, addiction and are at risk of suicide and possibly violence. Currently, this group is cared for by a mental health team consisting of a consultant psychiatrist part time, two community mental health nurses and a psychologist with no access to a mental health social worker or occupational therapist. It is essential that those most at risk are recognised and receive appropriate input form well resourced multidisciplinary teams to ensure there is intensive treatment of any underlying mental illness as well as dealing with addiction and social issues in order to reduce morbidity and risk.

Correspondence: E Dunne

Department of Psychiatry, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Government of Ireland (1988) Housing Act. Irish Statute Book.

2. Feeney A, McGee H, Holohan T, Shannon W. (2000) The Health of Hostel-Dwelling Men in Dublin: perceived health status, lifestyle and healthcare utilisation of homeless men in south inner city Dublin hostels. Department of General Practice & Health Services Research Centre, Department of Psychology, RCSI & Department of Public Health, Eastern Health Board. Available at epubs.rcsi.ie.

3. A Vision for Change. Department of Health and Children. (2006) available at www.dohc.ie/publications/vision_for_change.html

4. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, McDonnell R, Harris C, McCann K, Kiernan K, Davies S, Bickley H, Parsons R. Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey BMJ 1999; 318:1235-9

5. Morgan HG, Stanton R. Suicide among psychiatric inpatients in a changing clinical scene. British Journal of Psychiatry 1997; 171: 561-3

6. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, Patterson C. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-111-R axis 1 disorder: case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175, 175-9

7. Appleby L. Department of Health, UK. Safety First: Report of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness 2001 available at www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics

8. Homelessness: An Integrated Strategy 2009-2011 available at www.corkcity.ie

9. Graph Pad Prism version 5.0, Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA 10. Central statistics office 2006 census reports available at www.cso.ie/census/Census2006Results.html

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|