|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I Basit,SN Johnson,E Mocanu,M Geary,S Daly,M Wingfield

|

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2012 Mar;105(3):80-3

|

|

I Basit1, SN Johnson1, E Mocanu2, M Geary2, S Daly3, M Wingfield3

1Coombe Women and Infant’s University Hospital, Cork St, Dublin 8

2Rotunda Hospital, Parnell Square, Dublin 1

3National Maternity Hospital, Holles St, Dublin 2

Abstract

A retrospective audit was performed of all high order multiple pregnancies (HOMPs) delivered in three maternity hospitals in Dublin between 1999 and 2008. The mode of conception for each pregnancy was established with a view to determining means of reducing their incidence. A total of 101 HOMPs occurred, 93 triplet, 7 quadruplet and 1 quintuplet. Information regarding the mode of conception was available for 78 (81%) pregnancies. Twenty eight (27.7%) were spontaneous, 34 (33.7%) followedIVF/ICSI/FET treatment (in-vitro fertilisation, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, frozen embryo transfer), 16 (15.8%) resulted from Clomiphene Citrate treatment and 6 (6%) followed ovulation induction with gonadotrophins. Triplet and HOMPs are a major cause of maternal, feta land neonatal morbidity. Many are iatrogenic, arising from fertility treatments including Clomiphene. Reducing the numbers of embryos transferred will address IVF/ICSI/FET-related multiple pregnancy rates and this is currently happening in Ireland. Clomiphene and gonadotrophins should only be prescribed when appropriate resources are available to monitor patients adequately.

Introduction

High order multiple pregnancies (HOMPs) are a major cause of maternal, fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. There is an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm labour, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes and caesarean section. In 2002 in the United States, the mean age at delivery for twins was 35.3 weeks, 32.2 weeks for triplets, and 29.9 weeks for quadruplets as compared with 38.8 weeks for singletons.1 The decrease in mean gestational age at the time of delivery increases the risk of intraventricular haemorrhage, (IVH), necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and cerebral palsy (CP).2 Some studies postulate that at least 5% of all triplet pregnancies are jeopardized by life-threatening fetal complications in at least one of the fetuses3,4. Owing to their prematurity and low birth weight, multiples comprise a disproportionate portion of neonatal intensive care admissions10. Cerebral palsy (CP) has also been associated with multiple births. Children from a multiple pregnancy having a four times higher risk of developing CP compared with their singleton counterpart6. This risk is mostly related to the higher rates of prematurity.

The incidence of triplet pregnancies has risen steadily worldwide, primarily because of the development of assisted reproductive technology. The rate of triplets and other higher order births in the US increased from 29 per 100,000 live births in 1971 to 174 per 100,000 live births in 19977,9. These authors found that although the number of spontaneously conceived triplets increased slightly in the past 30 years, this only accounted for about 10% of the increase in multiple births. The rest was thought to be because of the introduction of ovulation-inducing drugs in the late 1960s and the advent of artificial reproductive technology (ART) in the 19807-9. A US study11 assessed the mode of conception of triplet and quadruplet pregnancies between 1998 and 2003 and found that the estimated percentages of multiple births due to ART and OI were twins 16% and 21%, triplets 45% and 37%, and quadruplets 30% and 62%, respectively.

A UK study12 in 2003 evaluated the mode of conception, multiplicity of pregnancy, and the outcome in all UK hospitals during one calendar week. Data was received from 178 maternity units (72.7%) on 6,913 deliveries. Of all pregnancies, 6,638 (96%) (including the only triplet) were conceived spontaneously and 133 (1.9%) with assistance. The multiple pregnancy rate was significantly greater in assisted (13.5%) than in spontaneous (1.2%) conceptions. No data exist regarding the mode of conception of twins and HOMPs in Ireland. The aim of this study was to evaluate the mode of conception of triplet and higher order multiple pregnancies in three Dublin teaching hospitals.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of all HOM deliveries in the three maternity teaching hospitals in Dublin (Rotunda Hospital, Coombe Women and Infant’s University Hospital and National Maternity Hospital) for a period of 10 years (1999-2008). Women who delivered triplets or higher order multiple pregnancies were identified from each hospital’s annual reports. The mother and infant charts were retrieved for all of these cases and data relating to mode of conception was extracted from the GP or other referral letter and the antenatal history section of both mother’s and infants’ charts. If the mode of conception was not detailed in the chart the case was classified as “mode of conception unknown”. The data was analysed on a Microsoft Excel programme.

Results

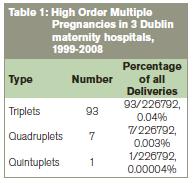

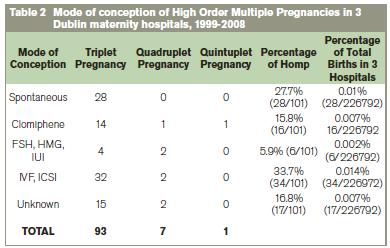

A total of 101 mothers delivered 312 babies in the 10 year period. Ninety three triplet, 7 quadruplet and 1 quintuplet pregnancies occurred, representing respectively 0.04%, 0.003% and 0.0004% of total births (226,792) at the 3 hospitals. Information regarding the mode of conception was available for 84 (83.1%) pregnancies. Of total HOMPs(N=101) 28 (27.7%) were spontaneous, 16 (15.8%) resulted from Clomiphene Citrate treatment, 6 (5.9%) followed gonadotrophin ± IUI therapy and 34 (33.7%) resulted from IVF/ICSI/FET treatment. The source of the pregnancy was unknown or not documented 17 (16.8%). Of those treated with IVF/ICSI/FET, 2 embryos were transferred in 8 cases (23.5%), 3 in 15 cases (44.1%), and the number transferred was not recorded in 11 (32.4%) cases. The mode of delivery of these pregnancies was vaginal delivery n=6 (5.9%), elective Caesarean Section (CS) n=70 (69.3%) and emergency CS n=25 (24.7%).

Figure 1: Graphic representation of percentages of mode of conception of HOMPs.

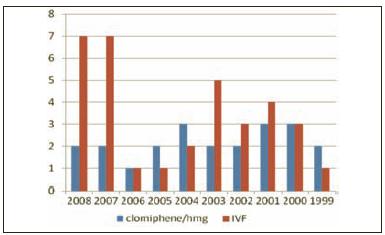

The incidence of HOMP pregnancies resulting from IVF and clomiphene citrate treatments was documented for each year of the study to analyse possible treatment trends. The no. of HOMP pregnancies resulting from Clomiphene treatment remained steady throughout the study period, averaging 2-3 pregnancies per annum. The no of HOMP pregnancy resulting from IVF/ICSI/FET rose to 2003 and then seemed to decline, but unfortunately rose again in 2007 and 2008.

Figure 2: Trends of treatment of IVF and Clomiphene/HMG during the study period.

Discussion

The occurrence of HOMPs varies worldwide. The main aetiological factors are maternal age, parity, racial background and fertility treatments such as ovarian stimulation with clomiphene or gonadotrophins and assisted reproductive techniques such as in-vitro fertilisation.13 A Canadian study, Collins et al in 2007, shows that multiple birth rates began to decline worldwide in the 1950s, reaching a minimum in the 1970s and rising since then. Both twin and triplet rates followed the same rising trend until 1998, after which triplet birth rates began to decline while twin birth rates continued to rise. Rising maternal age is associated with a rising frequency of dizygotic twinning up to 37 years of age. Older maternal age, associated with the social trend to delayed child bearing, accounts for 25- 30% of the rise in multiple birth rates globally since 1970. The resulting rise in the prevalence of infertility has given rise to unprecedented use of ovarian stimulation treatments that stimulate the development of multiple oocytes. ART and ovulation stimulation with clomiphene citrate or gonadotrophins without assisted reproduction accounted for similar proportions of both twin births (20- 30%) and triplet births (30- 40%) worldwide. The fall in triplet rates since 2000 is reassuring, but fetal reduction of high order pregnancies may be a factor in falling triplet and rising twin rates. Continuing attention is therefore needed to ensure all possible means of minimizing triplet and higher order multiple pregnancies13.

In our study 34 sets of triplets resulted from IVF treatment. Of these, there were 2 embryos transferred in 8 cases and 3 embryos transferred in 15 cases. Information regarding the number of embryos transferred in the remainder is not available but it is likely to have been at least 3 in the majority of cases. Over the last number of years major progress has been made internationally in terms of reducing the multiple pregnancy rate associated with IVF. For many years, the norm worldwide has been to transfer two embryos with only 21% of cycles in Europe in 2005 involving the transfer of three embryos14. While this significantly reduces triplet and higher order multiple pregnancies, the incidence of twins is still unacceptably high. The most recent European figures show that in 2005, 78.2% of IVF babies born were singleton, 21% were twins, 0.8% were triplets14.

Elective single embryo transfer (eSET) has been advocated in IVF, particularly where the overall prognosis for pregnancy is thought to be good. Elective single embryo transfer provides clear potential for reducing multiple pregnancy rates. This approach has been pioneered in Scandinavia, particularly Finland and Sweden, and subsequently in other European countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands15-21. By employing an eSET policy, many clinics in Finland have reduced their twin pregnancy rate to less than 10%19,21,22. Authoritative bodies in other countries have called for strategies to reduce the multiple pregnancy rates that follow assisted conception. In 2006, the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) commissioned an expert party report entitled “One Child at a Time: Reducing Multiple Births after IVF”23. In 2008, the British Fertility Society, in conjunction with the UK Association of Clinical Embryologists, introduced guidelines for eSET in the UK with the aim of reducing the multiple pregnancy rate associated with IVF to less than 10%.24 Currently no national guidelines exist in Ireland regarding the number of embryos for transfer. However, many Irish ART clinics are now advocating eSET in appropriate couples and encouraging results have been reported.25

Some of the women who conceived triplets following IVF in our group had their IVF abroad and conceived using donor oocytes. Unfortunately this information was not available for the majority of cases. In treatments involving donor oocytes, the age of the woman donating the oocytes should be used in determining how many embryos are transferred. Sadly in some countries, triple embryo transfer is advocated even if the donor of the oocytes is young. An older recipient patient is thus at greatly increased risk of high order multiple pregnancy. While Irish clinics have no control over what occurs in other jurisdictions, Irish couples contemplating treatment abroad, particularly with donor oocytes, should be advised to limit the number of embryos transferred to one or two. Of the HOMPs in this study, 22 cases were due to ovulation induction, 16 with Clomiphene and 6 with FSH/HMG/IUI. Clomiphene contributed 14 sets of triplets, 1 set of quadruplets and one set of quintuplets. FSH /HMG contributed 4 sets of triplets and 2 of quadruplets. These quadruplet and quintuplet pregnancies are particularly worrying. Ovulation induction is a well recognised major cause of HOMP.

A recent study in Dublin (Couglan et al8)showed that of 182 women receiving very low dose (25-50 mgs) of clomiphene, regular ultrasound showed 14% had three and more follicles developing even with this small dose. In this study total of forty-six cycles resulted in pregnancy. The cycles in which three follicles had been identified resulted in two pregnancies (4.3%). Of these 46 pregnancies, 2 were twins and 1 was a triplet pregnancy. According to the UK NICE guidelines, women undergoing treatment with clomiphene citrate should be offered ultrasound monitoring during at least the first cycle of treatment to ensure that they receive a dose that minimises the risk of multiple pregnancy. The Dublin study supports this, as does this current study.

The incidence of spontaneous triplet pregnancies in our study (30%- 28/93) is slightly higher than that found in a similar US study11(18%). It is disappointing that the mode of conception was not known for 15 (16.8%) of our cases. This is because this was a retrospective study based on review of hospital notes and the mode of conception was not documented in 16.9% of charts. This may be partly due to the fact that, in Ireland, an unfortunate stigma surrounds fertility treatment for some couples and they may not have been keen to inform caregivers of the mode of conception. This would have been particularly so in the earlier years of this study and may also have influenced the number of cases recorded as “spontaneous” conceptions. It is likely that at least some of the unknown cases resulted from fertility treatment so our figures if anything under-estimate the risk of multiple pregnancy following fertility treatment. In conclusion ART and ovulation induction are a major cause of HOMP in Dublin. These are high risk pregnancies and their incidence must be reduced. It is imperative that elective single embryo transfer be encouraged and triple embryo transfer discouraged. Clomiphene citrate and gonadotrophins should only be used in the lowest effective dose possible and when there are adequate facilities and expertise available to ensure ultrasound scanning with cancellation of treatment when multiple follicles develop.

Correspondence: I Basit

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Coombe Women and Infant’s University Hospital, Cork St, Dublin 8

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Hruby E, Sassi L, Gˆrbe E, Hupuczi P, Papp Z. [The maternal and fetal outcome of 122 triplet pregnancies] Orv Hetil. 2007 Dec 9;148: 2315-28.

2. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al: Births final data 2002. National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 42, No. 10, Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2003.

3. Borlum KG. Third-trimester fetal death in triplet pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:6-9.

4. Gonen R, Heyman E, Asztalos E, Milligan JE. The outcome of triplet gestations complicated by fetal death. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:175-178.

5. Rydhstroem H, Heraib F: Gestational duration, and fetal and infant mortality for twins vs singletons. Twin Res 2001; 4:227.

6. Topp M, Huusom LD, Langhoff Roos J, et al: Multiple birth and cerebral palsy in Europe: a multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004; 83:548.

7. Cunningham FC, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, Leveno J, Gilstrap K, editors. Multiple pregnancies. In: Williams Obstetrics. 19th ed. Norwalk: Appleton and Lange; 1993: 891-918.

8. Couglan C, Fitzgerald J, Milne P, Wingfield M. Is it safe to prescribe Clomifene Citrate without ultrasound monitoring facilities? J obstet Gynaecol 2010; 30:393-6.

9. Botting BJ, Davies IM, Macfarlane AJ. Recent trends in the incidence of multiple births and associated mortality. Arch Dis Child 1987;62:941-950.

10. Donovan EF, Ehrenkrang RA, Shankaran S, et al: Outcomes of very low birth weight twins cared for in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network's intensive care units. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179:742.

11. Dickey Rp, Taylor SN, Lu Py: Risk factors for high-order multiple pregnancy and multiple birth after… Fert Steril. 2007 Dec;88:1554-61

12. Bardis N, Maruthini D, Balen AH. Modes of conception and multiple pregnancy: a national survey of babies born during one week in 2003 in the United Kingdom: Fertil Steril. 2005 Dec;84: 1727-32.

13. Collins J. Global epidemiology of multiple birth: Reprod Biomed Online. 2007; 15 Suppl 3:45-52.

14. Nyboe Andersen A, Goossens V, Bhattacharya S, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and intrauterine inseminations in Europe, 2005: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2009; 1:1-21.

15. Gerris J, De Neubourg D, Mangelschots K, Van Royen E, Van de Meerssche M, Valkenburg M. Prevention of twin pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection based on strict embryo criteria: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Hum Reprod 1999; 4: 2581-7.

16. Martikainen H, Tiitinen A, Tomas C, et al. One versus two embryo transfer after IVF and ICSI: a randomized study. Hum Reprod 1990; 16: 1900-3.

17. Lukassen HG, Braat DD, Wetzels AM, et al. Two cycles with single embryo transfer versus one cycle with double embryo transfer: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2005; 20: 702-8.

18. Thurin A, Hausken J, Hillensjo T, et al. Elective single embryo transfer versus double embryo transfer in in-vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2392-402.

19. Tiitinen A, Unkila-Kalllio L, Halttunen M, Hyden-Granskog C. Impact of elective single embryo transfer on the twin pregnancy rate. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 1449-53.

20. Veleva Z, Vilska S, Hyden-Granskog C, Tiitinen A, Tapanainen J S, Martikainen H. Elective single embryo transfer in women aged 36-39 years. Hum Reprod 2006; 21: 2098-102.

21. Martikainen H, Orava M, Lakkakorpi J, Tuomivaara L. Day 2 elective single embryo transfer in clinical practice: better outcome in ICSI cycles. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 1364-6.

22. Soderstrom-Anttila V, Vilska S, Makinen S, Foudila T, Suikkari AM. Elective single embryo transfer yields good delivery rates in oocyte donation. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 1858-63.

23. Braude, P. One child at a time: Reducing multiple births after IVF. HFEA 2006.

24. Cutting R, Morroll D, Roberts S A, Pickering S, Rutherford A. Elective Single Embryo Transfer: Guidelines for Practice British Fertility Society and Association of Clinical Embryologists. Human Fertility 2008; 11: 131-146.

25. P Milne, E Costello, C Allen, H Spillane, J Vassello, M Wingfield. Reducing Twin Pregnancy rates after IVF- elective single embryo transfer eSET, Irish Medical Journal January 2010; 103.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|