|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E Flynn,A Flavin

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2012 Mar;105(3):89-91

E Flynn, A Flavin

Western Regional General Practice Training Programme, Co Galway

Abstract

ABPM is an invaluable clinical tool, as it has been shown to improve blood pressure control in Primary Care. Many clinical guidelines for hypertension advocate ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. This study aims to quantify the use of clinical guidelines for hypertension and to explore the role of ABPM in Primary Care. A questionnaire survey was sent to GPs working in the West of Ireland. 88% (n=139) of GPs use clinical guidelines that recommend the use of ABPM. 82% (n=130) of GPs find use of clinic blood pressure monitoring insufficient for the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension. Despite good access to ABPM, GPs report lack of remuneration, 72% (n=116), cost 68% (n=108), and lack of time, 51% (n=83) as the main limiting factors to use of ABPM. GPs recognise the clinical value of ABPM, but this study identifies definite barriers to the use of ABPM in Primary Care.

|

|

Introduction

Uncontrolled hypertension is a major cause of stroke and cognitive impairment and is the single most important risk contributing to 60% of all cardiovascular deaths1-3. In Ireland, high blood pressure affects 70% of those aged 70 years and over4. Apart from the life changing effects of the illness on the individual, uncontrolled hypertension poses a significant burden on health services5,6. In addition, the burden of hypertension is set to increase in an aging population in Ireland7. General practice is the cornerstone for screening, diagnosis and management of hypertension and its ill effects. International research in this area has yielded practice-changing clinical guidelines, many of which recommend the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)8-11. Most recently, in February 2011, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published a draft of it’s guideline for the Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension which recommends ABPM for routine diagnosis of hypertension in Primary Care8. A prominent Irish study has shown that ABPM significantly improves blood pressure control in primary care12. European work in this area has revealed circadian rhythm abnormalities on ABPM that are related to increased cardiovascular events and strokes13-15. ABPM is the gold standard for diagnosis of hypertension, provides a clearer picture of blood pressure and can reveal cases of white coat and masked hypertension8-16.

In Ireland there is currently no evidence quantifying the use of clinical guidelines for hypertension in Primary Care. This merits of ABPM are well described8-16. This study aims to quantify the use of clinical guidelines for hypertension and identify the role of ABPM in General Practice and barriers to it’s use.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional quantitative study. A postal questionnaire was designed and piloted initially to ten GPs and modified accordingly. The final questionnaire was then sent to all 240 GPs registered for General Medical Services in counties Galway, Roscommon and Mayo in September 2010. A short covering letter explaining the purpose of the study was included with a stamped addressed envelope for the reply. The principles of increasing response rates to postal questionnaires were applied17. Participation was voluntary and all responses were anonymous. The questionnaire sought information about demographic details, use of clinical guidelines for hypertension, which guidelines were used, opinion of clinic blood pressure monitoring (CBPM) compared to ABPM, access, indications and limitations to use of ABPM. In total the questionnaire consisted of 12 questions with a tick-box answer format. Included with the tick-box questions were free text sections for questions relating to which clinical guidelines are used, reported use of ABPM and reported limitations to use of ABPM. Results were analysed using Epi Info, version 3.5.1. The Chair of the Research Ethics Committee of the Irish College of General Practitioners ruled that this study did not require formal ethical approval, as this study does not involve any access to patients or patient data and only involved a questionnaire survey of healthcare workers who are not identifiable.

Results

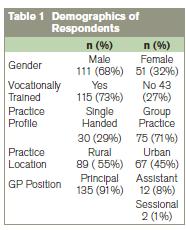

The response rate was 68% (n=162). Table 1 illustrates the demographics of the respondents. 88% (n=139) of GPs use clinical guidelines for hypertension. The British Hypertension Society Guidelines (BHS) for the Management of Hypertension 2004was reported as the most commonly used [60% (n=83)] and the European Society for Cardiology/European Society for Hypertension 2007 Guidelines was reported as being used by 36% (n=50) of GPs. Least commonly used by 4% (n=5) was the 2003 World Health Organisation (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) Guidelines for Hypertension. These three clinical guidelines advocate the use of ABPM for the investigation of hypertension for certain indications.

82% (n=130) of GPs were of the opinion that the use of clinic sphygmomanometer only is insufficient for the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension. 89% (n=141) of GPs have access to ABPM. Within this group, 89% (n=126) can access this form of monitoring within their own surgery and 11% (n=15) source it outside of the surgery, from a local hospital or neighbouring practice. Of those who do not have access to ABPM, 28% (n=5) believe that use of clinics phygmanometer alone is sufficient for diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension. Within the group that has access to ABPM, 83% (n=117) stated that use of clinics phygamanometer alone is not enough for diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension.

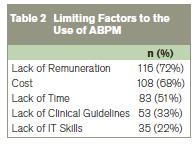

White-coat hypertension is reported as the most common clinical indication for use of ABPM [84% (n=136)]. 73% (n=118) used ABPM to investigate uncontrolled hypertension, and57% (n=90) choose the use of ABPM in newly diagnosed cases of hypertension. 46% (n=75) used ABPM to monitor response to antihypertensive treatment. Other indications reported by GPs include investigation of suspected cases of hypertension, hypertension in pregnancy and convincing the patient of having a diagnosis of hypertension. Table 2 shows the factors that were considered a limitation to the use of ABPM. 74% (n=104) of GPs who have access to ABPM, cite lack of remuneration as the main reason for its lack of use. 89% (n=16) of GPs who don’t have any access to ABPM, cite cost as being a limiting factor for use of ABPM.

Discussion

This study shows that most GPs use clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hypertension. The two sets of guidelines used most frequently both advocate the use of ABPM9,10. This study shows that GPs recognise the clinical benefit of ABPM, as 82% (n=130) of GPs finding use of CBPM alone is insufficient for the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension. Most GPs have good access to ABPM in either their own surgery or elsewhere. Their use of ABPM correlates with clinical guideline recommendations. However despite this, this study identifies definite limitations to the use of ABPM in Primary Care today. Lack of remuneration, cost and lack of time are the main barriers for the use of ABPM within the patient population in this study. Understandably these are practical limitations and have a direct relationship to each other.

Since carrying out this study, NICE have published a draft for consultation of it’s 2011 guideline for the Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension8. This NICE guideline now recommends ABPM for routine diagnosis of hypertension in Primary Care. Also NICE now state that use of CBPM alone for diagnosis of hypertension leads to inaccurate diagnosis and will result in initiation of drug treatment for a significant number of patients who are actually normotensive. For these new guidelines, NICE have carried out the largest cost-benefit analysis of ABPM and this showed clearly that use of ABPM would result in substantial savings for the NHS. Previously, it has been shown that use of ABPM reduces treatment cost by 14% and results in fewer anti hypertensives being prescribed12,18. Medication costs are one of the biggest expenses directly related to hypertension. ABPM use is now approved and remunerated by Medicare and Medicaid in the US19. Given the clinical importance of ABPM, the Health Service Executive should formally recognise the clinical and the economical benefit of ABPM in Primary Care and offer appropriate remuneration to GPs in Ireland for it’s use in practice.

This study does have some limitations. Firstly, questionnaire surveys may not accurately reflect what actually happens in practice. Secondly the study only examined one area in Ireland. The current practice in different regions may differ. However given the response rate, the number of practices surveyed and the equal response rate from rural and urban practices, the findings of this study are likely to reflect the use of ABPM throughout the country. Hypertension is a serious health concern. ABPM is an invaluable clinical tool in Primary Care. However definite barriers exist limiting the use of ABPM. Incentivizing the use of ABPM in Primary Care would increase the use of this form of monitoring, effectively tackle the growing problem of hypertension and in turn, have positive economic effects.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all General Practitioners who participated in this study and support from the General Practice Postgraduate Department at National University Institute of Galway.

Correspondence: E Flynn

Western Regional Training Programme, Pinegrove Medical Centre, Mountbellew, Co Galway

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Anon. Hypertension: Uncontrolled and Conquering the World. Lancet 2007; 370: 539

2. O’Brien E. Dipping Comes of Age: The Importance of Nocturnal Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2009; 53; 446-447.

3. Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, Thijs L et al. Risks of Untreated and Treated Isolated Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly: Meta-analysis of Outcome Trials. Lancet.2000; 355: 865–872.

4. O’Brien E. Cardiovascular mortality: Affluent Ireland faring badly in comparison to other European countries. Mod Medicine 2008; July31-32

5. Cost of Stroke in Ireland: Estimating the Annual Economic Cost of Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA) in Ireland, Irish Heart Foundation Cost September 2010

6. Truelsen T, Ekman M, Boysen G. Cost of Stroke in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005; 12: 78-84.

7. Castelino R, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Targeting Suboptimal Prescribing in the Elderly: a Review of the Impact of Pharmacy Services. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43: 1096-1106

8. Hypertension: Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults. NICE Guideline Draft for Consultation, February2011. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk

9. Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JP, Sever PS and Thom S McG; The BHS Guidelines Working Party Guidelines for Management of Hypertension: Report of the Fourth Working Party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004 - BHS IV. J Human Hypertens 2004; 18: 139-185

10. 2007Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 1462 – 1536

11. 2003 World Health Organisation (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) Statementon the Management of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003Nov; 21:1983-1992

12. Uallachain GN, Murphy G, Avalos G. The RAMBLER Study: The Role of Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement in Routine Clinical Practice: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ir Med J 2006; 99: 276-9

13. Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L et al. Superiority of Ambulatory Over Clinic Blood Pressure Measurement in Predicting Mortality: The Dublin Outcome Study. Hypertension 2005; 46: 156-161

14. Gorostidi M, Sobrino J, Segura J et al on behalf of the Spanish Society of Hypertension ABPM Registry investigators. Ambulatory blood pressure Monitoring in Hypertensive Patients with High Cardiovascular Risk: a Cross-Sectional Analysis of a 20000-PatientDatabase in Spain. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 977-984

15. O’Brien E. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement: the Case for Implementation in Primary Care. Hypertension. 2008; 51;1435-1441

16. O’Brien E, Twenty-four-hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement in Clinical Practice and Research: a Critical Review of a Technique in Need of Implementation. J Intern Med 2011; 10.1111 1365-2796

17. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Increasing Response Rates to Postal Questionnaires: Systemic Review. BMJ2002; 324: 1183-1185

18. Krakoff LR. Cost-Effectiveness of Ambulatory BP: A Reanalysis. Hypertension. 2006; 47: 29-34

19. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual Chapter 1, Part 1 (Sections 10 – 80.12) Coverage Determinations. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|