|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F McNicholas,N O'Connor,G Bandyopadhyay,P Doyle,A O'Donovan,M Belton

|

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2011 Apr;104(4):105-8

|

|

F McNicholas, N O'Connor, G Bandyopadhyay, P Doyle, A O' Donovan, M Belton

Lucena Clinic, 59 Orwell Rd, Rathgar, Dublin 6

Abstract

Children in care in Ireland have increased by 27% in the last decade. This population is recognized to be among the most vulnerable. This study aims to describe their placement histories, service use and mental health needs. Data was obtained on 174 children (56.5% of eligible sample) with a mean age of 10.83 (SD = 5.04). 114 (65.5%) were in care for three years or more. 29 (16.7%) did not have a SW and 49 (37.7%) had no GP. 50 (28.7%) were attending CAMHS. Long term care, frequent placement changes and residential setting were significantly related with poorer outcomes and increased MH contact. Given the increase in numbers in care and the overall decrease in resource allocation to health and social care, individual care planning and prioritizing of resources are essential.

Introduction

The term ‘looked after’ was introduced by the Department of Health, UK (1989) to describe all children in public care. In November 2009 there were 5,694 children in the care of the HSE (0.5% of the total child population)1, representing a 4% increase between 2007-2009. Most of the children (85%) are looked after in foster care and half reside in the Dublin region. A national UK survey found that 45% of children had mental health problems, representing a four fold increase in risk when compared to all children2 and experience significant health and educational inequalities throughout childhood.3 The increased vulnerability of looked after children, coupled with the increasing numbers in the care of the State, highlight the need to understand more fully from an Irish perspective who these children are and what is their current level of service use. The recent realisation that a significant number of children in care experienced premature death makes a study of this vulnerable group of children a major public priority. The aim of this study is to describe the placement histories, service use and mental health needs of children in care within two Dublin catchment areas.

Methods

Following ethical approval, Social Work Team leaders from two Dublin CAMHS catchment areas (one in South Dublin and one in North Dublin) were contacted. Consenting SW’s completed a study specific questionnaire relating to children within their care system. This included the age of the child, duration in care, reasons for entry into care, family history, and educational attainment. Information on the child’s service use, including allocation of a SW & GP and attendance at CAMHS was also collected.

Results

Data was obtained on 174 of the 308 children in care residing within the study catchment area (56.5% total eligible sample).

Demographics of Looked After Children

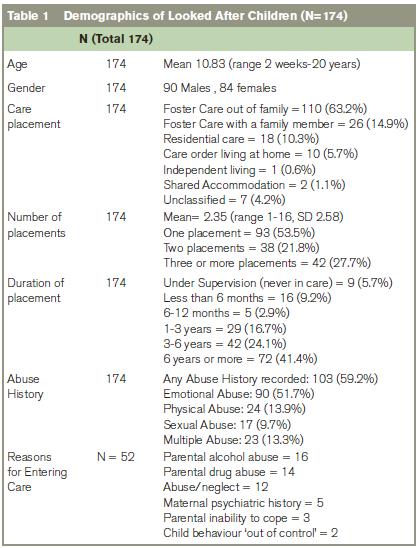

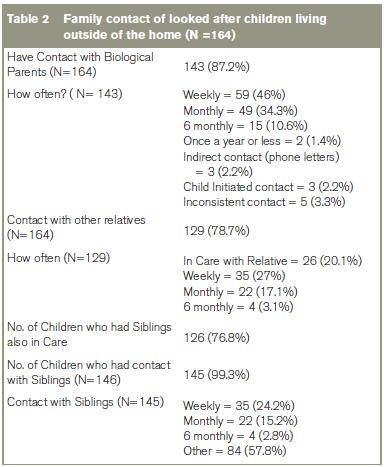

Information was received on 90 (51.8%) males and 84 (48.2%) females, with a mean age of 10.83 (SD = 5.04). The majority were in foster care (N=136, 78.2%), 26 (14.9%) being fostered by relatives. 18 children (10.3%) were in residential care, and 10 children (5.7%) at home under supervision orders. The mean number of out of home placements was 2.35 (SD=2.58, range 1-16). Two thirds were in care for three years or more (N=114, 65.5%). The majority of children had a history of abuse (N=103, 59.2%). The reason for entering care was given in 52 (30%) cases, with parental alcohol or drug misuse being a major factor (Table 1). Twenty-one children (12.8%) had no contact with their biological parents (Table 2).

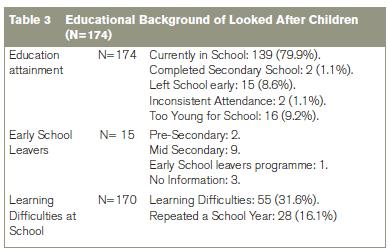

34 children (19.5%) had a family member with a mental health problem (depression or schizophrenia) and 35 (20.1%) had a family member who had a drug or alcohol related illness. Most of the children were currently attending school (139, 79.9%) but almost 10% had either left school early (15, 8.6%) or were inconsistent attendees (2, 1.1%) A third was considered to have learning difficulties (55/170, 32.4%) (Table 3).

145 (83.3%) of children in this study had an allocated social worker. 72.3% (125) had an identified GP and 48 (27.6%) were attending hospital services. A significant number of children had attended a child psychiatry assessment (61, 35.1%) or a psychological evaluation (59, 34.1%) as part of the child care planning, but a smaller number remained in ongoing contact with CAMHS (50, 28.7%), with males being over-represented (58%). The most common diagnosis cited was ADHD (11), Oppositional/Conduct disorder (11), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (4) and depression (3). Eleven children (6.3%) were prescribed medication, typically for ADHD. Sixteen children (19.3%) were noted to engage in self harming behaviour, typically cutting. Other services attended included counselling (43), probation (16) and substance abuse services (8).

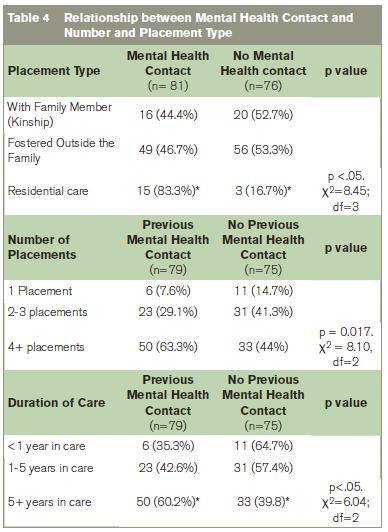

More than half of children in foster care were identified as having behavioural problems (59/110, 53.6%) increasing to 88.9% (16/18) for children in residential care, X2 (3, n =157) =16.19, p<0.05. Thirty-five (20.5%) children in the sample had displayed violent behaviour to residential care staff, foster carers or teachers. 74.3% of individuals who had displayed violent behaviour had a previous mental health contact. A history of offending behaviour was reported in 27 children (15.5%), the majority being male (20, 74%). Children with more frequent placements were more likely to have a mental health contact, X2 (3, n = 157) = 8.45, p<.05 (Table 4). Children in residential care were also more likely to have come into contact with MH services, X2 (3, n =157) =8.45, p<0.05) with 83.3% children in this group having had mental health contact. Fifty per cent of children in residential care were rated as having poor social interaction, compared to 21.9% of those in foster care, X2 (2, n = 149) = 17.40, p<0.05. While longer duration in care was associated with an increased likelihood of a MH contact, X2 (2, n = 154) = 6.04, p<.05, it was not linked with ongoing attendance, X2 (2, n = 83) = 3.62, p>0.05.

Discussion

Although information was received on just over half (56.5%) of the eligible sample, it portrays a picture of a vulnerable group of young children (mean age 10.83), in long term care (an average of 3 or more years in care) with multiple placement changes who experience significant psychological and educational morbidity. The majority of children (87.9%) in this study were in contact with their biological parents. The Child Care Act 19914 requires health boards to facilitate reasonable access between parents and children, supported by research suggesting more successful outcomes5. However, it is also recognized that inconsistent and stressful contacts can jeopardize the stability of a placement and the rights of parents and children need to be carefully balanced6,7. In the UK, due consideration is given to the rights of the child separate to the rights of the parent, a right that is not afforded to them in the Irish system due to the Irish Constitution, which protects the pivotal role and rights of parents. Children’s rights advocates are lobbying the Oireachtas for policy reform on this matter. Almost all the children in this study had siblings who were also in care (95.1%), yet only half (53.2%) were in a placement with their brother or sister. Although 92.9% had regular contact, given that placement with a sibling is known to enhance a child's outcome in terms of placement stability, development of relationships and enhanced coping skills.8

Despite their young age, 8.7% of children were early school leavers, and many had either learning difficulties or repeated a year in school, evidencing the fragmented educational provision experienced by many. This finding is in line with UK research which has shown that children in care have poorer academic achievement when compared with their peers9. Given the protective nature of educational attainment and positive relationships with teachers, careful educational planning must form a fundamental part of the child’s care plan.

It is recognised that looked after children often have greater difficulty accessing services. Alarmingly, only 83.8% of our sample had an allocated social worker and fewer (72.3%) had an identified GP. A recent report by the HIQA1 reported almost half of children in care had not been allocated a social worker by the HSE. The Ryan Report Implementation Plan aims to correct this deficit and invest €15 million to recruit an extra 270 social workers. Despite higher prevalence of mental health difficulties among children in care, only 28.7% were attending CAMHS. The reported disorders are similar to other studies investigating the prevalence of childhood psychiatric disorders among looked after children10,11. Further study is needed to understand the low attendance rate at MH services, which in other studies have been attributed to narrow CAMHS referral criteria, poor recognition by SW, referrers’ reluctance to pathologize children’s behaviour, mobility and engagement difficulties and general pessimism among SW in accessing mental health services12,13. Recent policy changes in the UK have led to the provision of funding for specialist mental health services. Given the success in other countries14, the implementation and evaluation of such teams in Ireland is warranted. While this may seem implausible given the current economic situation, the lack of financial input into general and mental health services for this very vulnerable group may result in increased personal, familial and economic costs later on. The positive benefits of early intervention with other medical disorders apply equally well to MH services for children in care.

Our study found an association between type, number and duration of placements and mental health. Children in residential care were significantly more likely to have contact with mental health services (83.3%) compared to children living either in foster care (46.7%) or with a family member (44.4%), consistent with other studies2,15,16. This may be attributable to different care experiences, selection effects or higher recognition by trained staff. Children placed in residential care are often very troubled children and have experienced frequent placement breakdowns. They may also be more likely to present with overt behavioral problem, as in our study (88.9% versus 53.5% in foster care) and increased socialization difficulties (50% versus 12.5%). The relationship between placement disruption and greater levels of mental health problems is complex because it is unclear as to whether mental health problems contribute to placement disruption or are a consequence of multiple placements. Researchers have found both cause and effect relationships17,18. Despite the study’s limitations of small sample size, low response rate and lack of child interview the authors feel it provides an informative and timely overview of children in care in the Dublin area.

In summary, looked after children frequently present with complex health and educational needs and often face many obstacles in accessing services. Contrary to Government recommendations, not all children are allocated an individual social worker or G.P and just over ¼ were in contact with CAMHS. In line with previous research, residential placement and number of placements both increased the likelihood of mental health contact. Given the poorer outcome for children in residential care, further research is needed to examine the factors associated with this type of placement. A comprehensive service which includes a dedicated social worker, GP, and specialist child psychiatry team would go along way to ensuring the continued and timely multi-disciplinary care that these young children deserve.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Colette McAndrew, Margaret Mitchell, Ceili O’ Callahan, Dr Brendan Doody and all the social workers who took the time to contribute towards this research.

Correspondence: F Mc Nicholas

Lucena Clinic, 59 Orwell Rd, Rathgar, Dublin 6

Email: [email protected]

References

1. The Health Information and Quality Authority. National Children in Care Inspection Report. HIQA, Dublin 2008.

2. Meltzer H, Corbin T, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford T. The mental health of young people looked after by local authorities in England: summary report. The Office for National Statistics, London, 2003.

3. Taussig H, Clyman R, Landsverk J. Children who return from foster care: A six-year prospective study of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics 2001; 108 :98-102

4. Department of Health. Child Care Act. Stationery Office, Dublin, 1991.

5. McAuley C, Davis T. (2009) The emotional well-Being of looked after children in England. Child Fam Soc Work 2009; 14:147-155.

6. Farmer E, Lipscombe J, Moyers S. Foster carer strain and its impact on parenting and placement outcomes for adolescents. Br. J. Soc. Work 2005; 35:237-253.

7. Sinclair I, Wilson K, Gibbs I. Foster Placements: Why They Succeed and Why They Fail, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 2005.

8. van Meeuwen A. Making family placements: working with risk and building on strengths. In Kemshall H and Pritchard J (eds), Good Practice in Risk Assessment and Risk Management. Gateshead: Athenaeum Press, 1997.

9. Mitic W, Rimer ML. The educational attainment of children in care in British Columbia. Child and Youth Care Forum 2002; 31:397-414.

10. Meltzer H, Lader D, Corbin T, Goodman, R, Ford T. The mental health of young people looked after by local authorities in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office, 2004.

11. Ford T, Vostanis P, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: a comparison with children living in private households. BJP 2007; 190:319–325.

12. Minnis H, Del Priore C. Mental health services for looked after children: implications from two studies. Adopt & Fost 2001, 25:27–38.

13. Callaghan J, Young B, Richards M, Vostanis P. Developing new mental health services for looked after children: a focus group study’. Adopt & Fost 2003; 27:51-63.

14. Philips J. Meeting the psychiatric needs of children in foster care: social workers' views. Psychiatr Bulletin 1997; 21:609-611.

15. Callaghan J, Young B, Pace F, Vostanis P. Evaluation of a new mental health service for looked after children. Clin Child Psychol and Psychiatr 2004; 9: 130-148.

16. Holtan A, Ronning J, Handegard B, Sourander A. A comparison of mental health problems in kinship and nonkinship foster care. Eur Child. Adolesc Psychiatr 2005; 14: 200-207.

17. Stanley N, Riordan D, Alaszewski H. The Mental Health of Looked After Children: Matching response to needs. Health Soc Care Commun 2005; 13:239-48.

18. Newton R, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse Neg 2000; 24:1363–1374

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|