Abstract

This study examined victimisation, substance misuse, relationships, sexual activity, mental health difficulties and suicidal behaviour among adolescents with sexual orientation concerns in comparison to those without such concerns. 1112 Irish students (mean age 14yrs) in 17 mixed-gender secondary schools completed a self-report questionnaire with standardised scales and measures of psychosocial difficulties. 58 students (5%) reported having concerns regarding their sexual orientation. Compared with their peers, they had higher levels of mental health difficulties and a markedly-increased prevalence of attempted suicide (29% vs. 2%), physical assault (40% vs. 8%), sexual assault (16% vs. 1%) and substance misuse. Almost all those (90%) with sexual orientation concerns reported having had sex compared to just 4% of their peers. These results highlight the significant difficulties associated with sexual orientation concerns in adolescents in Ireland. Early and targeted interventions are essential to address their needs.

Introduction

Identity issues are common in adolescence, including confusion over sexual orientation and sexuality 1,2. Increased rates of psychosocial difficulties, such as depression, anxiety and substance misuse have been reported amongst lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) young people,3-6 who more commonly report a history of having experienced child sexual abuse7. Given that each of these factors are recognised risk factors for suicidal behaviour, it is not surprising that young people in a sexual minority group have been shown to be at higher risk of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide8,9. Much of the research has been conducted in North America, with limited research in Europe10. A recent Irish study of 1,110 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender (LGBT) participants aged 14-73 years, found that, on average, they realised they were LGBT at 14 years of age but did not come out to others until age 2111. The years of concealed sexual orientation or gender identity coincided with particular mental health vulnerability and psychological distress11. This paper reports the findings of a cross-sectional school-based study of Irish adolescents. It aimed to examine the association between sexual orientation concerns, mental health difficulties and suicidal and risky behaviours.

Methods

Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) is a school-based health promotion and suicide prevention programme. It was implemented in 11 European countries and funded by the EU 7TH Framework Programme12. In Ireland, 17 randomly-selected, main-stream, mixed-gender secondary schools in Cork and Kerry participated. The parent(s)/guardian(s) of 1722 adolescents mostly in second year were asked to consent to their child participating in the project. A total of 1112 adolescents participated, representing a response rate of 65%. Students were aged 13-16 years and most were 14 years of age.

Participants completed a self-report questionnaire in the classroom setting. It included a range of internationally recognised scales: the Beck Depression Inventory; the Zung Self-Rated Anxiety Scale; the Paykel Suicide Scale; the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; the WHO Well-being Scale and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, pro-social behaviour). Students were also asked about victimisation, sexual assault, physical assault, alcohol, drugs and tobacco use, relationships and sexual activity. In Ireland, the students were also asked “have you had worries about your sexual orientation i.e. that you might be lesbian, gay or bisexual?” Those who answered positively to this question were compared with those who answered negatively in relation to a range of factors using Chi-square tests for categorical factors and one-way analysis of variance for continuous factors. The strength of the associations investigated by the Chi-square tests was assessed by the Phi statistic or Cramer’s V. In line with previous recommendations, associations were considered very weak if Phi or V < 0.10, weak if < 0.30, moderate if < 0.50 and strong if 0.50+. One-way analysis of variance was used rather than t-tests in order to directly measure effect size using partial Eta2 and, following established guidelines, the effect size was considered very small if partial Eta2 < 0.01, small if < 0.06, medium if < 0.14 and large if 0.14+.

Results

More than half of the 1112 students were male (600 (55.7%) male; 496 (45.3%) female), the vast majority were either 13 or 14 years of age (409 (37.5%) 13 years; 598 (54.8%) 14 years; 55 (5.0%) 15 years; 29 (2.7%) 16 years; Mean = 13.7 years) and over 80% lived with their mother and father (914; 83.4%). Of the 1079 who answered the question, 58 (5.4%, 95% confidence interval = 4.1-6.9%) indicated that they had concerns regarding their sexual orientation. This group consisted of 35 (60.3%) boys and 23 (39.7%) girls with a mean age of 14.1 years.

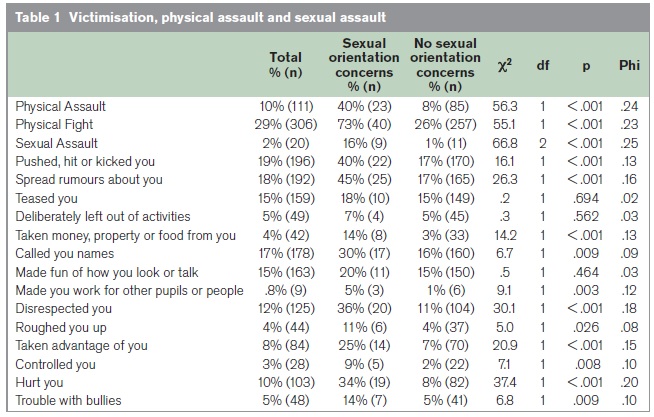

Note: Associations are considered very weak if Phi < 0.10, weak if < 0.30, moderate if < 0.50 and strong if 0.50+.

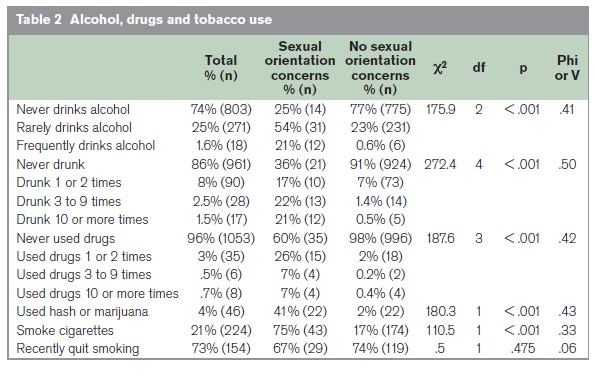

Note: Associations are considered very weak if Phi or V < 0.10, weak if < 0.30, moderate if < 0.50 and strong if 0.50+.

The young people who reported having concerns regarding their sexual orientation reported significantly increased levels of victimisation, especially regarding physical and sexual assault (Table 1). They were five times more likely to have been physically assaulted (40% vs. 8%) and one in six of them (16%) had been sexually assaulted compared with 1% of the adolescents with no sexual orientation concerns. Stronger associations were found regarding substance misuse (Table 2). One fifth of the adolescents with sexual orientation concerns drank alcohol frequently compared to 1% of the other young people. Only 36% had never been drunk compared with 91% of their peers. Three quarters of this group indicated that they were smokers compared with less than one fifth of their classmates. They were also much more likely to have used hash or marijuana (41% vs 2%).

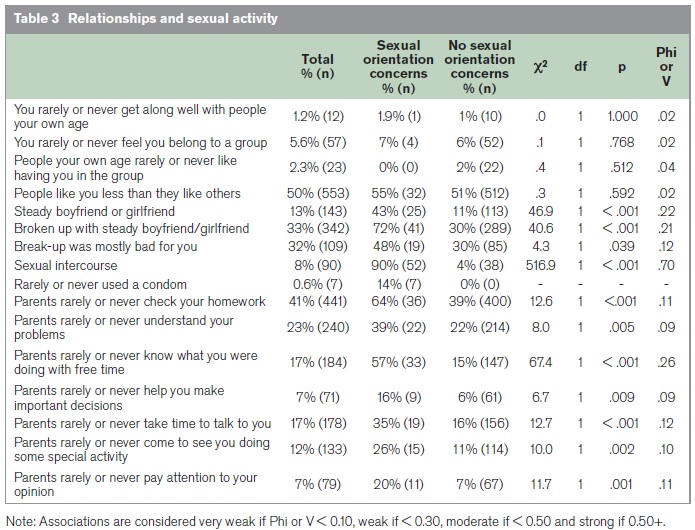

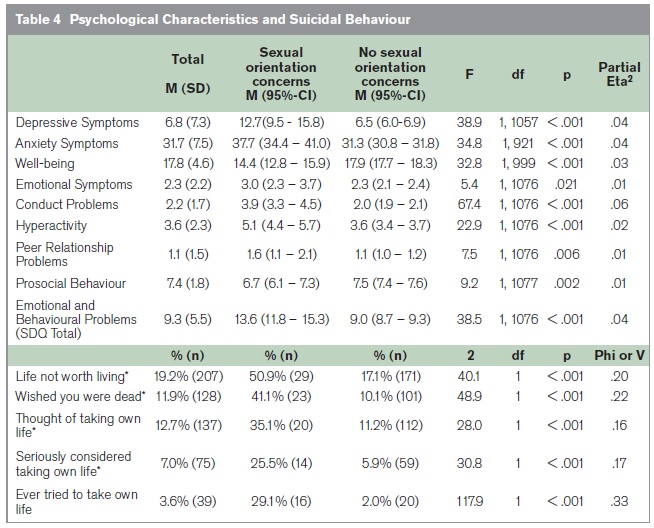

The students with sexual orientation concerns did not differ significantly from their classmates in terms of getting along with people their own age or feeling that they are liked and wanted in a group (Table 3). They were more likely to have had a steady romantic relationship (43% vs 11%) and to have experienced a break-up (72% vs 30%). The most marked difference related to sexual intercourse. Ninety percent of those with sexual orientation concerns reported having had sex compared to just 4% of their peers, they did not specify whether this was with same or opposite gender partners. In addition, the small number of young people who reported never or rarely using a condom when having sex were all among those with concerns about their sexual orientation. For each of seven measures, the young people with concerns about their sexual orientation more often reported a lack of parental attention, involvement and supervision (Table 3). Most (57%) of the group reported that their parents rarely or never know what they are doing with their spare time compared with 15% of their peers. The group with sexuality concerns had higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, emotional and behavioural problems, suicidal behaviour and lower levels of well-being (Table 4). The association was most evident with attempted suicide - 29% of these students having tried to take their own life compared to just 2% of the students without sexual orientation concerns.

Note: The effect size is very small if partial Eta2 < 0.01, small if < 0.06, medium if < 0.14 and large if 0.14+. Associations are considered very weak if Phi or V < 0.10, weak if < 0.30, moderate if < 0.50 and strong if 0.50+. * relates to the past two weeks

Discussion

This is the first Irish school-based study to show that adolescents with concerns regarding their sexual orientation experience significantly higher levels of victimisation and psychosocial difficulties. A major indicator of the level of their difficulties was the high prevalence of attempted suicide. Their high levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties as well as depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and suicidal behaviour and low levels of wellbeing are consistent with other studies3,4,8,9,13. The cross-sectional nature of the data means that causation cannot be inferred. Therefore, the findings could be interpreted as suggesting that students with high levels of victimisation and psychosocial difficulties are more likely to have concerns about their sexuality. These difficulties may induce uncertainty regarding sexual identity. For instance, abuse and dysfunctional backgrounds are known to adversely affect identity formation, of which sexual identity is one facet1-3. Alternatively, it is possible that these difficulties arise as a result of being a young person with concerns regarding sexual orientation. This may be particularly true in Ireland, given its strong identification with Catholicism, which views homosexual acts as sinful14. Moreover, male homosexuality was only decriminalised in Ireland in 1993.

The degree to which LGBT people have been alienated in all aspects of Irish life and culture has been well-documented11. Stigmatisation and internalised homophobia have been identified as other factors contributing to negative health outcomes amongst lesbian and gay adolescents15,16. Therefore, it is likely that some of the adverse experiences identified in this study are associated with being an LGB youth in Ireland. These include the high levels of victimisation, sexual and physical assault, substance abuse and risky sexual behaviour found in the current sample, all of which corroborate previous findings from other countries5-7,17,18. This may be compounded by the low levels of parental attention reported by this group. Positive parental attention is associated with better psychological well-being and reduced substance abuse amongst adolescents19,20. Despite the high levels of victimisation and bullying reported by this group, they did not differ from their classmates in terms of getting along well with others, feeling like they belonged to a group and the extent to which others liked having them in the group. This suggests that the high levels of peer relationship problems reported by these young people are due to interactions with peers outside their circle of friends.

This study supports the view that some young people become concerned about their sexual orientation at a young age. Previous research has indicated that most sexual-minority young people disclose their sexual identity towards the end of their secondary school years21. This happens even later among Irish LGBT people11. These years of concealed sexual orientation or gender identity coincided with psychological vulnerability and distress. Therefore, the current findings support the need for an environment that facilitates adolescents’ free expression of their sexual orientation concerns. In light of these findings, it is important to mention this study’s limitations. Although, participants were randomly selected without reference to sexual orientation, which is a strength of the study, the group with sexual orientation concerns was small. This precluded the use of more complex statistics to explore heterogeneity in the sample. This study collected self-report data, in a classroom setting. Therefore, as previously shown22, reporting may have been inaccurate for some sensitive questions. The phrasing of the key question (have you had worries about your sexual orientation i.e. that you might be lesbian, gay or bisexual?), could be seen as problematic. This could be viewed as self-exploration rather than a measure of sexual identity. LGB young people who were not worried about their sexual orientation may not have answered this question positively. Future studies should include multiple dimensions of sexual orientation23 in single as well as mixed gender schools, across different time periods, with a focus on protective factors24. Future studies could also examine whether the identified sexual experiences occur with same or opposite gender partners and also look at rates of attendance at mental health services e.g. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, as an indication of the severity of the identified difficulties.

Reach Out, the Irish National Strategy for Action on Suicide Prevention25 identifies LGBT people as a marginalised group and, as such, highlights the need to develop specific supports for them. At a preventative level, school and community-based health awareness programmes should include topics on sexuality and sexual orientation. The aim should be to inform young people with worries about these issues and reduce the level of stigmatisation and victimisation. These interventions should also be sensitive to the cultural contexts of LGBT young people. Key elements that should be addressed include the development of healthy sexual identities and helping young people to disclose their sexual identity to peers and adults. It is possible that adolescents with sexual orientation concerns are in need of alternative means of interacting with the health services and different treatment methods.9 Awareness of the mental health issues of these young people should become a standard part of training for professionals working in these areas.

Correspondence: H Keeley

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, HSE South, 31/32 Fair St, Mallow, Co Cork

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

The SEYLE project is supported through Coordination Theme 1 (Health) of the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7), Grant agreement number HEALTH-F2-2009-223091. The authors were independent of the funders in all aspects of study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

References

1. Sandfort TG, de Graff R, Bijl RV, Schnabel P. Same-sex sexual behaviour and psychiatric disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001; 44: 85-91.

2. Erikson Erik H Identity. Youth and Crisis New York, Norton 1968.

3. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999; 56: 876-80.

4. D’Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clin Child Psychol and Psych. 2002; 7: 433-56.

5. DuRant RH, Krowchuk DP, Sinal SH. Victimization, use of violence, and drug use at school among male adolescents who engage in same-sex behaviour. J Pediatr. 1998; 132: 113-8.

6. Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: Implications for substance use and abuse. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 198-202.

7. Duncan DF. Prevalence of sexual assault victimization among heterosexual and gay/lesbian university students. Psychol Rep. 1990; 66: 65-6.

8. Wichstrom L, Hegna K. Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: A longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003; 112: 144-51.

9. Silenzio VMB, Pena JB, Duberstein PR, Cerel J, Know KL. Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97: 2017-9.

10. King M, McKeown E, Warner J, Ramsay A, Johnson K, Cort C Wright L, Blizard R, Davidson O. Mental health and quality of life of gay men and lesbians in England and Wales: Controlled, cross-sectional study. BJ Psych. 2003; 183: 552-8.

11. Mayock P, Bryan A, Carr N, Kitching K. Supporting LGBTT Lives: A study of the mental health and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual and Transgender people. Glen and BeLonG To Youth Service; Dublin. 2009

12. Wasserman D, Carli V, Wasserman C, Apter A, Balazs J, Bobes J, Brunner R, Corcoran P, Cosman D, Guillemin F, Haring C, Kaess M, Kahn JP, Keeley HS, Keresztény A, Iosue M, Mars U, Musa G, Nemes B, Postuvan V, Reiter-Theil S, Saiz P, Varnik P, Varnik A, Hoven CW.Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE): A randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10: 1-14.

13. Saewyc, EM, Bearinger LH, Heinz PA, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Gender differences in health and risk behaviors among bisexual and homosexual adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998; 23: 181-8.

14. Ryan P. Coming out, fitting in: The personal narratives of some Irish Gay Men. Irish Journal of Sociology. 2003; 12: 68-85.

15. Martin A, Hetrick E. The stigmatization of the gay and lesbian. J Homosex. 1988; 15: 163-83.

16. Igartua KJ, Gill K, Montoro R. Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2003; 22: 15-30.

17. Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel A, Palfrey J, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Peadiatrics. 1998; 101: 895-902.

18. Saewyc EM, Singh N, Reis E, Flynn T. The intersection of racial, gender and orientation harassment in school and health-risk behaviors among adolescents (abstract). J Adolesc Health. 2000; 26: 148.

19. Helsen M, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2000; 29: 319-35.

20. Wills TA, Resko JA, Ainette MG, Mendoza D. Role of parental support and peer support in adolescent substance abuse: A test of mediated effects. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004; 18: 122-34.

21. Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity tracjectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Arch Sex Behav. 2000; 29: 607-27.

22. Bagley C, Tremblay P. Elevated rates of suicidal behaviour in gay, lesbian and bisexual youth. Crisis. 2000; 21: 111-7.

23. Russell ST. Sexual minority youth and suicide risk. Am Behav Sci. 2003; 4: 1241-57.

24. Savin-Williams RC. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority youths: Population and measurement issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001; 69: 983-991.

25. Reach Out: Irish National Strategy for Action on Suicide Prevention 2005-2014. Dublin: Health Service Executive; 2005. 83

an>

an>