Abstract

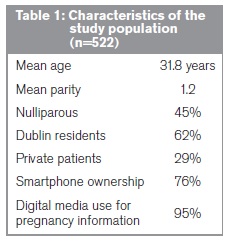

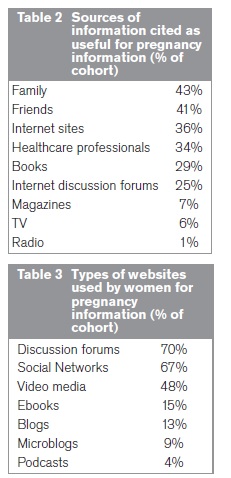

The provision of high quality healthcare information about pregnancy is important to women and to healthcare professionals and it is driven, in part, by a desire to improve clinical outcomes. The objective of this study was to examine the use of digital media by women to access pregnancy information. A questionnaire was distributed to women attending a large maternity hospital. Of the 522 respondents, the mean age was 31.8 years, 45% (235/522) were nulliparous, 62% (324/522) lived in the capital city and 29% (150/522) attended the hospital as private patients. Overall 95% (498/522) used the internet for pregnancy information, 76% (399/522) had a smartphone and 59% (235/399) of smartphone owners had used a pregnancy smartapp. The nature of internet usage for pregnancy information included discussion forums (70%), social networks (67%), video media (48%), e-books (15%), blogs (13%), microblogs (9%) and podcasts (4%). Even women who were socially disadvantaged reported high levels of digital media usage. In contemporary maternity care women use digital media extensively for pregnancy information. All maternity services should have a digital media strategy.

Introduction

Effective communication is a key element of high quality maternity care. In addressing clinical issues this usually occurs in a one-to-one consultation between the woman and her healthcare professional. However, such consultations are limited by time particularly in a busy clinical setting, they usually focus on immediate concerns and they are dependent on the communication abilities of both parties. Before, during and after pregnancy, women are keen to receive information that will promote not only their own well-being but also that of their baby1. Healthcare professionals in turn recognise the importance of providing such information, particularly lifestyle advice and information about the maternity services. Women attending for antenatal care are often given large amounts of written advice at their first hospital visit. Much healthcare information continues to be provided at an individual or population level using traditional communication channels such as leaflets, magazines, television and radio.

Traditional communication channels, however, are limited. They are expensive to develop and disseminate. Written information requires the woman be able to read and to have adequate health literacy to interpret the information meaningfully. Poor health literacy is closely linked to socioeconomic disadvantage and socially disadvantaged women are at increased risk of an adverse clinical outcome2. Therefore, it is often the women who are most in need of information who are least able to access or interpret it. It is challenging to measure by whom traditional communications messages are accessed and what their impact is on health outcomes. Finally, traditional communications are not designed to facilitate ongoing interactions between the woman and her healthcare providers or other women in the community. Communications in the modern world have been revolutionised by the invention of digital media. The development of social network platforms such as Facebook and Twitter has driven interactive, participative and expansive digitally-facilitated communications. By 2011, an estimated 136 million websites were disseminating pregnancy information3. The objective of this prospective study was to examine the use of digital media by women in Ireland in 2012-2013 to access pregnancy information.

Methods

A paper-based anonymous survey was distributed to patients attending a large Dublin maternity hospital from November 2012 to January 2013. The Hospital is a tertiary university maternity hospital delivering over 8,500 babies per annum. It accepts women from all socioeconomic groups across the urban-rural divide and about one in eight of the country’s deliveries occur in the Hospital. Antenatal patients were surveyed while attending the ultrasound department and postnatal patients were surveyed on the postnatal ward. The survey was explained by the researcher and verbal consent for participation was obtained prior to the survey being given out. The survey was then collected in person by the same researcher. Women were asked dichotomous questions about use of a state medical card, smartphone ownership, use of pregnancy Apps, internet use for pregnancy information and the regular purchase of newspapers. Ordinal questions were asked regarding parity, age, age at completion of full-time education, frequency of internet use at home and at work, preferred sources for current affairs information and sources of support and of advice following delivery. Nominal questions were asked about residence, occupation, partner’s occupation, website use in general, the sources used for pregnancy information, both digital and non-digital, the types of digital media that would be useful, for both pregnancy information and for post-natal support. Unstructured questions were asked exploring the nature of pregnancy Apps and pregnancy websites used and of the perceived difficulties accessing pregnancy information. The results were analysed using Microsoft Excel (Version 14.0, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington. 2010).

Women were considered socially disadvantaged is both they and their partner were unemployed, if they had left full-time education before 16 years of age or if they used a state medical card. Population characteristics for the general hospital population were obtained from the Hospital’s Annual Clinical Report4. Differences between groups were tested using X2 analysis and a p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

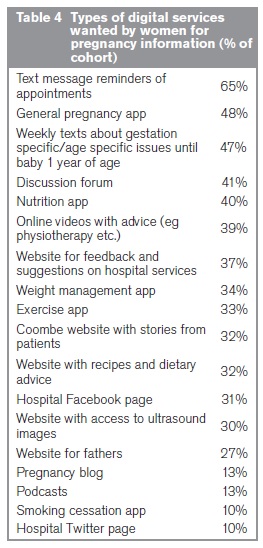

Of the 550 surveys distributed, 542 were collected giving a response rate of 98.5%. A further 20 surveys were excluded from the final analysis as they were incomplete, leaving 522 (94.9%) for the final analysis. Of the 522 respondents, 42% (218/522) completed the survey antenatally and 58% (304/522) postnatally. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences for age, parity or Dublin residency between our cohort and the general hospital population. Overall regular internet use occurred more frequently at home than at work. Of the cohort, 69% (360/522) accessed the internet daily at home compared to 44% (229/522) at work (p<0.01). Only 7% (39/552) used the internet less than once a week at home compared to 49% (256/522) at work (p<0.01). Overall, 95% (498/522) reported that they had used the internet to get information related to their pregnancy or the care of their baby, 76% (399/522) had a smartphone and 59% (235/399) of smartphones owner had used a pregnancy App. Table 2 shows the sources of information women find useful for pregnancy information. Table 3 shows the type of websites women currently use for pregnancy information. Table 4 shows that the type of digital media services women want for pregnancy itself and in caring for their baby.

We found that neither maternal age nor parity influenced the use of digital media for pregnancy information. Of the cohort, 93% (76/82) of women aged less than 30 years and 95% (99/104) of women aged 35 years or more used the internet for pregnancy information (p=0.47). Of the nulliparous women 97% (229/235) used the internet for pregnancy information compared to 94% (270/287) of multiparous women (p=0.06). Even amongst women who were socially disadvantaged, we found high general internet usage (97%, 101/104), high smartphone ownership (61%, 63/104) and widespread usage of pregnancy smartapps among smartphone owners (48%, 30/63).

Discussion

Our study found that women using the maternity services in Ireland in 2012-2013 reported high usage of digital media to obtain pregnancy information, with 95% using the internet to get information about their pregnancy. Almost three quarters of women owned a smartphone and we found high usage of smartapps and social media platforms. Of particular importance, we found that women used digital media more than traditional media sources and that the use of digital media was also widespread amongst socially disadvantaged women. A strength of our study is that it is a large representative sample of the communications behaviour in contemporary maternity services in a developed country. A potential weakness of the study is that it was limited to women with adequate literacy skills to complete a paper-based questionnaire and by the time it is published in the print media the findings may be out of date. The provision of any health information using traditional communication channels can be expensive to produce and to disseminate. There may be time lags between emerging best practice information and dissemination as well as geographical and language limitations5. In contrast, digital media can be developed at a lower cost often leveraging on high quality existing content that has already been developed, for example, for the print media. Content for digital communications can be made available over a long time, globally as well as locally, and in different languages.

It is long established that adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes are increased in women who are socially disadvantaged6,7. However, the most vulnerable women in our society have least access to or the lowest usage of traditional public health information. Our findings that digital media are extensively used by women who are disadvantaged are encouraging. They mean that digital media have the potential to be harnessed beneficially as part of a high quality maternity service and may also have a role in research intervention studies8,9. The use of short message service (SMS) by mobile phone is currently being used successfully in the provision of antenatal care and postnatal care for both mothers and their babies in underdeveloped countries10. One of the problems with traditional public health communications is that we often do not know who receives the information and whether they respond positively or not. The use of digital media, however, can be easily measured with standard software both in terms of what content is accessed and for how long11. It is also possible to study how individuals navigate around a particular website. Thus, we can assess if modifying the communication tool can improve usage. We can also collect information on what socioeconomic or demographic groups use digital platforms, and customise the information for different women.

One of the major social changes in high resource countries with increasing mobilisation of people is the loss of proximity to the extended family. This can leave women feeling isolated during and after childbirth because they may not have strong family support nearby. We found that the most frequently cited websites used by women for pregnancy information were discussion forums and social media platforms. These sites appear to be a useful source of support and give women the opportunity to create a sense of community with other women with similar life experiences. Market research has shown that women turn to digital sources for information and support during pregnancy more than at any other time. A survey asking women which life events prompted them to seek out information from or share opinions with others online found that pregnancy initiated online interaction in 94% of 664 respondents, compared to online interaction in 21% when looking for employment and in 37% when moving home12. This readiness for online engagement in pregnancy means that digital delivery of health promoting information has the potential to be effective. Moderation of such platforms by a healthcare professional also opens up new opportunities for cost effective interventions, for example, lactation counsellors supporting breastfeeding mothers. Conversely, failure of healthcare professionals to provide digital access to high quality information leaves women vulnerable to receiving erroneous or misleading information through unregulated websites and commercial pregnancy Apps.

Our findings are consistent with previous reports8. The gap across social gradients in mobile phone ownership is negligible, as is the use of social networking sites. The expansion of wireless internet and the development of handheld computers such as smartphones and tablets now means that accessing digital media is feasible even while breastfeeding. Based, on our study, we recommend that all maternity services should develop a digital media strategy. Given the pace of change, any strategy will have to be a rolling one capable of embracing innovation quickly. We also recommend that all healthcare professionals in maternity services modernise their communications capabilities on an ongoing basis so that the decisions they and their patients make are well informed3. Finally, we recommend that the effectiveness of all digital communications be measured at regular intervals. Pregnancy is a time in a woman’s life when her health and the health of her family are prioritised1. Digital media communications in pregnancy provide a unique opportunity for healthcare professionals to enhance life-long health and well-being.

Correspondence: A O'Higgins

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital, Cork St, Dublin 8

References

1. Phelan S. (2010). Pregnancy: a "teachable moment" for weight control and obesity prevention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202, 135.e1-8.

2. Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. (2010). "Can this patient read and understand written health information?". JAMA, 304, 76-84.

3. Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. (2011). What is the impact of the internet on decision making in pregnancy? A global study. Birth, 38, 336-45.

4. Annual Clinical Report 2012. Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital. Dublin. 2013

5. Bernhardt JM, Mays D, Kreuter MW. (2011). Dissemination 2.0: closing the gap between knowledge with new media and marketing. Journal of Health Communication, 16, 32-44.

6. Kramer MS, Seguin L, Lydon J, Goulet L. (2000). Socio-economic disparities in pregnancy outcome: why do the poor fare so poorly? Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology, 14, 194-210.

7. Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 39, 263-72.

8. Brendryen H, Kraft P. (2003). Happy Ending: a randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention. Addicition, 103, 487-84.

9. Gibbons C, Fleisher L, Slamon RE, Bass S, Kandadai V, Beck R. (2011). Exploring the potential of web 2.0 to address health disparities. Journal of Health Communication International Perspectives, 16 Suppl 1, 77-89.

10. Pakenham-Walsh N. (2012). Towards a collective understanding of the information of health care providers in low-income countries, and how to meet them. Journal of Health Communication, 17, 9-17.

11. ByteMobile. (2013). Mobile Analytics Report, Santa Clara, USA. Bytemobile.

12. UK Media mum. (2012). Babycentre. London, MediaMum.