V O’Dwyer, S Bonham, A Mulligan, C O'Connor, N Farah, MM Kennelly, MJ Turner

UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital, Cork St, Dublin 8

Abstract

The objective of the study was to identify those women attending for antenatal care who would have benefited from prepregnancy rubella vaccination. It was a population-based observational study of women who delivered a baby weighing ≥500 g in 2009 in the Republic of Ireland. The woman’s age, parity, nationality and rubella immunity status were analysed using data collected by the National Perinatal Reporting System. Of the 74,810 women delivered, the rubella status was known in 96.7% (n=72,333). Of these, 6.4%(n=4,665) women were not immune. Rubella seronegativity was 8.0%(n=2425) in primiparous women compared with 5.2%(n=2239) in multiparous women (p<0.001), 14.7%(n=10653) in women <25 years old compared with 5.0%(n=3083) in women ≥25 years old (p<0.001), and 11.4%(n=780) in women born outside the 27 European Union (EU27) countries compared with 5.9%(n=3886) in women born inside the EU27 countries (p<0.001). Based on our findings we recommend that to prevent Congenital Rubella Syndrome, the health services in Ireland should focus on women who are young, nulliparous and born outside the EU.

Introduction

Rubella is usually a mild febrile illness of little significance in children and adult males.1 About half the infections are subclinical and complications such as encephalitis and haemorrhagic manifestations are rare. Rubella infection in pregnancy, however, is of major public health importance because it is teratogenic in the non-immune woman.1-4 The infection may result in miscarriage, fetal death or birth of an infant with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). The spectrum of CRS depends on the gestational age at the time of infection. During the first trimester up to 85% of infants infected will develop CRS which may result in deafness, cataracts, heart defects, microcephaly, developmental delay, bone changes and hepatosplenic damage. CRS is rare when infection occurs after 20 weeks gestation. CRS is also important because it is preventable by vaccination.3 In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Committee for Europe endorsed combined measles and rubella vaccine programmes which aimed to prevent CRS (<1 case per 100,000 live births) by 2010. The evidence, however, is that this goal was not met.4,5

Rubella has been a notifiable disease in Ireland since 1948.6 A rubella vaccination programme for girls between their 12th-14th birthdays was introduced in 1971.The Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) vaccine was introduced in 1988 for all children at the age of 15 months to two years and for females aged 10-14 years. A second dose of MMR was introduced for all children in 1992. In 1999 the age for the second dose of MMR was dropped from 10-14 years to 4-5 years of age. CRS as a distinct entity only became notifiable in 2004. By 2005, the incidence of rubella was 0.4/100,000 (17 cases) and there were no cases of CRS. The last case was reported in 2004, in contrast to 106 cases of CRS reported between 1975-90.7

In Ireland, women are routinely screened for rubella immunity at their first antenatal visit. The proportion of pregnant women tested by the National Virus Reference Laboratory who were rubella non-immune had fallen to 3.5% by 2004.1 However, recent rubella immunity in Ireland has been sub-optimal, well below the 95% level required to ensure herd immunity to rubella transmission.2,6 This may have been related to parental concerns about the risks of vaccination in young children.8,9 In a recent comparison of rubella seroepidemiology in Australia and 16 European countries, only 5 countries had achieved a protective immunity of >95% among women of childbearing age.2 It was concluded that Belgium, Bulgaria, England/Wales and Ireland were most likely to experience small epidemics. The purpose of this study was to analyse the demography of women booking for antenatal care in Ireland who were rubella seronegative, and to identify those women who may have benefited from prepregnancy vaccination.

Methods

The National Perinatal Reporting System (NPRS) is within the Health Research and Information Division of Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI). It is the only complete national reporting system on births and is responsible for the collection, processing, management and reporting on data of all live births and stillbirths nationally. Since 1999, the ESRI has managed the NPRS on behalf of the Department of Health and the Health Service Executive. For the data the NPRS has developed a custom designed data entry and validation software system and the details of the methodology are published in the Annual Report. In this study a p value of > 0.05 was considered significant.

Demographic details on all women who delivered a baby weighing 500g or more was collected using the Birth Notification Form from all 20 maternity hospitals in 2009. The standard practice is to test the woman’s immunity to rubella at the first antenatal visit and protective immunity is defined as ≥ 10 IU/ml. After delivery rubella immunity is coded as immune, not immune or unknown/not stated. Women who are not immune are offered rubella vaccination post-partum. Nationality was defined as the woman’s place of birth. Nationalities were coded and classified into a set of groups devised by the Central Statistics Office (CSO). Information on a woman’s nationality was reported for the first time in 2004. Information on when the woman took up residence in Ireland is not recorded. For economic reasons, Ireland was one of only three of the 15 European Union (EU) countries who opened up its labour market in 2004 and thus, a country which historically had high rates of emigration then experienced one of the highest rates of immigration in the EU.10

Results

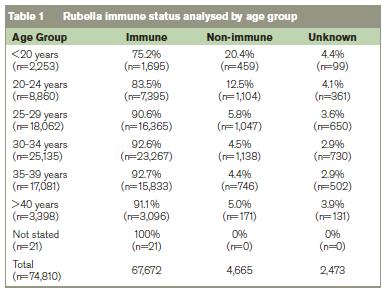

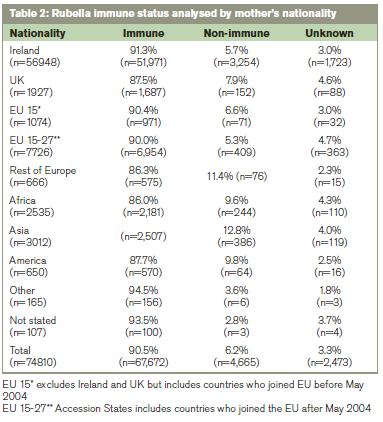

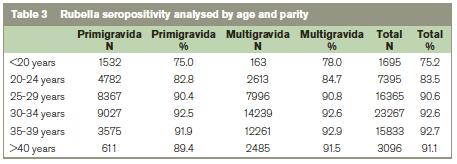

Of the 74,810 women delivered, the rubella status was known in 96.7%. Of the 72,337 women where the rubella status was known, 6.4% (n=4,665) were non-immune. In women where the rubella immune status was known, 8.0% (n=2425) of 30,331 primiparous women were seronegative compared with 5.3% (n=2239) of 42,002 multiparous women (p<0.001). The rubella immune status is shown analysed by age group in Table 1, and by mother’s nationality in Table 2. In 10,653 women <25 years, 14.7% (n=1563) were seronegative compared with 5.0% of the 61,663 women ≥25 years (n=3,102) (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Where the rubella immune status was known, in 6765 women born outside the EU 27 countries 11.5%(n=776) were seronegative compared with 5.9%(n=3,886) in 65,469 women born in the EU 27 countries (p<0.0001). Where the rubella immune status was known in primiparous women from the EU 27 countries (n=27,667), the rubella seronegativity rate was 7.5% (n=2070) compared with 13.4%(n=352) in the 2,620 primiparous women born outside the EU 27 countries (p<0.0001). Where the rubella immune status was known in multiparous women from the EU 27 countries (n=37,799), the rubella seronegativity rate was 4.8%(n=1815) compared with 10.2%(n=424) in the 4,145 women from outside the EU 27 (p<0.001).

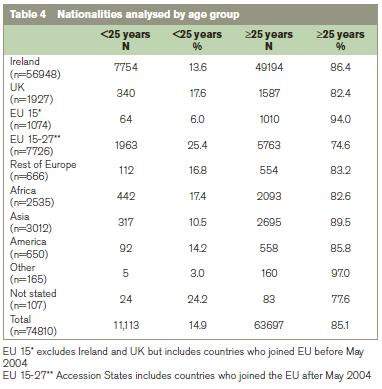

Table 3 shows that age is more influential than parity on the rate of rubella seropositivity. The higher rate of seropositivity in multiparous women is probably due to the policy of offering postpartum vaccination to women identified antenatally as rubella seronegative.6 In view of the findings from the analysis by age and parity, in Table 4 we analysed the nationality groups according to whether they were <25 years of age or ≥25 years ago. This shows that few women born in Africa or Asia were <25 years when they booked for antenatal care, yet their rubella seronegativity rate was high at 9.6% and 12.8% respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

This comprehensive national study shows that the percentage of pregnant women in Ireland with immunity to rubella in 2009 was less than the WHO target of 95%.11 Demographic analysis showed that the women who were most at risk of rubella infection were younger women, first-time mothers and women with a nationality from outside the 27 EU countries. The number of women recorded as rubella non-immune has increased from 3.5% in 2004 to 6.2% in 2009.1 The high rate of rubella seronegativity in women <25 years of age is of concern. This may be related to the low percentage uptake of Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) a decade ago in response to misguided parental concerns about the risks of vaccination.8,9 More recently, immunisation coverage has improved but the 2007 National Report on preventing CRS recommended that routine immunisation activities need to be strengthened to ensure that at least 95% of children receive two doses of MMR.6

In Ireland the increase in rubella seropositivity in older women and in multiparous women is probably due, in part, to antenatal screening for rubella susceptibility and postnatal vaccination (Table 3).6 It may also be due, in part, to the widespread practice of screening for rubella susceptibility in women presenting with a history of primary or secondary infertility, and offering vaccination to women who are seronegative. The increased rate of rubella seronegativity in the general population in 2009 is associated with an increase in immigrants.10 Women coming from non-EU countries, where rubella vaccination was not standard, were more likely to be non-immune to rubella. In the 2007 measles and rubella elimination national strategy document it is recommended that rubella seronegative women should be identified and offered the MMR vaccine.5 This non-EU group of immigrants is a relatively small cohort of women. Focusing on this easily identifiable group for screening and vaccination prepregnancy would be cost-effective. It may also be more cost efficient to vaccinate without serological testing women from countries without rubella programmes.6 Two of the last four confirmed cases of CRS in Ireland were born to women who were non-nationals and the nationality of the other two was unknown.6

In the United Kingdom (UK), there were 13 cases of rubella infection in pregnancy reported between 2005 and 2009. Eight of the 13 were known to have occurred in women born outside the UK.12 Five of the six cases of CRS in the same period occurred in women who were born outside the UK.12 In a Catalonian study of 1538 women, rubella seropositivity was higher in indigenous women (94.9%) compared with immigrant women (89.0%).13 Immigration into Spain increased from 600,000 in 1996 to over 4 million in 2006, mostly from Latin America (36%), Western Europe (21%), Eastern Europe (18%) and Morocco (14%) which led to an increase in susceptibility to rubella infection nationally.14 This increase was associated with a rubella outbreak in babies born to immigrant women.

The high rates of seronegativity in African and Asian women (Table 4) cannot be explained by their young age and are more likely to be explained by vaccination policies where they lived before arriving in Ireland. The two WHO regions that have not set specific goals for controlling rubella by 2009 were Africa and South-East Asia. Both regions have reported an increase in the number of cases of rubella infection in 2000-9, partly due to improved reporting. A decreased rate of rubella immunity amongst African and South-East Asian immigrants has also been reported among women who gave birth at an inner city Canadian hospital between 2002-7.14 We are not in a position to explain the high rate of non-immune in women from the Americas but studies from Spain have reported cases of congenital rubella in women born in Latin America.15 There is evidence that rubella viruses circulating in the Region of Americas may be different phylogenetically.16-18 There are two virus clades (formally called genotypes), which differ in their nucleotide sequences by 8-10%. Some rubella virus genotypes are geographically restricted and Clade 2 viruses have not been found in the Region of the Americas.18

Efforts to harmonise public policies and healthcare practices within the EU include vaccination and surveillance of infectious diseases.11,19 Childhood immunisation programmes are now established in all European countries. Rubella vaccination is part of the universal immunisation programme in all countries in Europe and the Americas. Since 1996, there has been a gradual increase of countries in Eastern Mediterranean region and Western Pacific Region that have introduced rubella-containing vaccines. However, only two of 46 member countries in the African region and four of 11 member countries in the South East Asian region use rubella-containing vaccine. Economic migration into and within the EU is desirable for many reasons. However, immigrants into Ireland after 4-5 years of age may be missed by current vaccination programme. This vulnerable group should ideally be screened before or shortly after arrival in all EU countries.14,19 Particular attention needs to be given to all immigrants from Africa, South-East Asia and the Americas. Such a policy should also improve rubella herd immunity and help meet the renewed WHO European regional goal.20

Correspondence: MJ Turner

UCD Centre for Human Reproduction, Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital, Cork S, Dublin 8

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Cotter S, Gee S, Connell J. Rubella and congenital rubella infection in Ireland. EPI Insight 2005; May pp 2-3.

2. Nardone A, Tischer A, Andrews N, Backhouse J, Theeten H, Gatcheva N, Zarvou M, Kriz B, Pebody RG, Bartha K, O’Flanagan D, Cohen D, Duks A, Griskevicius A, Mossong J, Barbara C, Pistol A, Slac? iková M, Prosenc K, Johansenr K, Millera E. Comparison of rubella seroepidemiology in 17 countries: progress towards international disease control targets. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008; 86:118-125.

3. Lee JY, Bowden S. Rubella virus replication and links to teratogenicity. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13:571-87.

4. Forsgren M. Prevention of congenital and perinatal infections. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:2-4.

5. WHO Regional Committee for Europe. Renewed commitment to measles and rubella elimination and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome in the WHO European region by 2015. Moscow. September 2010.

6. Eliminating measles and rubella and preventing congenital rubella infection: a situation analysis and recommendations. Committee of the Department of Health and Children 2007.

7. Jennings S, Thornton L. The epidemiology of rubella in the Republic of Ireland. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev 1993; 16:115-17.

8. Ramsey ME, Yarwood J, Lewis D, Campbell H, White JM. Parental confidence in measles, mumps and rubella vaccine: evidence from vaccine coverage and attitudinal surveys. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52:912-16.

9. Murphy JF. Fallout of the enterocolitis, autism, MMR vaccine paper. Ir Med J 2011; 104:36.

10. Quinn E. Policy analysis report on asylum and migration: Ireland mid-2004 to 2005. European Migration Network, 2006.

11. World Health Organization (WHO). Eliminating measles and rubella and preventing congenital rubella infection: WHO European Region strategic plan 2005-2010.

12. Guidance on viral risk in pregnancy. Health Protection Agency, January 2011.

13. Dominguez A, Plans P, Espunes J, Costa J, Torner N, Cardenosa N, Plasencia A, Salleras L. Rubella immune status of indigenous and immigrant pregnant women in Catalonia, Spain. Eur J Public Health 2007; 17:560-64.

14. McElroy R, Laskin M, Jiang D, Shah R, Ray JG. Rates of rubella immunity among immigrant and non-immigrant pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009; 31:409-13.

15. Carnicer-Pont D, Pena-Ray I, de Aragon M, de Ory F, Dominguez A, Torner N, Caylà JA,Find all citations by this author (default). Regional Surveillance Network. The Regional Surveillance Network. Eliminating congenital rubella syndrome in Spain: does massive immigration have any influence? Eur J Public Health 2008; 18:688-690.

16. Frey TK, Abernathy ES, Bosma TJ, Starkey WG, Corbett KM, Best JM Katow S, Weaver SC . Molecular analysis of rubella virus epidemiology across 3 continents, North America, Europe, Asia, 1961-1997. J Infect Dis 1998; 178:642-50.

17. Zheng DP, Frey TK, Icenogle J, Katow S, Abernathy ES, Song KJ, XU WB, Yarulin V, DestjatskovaRG, Aboudy Y, Enders G, Croxson M. Global distribution of rubella virus genotypes. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:1523-30.

18. Best JM, Castillo-Solorzano C, Spika JS, Icenogle J, Glasser JW, Gay NJ, Andrus J, Arvin AM. Reducing the global burden of congenital rubella syndrome: Report of the World Health Orgainsation Steering Committee on research related to measles and rubella vaccines and vaccination, June 2004. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:1890-7.

19. Pandolfi E, Chiaradia G, Moncada M, Rava L, Tozzi AE. Prevention of congenital rubella and congenital varicella in Europe. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:16-20.

20. Muscat M, Zimmerman L, Bacci S, Bang H, Glismann S, Molbak K, Reef S, EUVAC.NET group. Toward rubella elimination in Europe: An epidemiological assessment. Vaccine 2012; 30:1999