Abstract

Alcohol consumption is causally related to cancer of the upper aero-digestive tract, liver, colon, rectum, female breast and pancreas. The dose response relationship varies for each site. We calculated Ireland’s cancer incidence and mortality attributable to alcohol over a 10-year period. Between 2001 and 2010, 4,585(4.7%) male and 4,593(4.2%) female invasive cancer diagnoses were attributable to alcohol. The greatest risk was for the upper aero-digestive tract where 2,961(52.9%) of these cancers in males and 866(35.2%) in females were attributable to alcohol. Between 2001 and 2010, 2,823(6.7%) of male cancer deaths and 1,700(4.6%) of female cancer deaths were attributable to alcohol. Every year approximately 900 new cancers and 500 cancer deaths are attributable to alcohol. Alcohol is a major cause of cancer after smoking, obesity and physical inactivity. Public awareness of risk must improve. Over half of alcohol related cancers are preventable by adhering to Department of Health alcohol consumption guidelines.

Introduction

Alcohol consumption causes 3.8% of global mortality. Europe and America have the highest death rates, 6.5% and 5.6% respectively1. The main causes of alcohol related death in European men are cirrhosis (26%), unintentional injury (23%) and cancer (17%). In European women, the main causes of alcohol related death are cirrhosis (37%) and cancer (31%)2. In Ireland the proportion of alcohol related deaths from cancer is higher than the European average, 20.7% for men and 38.8% for women3. Cancer incidence due to alcohol was quantified for eight European counties (but not Ireland) as part of the EPIC study4. This found 10% of male and 3% of female cancer incidence is attributable to current or former alcohol consumption.

There is a proven link between alcohol consumption and cancer of the upper aero-digestive tract (lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus), liver, colon, rectum and female breast, with a small statistically significant increased risk for pancreatic cancer with high intake5,6. There is no threshold below which there is no increased cancer risk. The strength of the relationship varies for different sites. The relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer of the upper aero-digestive tract is greatest, with more than a doubling in risk from an average consumption of 50g of pure alcohol per day2. For female breast cancer each additional 10g of pure alcohol per day is associated with a 7% increase in relative risk7. For colorectal cancer, consumption of 50g per day increases the risk by 10-20%2. The molecular mechanisms for alcohol-associated carcinogenesis focus on acetaldehyde, the first and most toxic ethanol metabolite, as a cancer-causing agent. Ethanol may also stimulate carcinogenesis by inhibiting DNA methylation and by interacting with retinoid metabolism. Alcohol-related carcinogenesis may interact with other factors such as smoking, diet and co-morbidities, and depends on genetic susceptibility8,9.

The volume of alcohol consumed in Ireland increased dramatically over the past 50 years. In 1963 average consumption of pure alcohol was 6.2 litres per adult per year. In 2002 consumption reached a peak at 14.2 litres (compared with a European average of 9.1 litres and a global average of 6.1 litres at that time). In 2010 Ireland’s consumption reduced to 11.9 litres10. While this is now more in line with the European average, it remains a concern especially as one in five in Ireland is an abstainer11. The objective of this study is to calculate the proportion of cancer incidence and cancer mortality in Ireland that was due to alcohol consumption over the ten year period, 2001 to 2010.

Methods

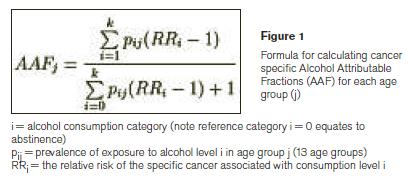

The alcohol attributable fraction (AAF) is used to estimate the proportion of a condition that is causally related to alcohol. The cancer AAF is a function of population age-specific prevalence (P) of alcohol consumption and relative risk (RR) estimates of acquiring a specific alcohol-related cancer, using the formula in Figure 1. AAFs can be applied to national population data on incidence and mortality to determine the number of new cancers and cancer deaths, for a defined time-period, that are causally related to alcohol consumption. Previous research calculated AAFs for all alcohol-related mortality in Ireland3. These researchers used alcohol consumption data from the Survey of Lifestyles, Attitudes and Nutrition (SLAN) in 200712 and adjusted it upwards to account for the underestimation by self-reporting. We used their adjusted prevalence data in this study and their consumption categories i.e. abstainer (the reference category), low risk, risky and high risk. Consumption is recorded in grams per day.

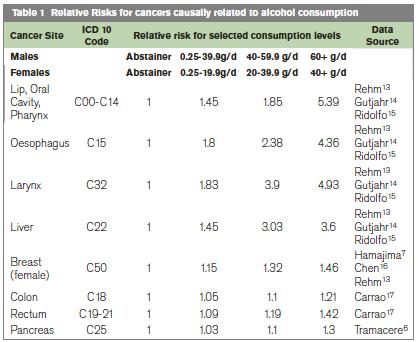

A literature review of meta-analyses/systematic reviews identified RRs of specific cancers that are causally related to alcohol. These RRs were applied to the SLAN categorical variables of alcohol consumption in Ireland, Table 1. We obtained national cancer incidence and mortality data, for cancers known to have a causal relationship with alcohol consumption, for the 10 year period 2001-2010. Cancer incidence data were obtained from the National Cancer Registry of Ireland. Cancer mortality data were obtained from the Central Statistics Office. The derived AAFs for each cancer by 5-year age group, for males and females, were collated with cancer incidence and mortality data to determine the number of alcohol attributable cancers in each age group. The total number of new cancer cases and deaths between 2001 and 2010 attributable to alcohol was then calculated, as were the overall proportions attributable to alcohol.

Results

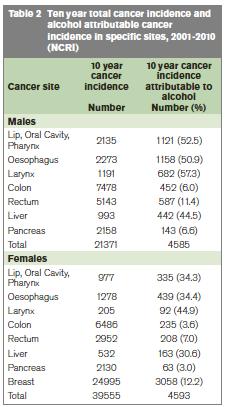

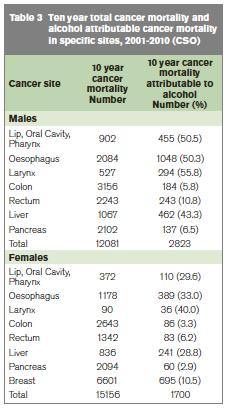

Table 2 shows total 10-year cancer incidence in sites known to be impacted by alcohol and the number (%) calculated as being attributable to alcohol. Table 3 provides the results for cancer mortality attributable to alcohol.

Incidence

Between 2001 and 2010, there were 21,371 invasive cancers diagnosed in men in sites where alcohol is known to play a causative role; 4,585 were attributed to alcohol i.e. 21.5% of all cancers in those sites and 4.7% of all invasive male cancers, Table 2. Of the 4,585 alcohol-attributable cancers diagnosed in men, 64.5% were in the upper aero-digestive tract (lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus). Alcohol was considered responsible for 52.9% of male upper aero-digestive tract cancers, in contrast with 6% of colon cancers, 11.4% of rectal cancers and 7% of pancreatic. Alcohol played a causative role in 44.5% of male liver cancers. Between 2001 and 2010, 39,555 invasive cancers were diagnosed in women in sites where alcohol is known to play a causative role; 4,593 were considered attributable to alcohol i.e. 11.6% of all the cancers in these specific sites and 4.2% of all female invasive cancers, Table 2. Among females, upper aero-digestive tract cancers were also most impacted, with 866 (35.2%) of the 2,460 cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract attributable to alcohol. Only 3.6% of colon, 7% of rectal and 3% of pancreatic cancers were attributed to alcohol. However, 12.2% of breast cancers, 305 cases annually, were attributed to alcohol. This accounted for two-thirds of all cancer diagnoses attributable to alcohol in females.

Mortality

Between 2001 and 2010, 6.7% of all male cancer deaths and 4.6% of all female cancer deaths were attributable to alcohol. There were 12,081 male cancer deaths in sites known to be impacted by alcohol and of these 2,823 (23.4%) were attributed to alcohol. Like cancer incidence, most alcohol-related cancer deaths in men were in the upper aero-digestive tract (63.6%). Among females there were 15,156 cancer deaths in sites known to be impacted by alcohol and 1,700 (11.2%) were attributed to alcohol. Breast cancer deaths contributed to 40.9% of alcohol related cancer deaths.

Discussion

Alcohol is a group 1 carcinogen. It is one of the most important causes of cancer after tobacco smoking, obesity and physical inactivity. Yet, the public is not generally aware of the risk of cancer from alcohol. Though the overall risk of cancer from alcohol is low, this study shows that, every year in Ireland approximately 5% of newly diagnosed cancers and cancer deaths are attributed to alcohol i.e. a yearly average of 917 new cases and 452 deaths between 2001 and 2010. This is similar to international findings, with regional differences reflecting variations in alcohol consumption4,18.

The cancer risk from alcohol varies for different parts of the body. The greatest risk is to the upper aero-digestive tract where it explains over 50% of these cancers in men and over one-third in women in Ireland. The risk of cancer in the upper aero-digestive tract is strongly related to the amount of alcohol consumed19. Furthermore, alcohol consumption together with tobacco smoking can explain 75% of these cancers, as alcohol and tobacco act synergistically. Therefore the majority of cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract could be avoided by not smoking and moderating alcohol use20,21. Just 12.2% of breast cancers were attributable to alcohol but most (67%) of all the female cancers attributable to alcohol were breast cancers. This is simply because breast cancer is a common disease. Other research world-wide concurs that 60% of female cancers attributable to alcohol occur in the breast18.

While the impact on breast cancer is modest in percentage terms, is important at a population level. It is important that women who are at higher risk of breast cancer have information on the additional risk from alcohol. In relation to liver cancer, the EPIC study found that the average proportion of liver cancer incidence due to alcohol, in eight European countries, was 33% for men and 18% for women4. The corresponding figure for Ireland was higher at 44.5% for men and 30.6% for women. It is also notable that between 2001 and 2010 recorded liver cancer mortality was higher than liver cancer incidence and the variation was greater in women. One possible hypothesis is that some deaths from ‘metastatic liver cancer’ may be recorded on death certificates as ‘liver cancer’. This warrants further study.

Department of Health alcohol consumption guidelines are 17 units per week for males and 11 units per week for females. The EPIC study showed that 50% of alcohol-related cancer incidence was due to drinking over recommended limits4. However there is no threshold of consumption below which there is no risk. Even small volumes of alcohol consumption, within the recommended consumption limits, have been shown to contribute to breast cancer13.

There are some limitations in the derivation and application of attributable risk estimates. Firstly, the AAF is dependent on the accuracy of population alcohol consumption data and on the RRs used in the calculations. We used adjusted consumption data to overcome the issue of underestimation by self reporting. Using adjusted data is in itself limiting as it assumes a symmetrical distribution across consumption categories. Relative risk estimates in the epidemiological literature vary between different meta-analyses but are broadly similar. Confidence limits associated with these RRs need to be borne in mind but as with other calculations of AAFs15, we have not developed methodologies to calculate confidence intervals for each AAF. Therefore there is some uncertainty surrounding the estimate presented. Secondly, the interpretation of attributable risk should be approached with caution, particularly in relation to a multifactorial disease such as cancer. Removal of exposure does not reduce risk to zero in the individual or the population, given the existence of other significant risk factors. However, it can be used to estimate the potential reduction in an individual’s risk of a particular cancer, or indeed the burden of disease that could be prevented in the population. Finally there is a long lag-time between consumption of alcohol and eventual onset of or death from cancer. As such, the burden of cancer from 2001-2010 more accurately reflects patterns of alcohol consumption in the 1980s and 1990s.

A public and health professional information campaign is needed to highlight the risk of alcohol on cancer. This should reinforce that drinking within Department of Health guidelines could prevent half of alcohol-related cancers. It should highlight the huge risk of upper aero-digestive cancer from alcohol and the synergistic impact of smoking. Women need to know about the risk of breast cancer from even low levels of consumption so that they can make an informed choice about their alcohol consumption.

Correspondence: M Laffoy

National Cancer Control Programme, 100 Parnell Street, Dublin 1

Acknowledgements

S Deady, National Cancer Registry for providing cancer incidence data and A Cahill and G Cosgrove, Department of Health, for data on cancer mortality. Our thanks to D Carey, HSE for statistical advice.

References

1. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J, Alcohol and Global Health 1; Global Burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009; 373; 2223-2233.

2. Alcohol in the European Union: consumption, harm and policy approaches. WHO; 2012.

3. Martin J, Barry J, Goggin D, Morgan K, Ward M, O’Suilleabhain T. Alcohol attributable mortality in Ireland. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2010; 45:379-386.

4. Schütze M, Boeing H, Pischon T, Rehm J, Kehoe T, Gmel G, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Dahm C, Overvad K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault M, Trichopoulou A, Benetou V, Zylis D, Kaaks R, Rohrmann S, Palli D, Berrino F, Tumino R, Vineis P, Rodríguez L, Agudo A, Sánchez M, Dorronsoro M, Chirlaque M, Barricarte A, Peeters P, van Gils C, Khaw K, Wareham N, Allen N, Key T, Boffetta P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Romaguera D, Wark P, Riboli E, Bergmann M Alcohol attributable burden of incidence of cancer in eight European countries based on results from prospective cohort study. Br Med J 2011; 342: d1584.

5. IARC Monographs. Personal habits and indoor combustions; Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. IARC. WH0, Lyon, France 2012. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100E/100E-06-Table2.13.pdf . Accessed July 2013

http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100E/100E-06-Tables2.14.pdf . Accessed July 2013

http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100E/100E-06-Table 2.25.pdf . Accessed July 2013

6. Tramacere I, Scotti L, Jenab M, Bagnardi V, Bellocco R, Rota M, Corrao G, Bravi F, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C. Alcohol drinking and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis of the dose-risk relation. Int J Cancer 2010; 126: 1474-1486.

7. Hamajima N, et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002; Nov 18; 87: 1234-45.

8. Seitz H, Stickel F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-medicated carcinogenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer 2007; 599-612.

9. Seitz H, Pelucchi C, Bagnardi V, La Vecchia C. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of alcohol and breast cancer: Update 2012. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 2012; 1-9.

10. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. World Health Organisation.

http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A1025?lang=en&showonly=GISAH . Accessed July 2013

11. Steering group report on a National Substance Misuse Strategy.

February 2012. Department of Health. Dublin. www.dohc.ie Accessed July 2013

12. Department of Health and Children; SLAN 2007; Survey of Lifestyle. Attitudes and Nutrition in Ireland; Main Report; 2008. www.dohc.ie Accessed July 2013

13. Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Graham K, Rehn N, Sempos CT, Frick U, Jernigan D: Alcohol use. In Comparative quantification of health risk: Global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Volume 1. Edited by Ezzati MLA, Rodgers A, Morray CJ. Geneva: The WHO; 2004:959-1108. Accessed July 2013

14. Gutjahr E, Gmel G, Rehm J: Relation between average alcohol consumption and disease: an overview. European Addiction Research 2001, 7:117-127.

15. Ridolfo B, Stevenson C: The quantification of drug caused mortality and morbidity in Australia, 1998. Canberra (AS): Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2001.

16. Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willet WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2011 Nov 2;306:1884-90.

17. Carrao G., Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004; 38: 613-9.

18. Boyle P, Levin B. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol frequency and the risk of head and neck cancer. Adapted from Boyle 2008. World Cancer report, 2008. World Health Organisation Lyon 2008.

19. Altieri A Bosetti C. Gallus S . Wine , beer and spirits and the risk of oral and pharyngeal caner: a case control study from Italy and Switzerland. Oral Oncol. 2004; 40;904-9.

20. Doll R. Forman D. La Vecchia C. Woutersen R. Alcoholic beverages and cancers of the digestive tract and larynx. In: Macdonald, I., ed. Health Issues Related to Alcohol Consumption. 2nd ed. Oxford: ILSI Europe-Blackwell Science Ltd, 1999. pp. 351–393.

21. Bofetta P, Hashibe M, LaVechia , Zatonski W, Rehm J. The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking. Int. J. Cancer 2006; 119: 884-887.