Introduction

The debate regarding the “feminisation” of medicine ripples continuously below the surface. Recent revised selection mechanisms to medical schools in Ireland, introduced in 2009 following the Fottrell report, appear to have unintentionally marginally reduced the proportion of female entrants to medical school provoking a media debate.1,2 There was an official response.3 Similar media debates have occurred in the UK. 4 Medicine was once a male-dominated profession reflecting the male preponderance in medical schools. Subsequently an increase in female undergraduate entrants has led to an even gender balance or slight female dominance in medical schools.5 Any ideal admission process should be fair, transparent and without bias. There is no ideal gender composition nor is there an ideal demography in medical schools beyond ensuring that the population studying to become the doctors of tomorrow is broadly representative of society as a whole. Equity of access to medical school is not simply a gender question. There is concern regarding the access of minority groups and perhaps socio-economically disadvantaged candidates to a place in medical school when traditional tests are used.5,6 Elsewhere, innovative approaches to entry and selection have not entirely resolved this issue and data is conflicting.7,8 The UK data suggests that inclusion of an adjunct admission test, the UK Clinical Aptitude Test or UKCAT, may have slightly altered the gender balance in medical schools reducing the previous female dominance.9

Since 2009, entry and selection to medical school in Ireland is determined by scoring performance in six subjects in a single sitting of the state run school exit examination the Leaving Certificate (or equivalent), wherein matriculation requirements have been met and the score achieved in an adjunct admission test the Health Professions Admission Test or HPAT-Ireland. To be eligible to apply to medicine candidates must score above 480 points noting that an A1 grade of greater than 90% represents 100 points, an A2 grade of 85-89% represents 90 points etc. Furthermore, Leaving Certificate scores are moderated above 550 points and the maximum achievable Leaving Certificate score for the cohort evaluated was 560 points (this has changed in 2012 since the introduction of bonus maths points) while the maximum achievable HPAT-Ireland score is 300 points. (Therefore maximal entry scores were 860)10 This latter test consists of a 2 ½ hour multiple choice paper comprising 3 sections; 1) Logical Reasoning and Problem Solving; 2) Interpersonal Understanding; and 3) Non-Verbal Reasoning. As gender neutrality was a consideration in the adjunct admission test procurement process and is a consideration in any fair entry and selection mechanism, it is reasonable to evaluate the gender impact of the revised approach to entry and selection to medical schools in Ireland.

Methods

A National Research Group, Evaluating Revised Entry and Selection Mechanisms to Medicine, has been convened under the auspices of the Council of Deans of Faculties of Medical Schools in Ireland. The Research group comprises representation from academic medical education staff of each medical school, university admission officers, the Central Applications Office (CAO) and external experts. All candidates who sit HPAT-Ireland sign a waiver allowing their results to be analysed for research purposes. Leaving Certificate results and gender profiles were obtained from the CAO. Ethical approval for the research was processed in UCC. The following data was collected and gender profiles collated for the years between 2009 -2011 inclusive; Leaving Certificate scores of all applicants, HPAT-Ireland scores of all applicants (where medicine was the first or lower ranked choice) and gender profile of applicants and entrants in 2008. The analysis excluded candidates who presented A-levels, mature entrants and those admitted under specialised entry schemes for students with a disability or those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Some HPAT-Ireland performance data was obtained directly from the Australian Council for Education Research (ACER) the purveyors of HPAT –Ireland and is reproduced here with their permission. This data has been verified independently by the authors. All data was entered into and analysed using Stata version 12.1.

Results

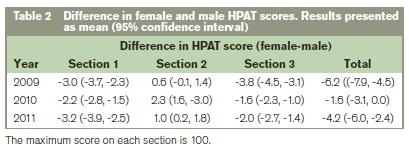

Gender performance in the Leaving Certificate varies from year to year however since 2009 eligible male applicants to medical school have tended to slightly outperform females as is evident in Table 1. The observed differences of HPAT- Ireland total scores and HPAT-Ireland subsection performance of all applicants is outlined in Table 2. There is a slight gender difference in HPAT-Ireland performance favouring males most evident in 2009 but less apparent in 2010 or 2011. There is persistent subtle gender patterns at the level of HPAT-Ireland subsections with males consistently outperforming females in section 1. Logical Reasoning and Problem Solving and section 3 Non-Verbal Reasoning whilst females consistently outperform males in section 2 Interpersonal Understanding.

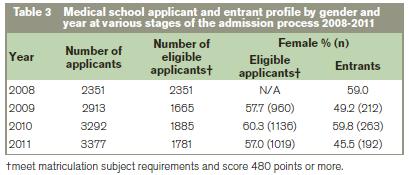

The gender profile at various stages in the process from application to admission is presented in table 3 including data from 2008, the year before revised mechanisms were introduced and for 2009-2011 inclusive i.e. the 3 years following the introduction of the reforms. As is evident, females predominate in the total applicant pool, and in the eligible applicant pool however the gender representation of successful applicants i.e. those who secure a place in medical school has varied annually with near equal gender distribution in 2009, female dominance in 2010 and male dominance in 2011.

Discussion

The strength of this data analysis lies in the fact that it evaluates gender trends across the entire applicant and entrant cohorts for a number of years. The analysis aims to present trends to inform discussion. It should be noted that the gender balance in medical schools was not an issue of concern to the Fottrell Group nor was it a consideration. Rather, the report focussed on aligning entry and selection processes in Ireland with practices elsewhere and removing the perceived negative educational consequences of the “Points race” for all applicants. It is desirable that all high stakes tests are gender neutral. The Leaving Certificate has not been subjected to this scrutiny and indeed may favour females as indeed do other school exit examinations.11,12 Previous evaluations of entry and selection mechanisms have been limited by the very small numbers of students and the fact that only modified versions of the HPAT- Ireland were used.13 The mean scores of eligible male applicants in both tests used to determine admission are higher than female applicants and, although these are not statistically significant, the demand for places leads to clustering of applicant scores at an admission threshold so that such small statistically insignificant differences can affect outcomes.14

In relation to the HPAT-Ireland, there are some subtle gender differences in scores at subsection level and a small gender difference in total HPAT-Ireland score. This was perhaps most evident in 2009 but is overall less evident thereafter. At an applicant cohort level, it is hard to attribute overwhelming significance to these findings. The subtle differences observed in gender performance at the level of HPAT-Ireland subsections would appear to partially compensate for each other. Furthermore recent proposed changes to the scoring of HPAT-Ireland ,which will reduce the weighting applied to section 3 may reduce the gender differential observed in total HPAT-Ireland scores .15 The largest controlled study evaluating the topic of MCQs and gender bias was conducted in the US in 1997 involving millions of students across a range of ages. It noted a slight gender bias favouring males who appeared to perform better in items requiring the interpretation of a figure or graphical information such as may occur in sections 1 and 3 of HPAT-Ireland.16 It is interesting that males may also outperform females in the most commonly used adjunct admission test in the UK where similar factors may be at play.9

Our analysis of medical school applicants in 2009-2011 inclusive suggests that male applicants outperform female applicants in the Leaving Certificate and, although overall the differences are small, as the entry and selection process is still weighted in favour of the Leaving Certificate any gender differences in such test scores theoretically has approximately twice the effect of a similar difference in gender performance in HPAT-Ireland. This finding surprised us as it is known that females generally outperform males in such tests and previous female dominance in medical school was secondary to superior Leaving Certificate performance. 11. We wonder whether external factors such as the prevailing economic climate may have influenced applicant behaviour. It is known that male applications to medicine tend to increase in times of economic uncertainty.17 Perhaps the apparent security offered by a career in medicine has made such an option more attractive to high academic performing males in Ireland. Moderation and subsequent adjustment of the benefit of scoring above 550 points in the Leaving Certificate was introduced to remove the negative educational impact of the “points obsession” for all applicants and our data suggests that in recent years males would be expected to be most affected by such moderation. Medicine is the only course where such a moderation applies. It is perhaps the most contentious aspect of the reforms introduced.

Obviously a range of factors affect academic performance and test performance in general including motivation and commitment quite apart from any gender issue.18 Females had predominated in medical schools in Ireland for some years. This is a trend mirrored internationally and not an Irish phenomenon.5 In 2009, this trend was adjusted transiently but reverted in 2010 with females again predominating and this pattern has appeared to change annually. It is difficult to establish the impact of the stipulation that points must be scored from matriculation subjects in a single sitting as the gender profile of applicants who repeated the Leaving Certificate in the past was not a focus of this work, but it will now be examined. The perception that the inclusion of the HPAT-Ireland test in entry and selection decisions actively disadvantages females is not however borne out in any conclusive fashion by the evidence. The gender difference in mean gender scores in the total HPAT-Ireland and Leaving certificate is small. The entry and selection system is still weighted in favour of leaving certificate scores. In 2010, where least difference was evident in male and female leaving certificate scores and HPAT-Ireland scores, almost 60% of entrants were female.

The historic relative over-representation of females in medical school is a sensitive and emotive issue. All agree that selection to the profession should focus on selecting the best potential doctors but the debate as to the precise mechanism to be employed continues.19 Proxy measures such as knowledge based tests and adjunct admission tests are, and will continue to be, widely used in a merit based system. The demographic of the medical workforce is of interest as this will inevitably influence systems based work practices but perhaps the extent of the gender aspect of this influence is sometimes overstated as flexible work practices in Healthcare are required to retain all graduates and not just females.20,21 The gender debate may have gained attention however policy makers are more concerned about socio-demographic equity. Concerns regarding access to commercial HPAT preparatory courses and repeat effects have already led to recommendations being considered by all medical schools.15

In summary, the data analysis to date does not support any evidence of a definite gender bias associated with the introduction of the adjunct admission test HPAT- Ireland. This will continue to be analysed on an ongoing basis.

Correspondence: S O’Flynn

Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Brookfield Health Sciences Complex, UCC, Cork

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgments

All of the other members of the Research Group - B Powderly UCD representing Council of Deans of Faculties with Medical Schools of Ireland; F Dunne, NUIG; D Mc Grath, UL; M Hennessy, TCD; J Last, UCD; and R Arnett, RCSI. I Gleeson Central Applications Office (CAO) who is a member of the Group and the Admission Officers in each school whose insights continue to influence all aspects of the research.

Funding

Financial support received from the Higher Education Authority.

References

1. Medical education in Ireland: a new direction Department of Health & Children, Dublin, 2006.

2. Houston M. Welcome for more men doing medicine. The Irish times. 25-08-09.

3. (CDFMSI). Letters to the Editor - Gender balance in medicine. Council of Deans of Faculties with Medical Schools of Ireland: Irish Times; 2009.

4. Laurance J. the medical timebomb :too many women doctors. The Independent. 2004.

5. The demography of medical schools : a discussion paper. British Medical Association. London: BMA, 2004.

6. McManus IC, Woolf K, Dacre J. The educational background and qualifications of UK medical students from ethnic minorities. BMC medical education. 2008;8:21. Epub 2008/04/18.

7. Puddey IB, Mercer A, Carr SE, Louden W. Potential influence of selection criteria on the demographic composition of students in an Australian medical school. BMC medical education. 2011;11:97.

8. iffin PA, Dowell JS, McLachlan JC. Widening access to UK medical education for under-represented socioeconomic groups: modelling the impact of the UKCAT in the 2009 cohort. BMJ. 2012;344:e1805.

9. James D, Yates J, Nicholson S. Comparison of A level and UKCAT performance in students applying to UK medical and dental schools in 2006: cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c478.

10. CAO. Summary report; New selection criteria for undergraduate entry to Medicine 2009. .

11. Hyland A. Commission on the Points System Final Report and Recommendations. Department of Education, 1999.

12. McManus IC, Powis DA, Wakeford R, Ferguson E, James D, Richards P. Intellectual aptitude tests and A levels for selecting UK school leaver entrants for medical school. BMJ. 2005;331:555-9.

13. Halpenny D, Cadoo K, Halpenny M, Burke J, Torreggiani WC. The Health Professions Admission Test (HPAT) score and leaving certificate results can independently predict academic performance in medical school: do we need both tests? Ir Med J. 2010;103:300-2.

14. O'Flynn S, Fitzgerald AP, Mills A. Modelling the impact of old and new mechanisms of entry and selection to medical school in Ireland: who gets in? Ir J Med Sci. 2013.

15. O'Flynn S, Mills,A, Fitzgerald,T. National research group evaluating revised entry mechanisms to medicine Interim Report -School Leaver Entrants. 2012.

16. Cole N. The ETS Gender Study: How Females and Males Perform in Educational Settings. Princeton: Educational Testing Service (ETS), 1997.

17. AAMC. The Changing Gender Composition of US Medical School Applicants and Matriculants, Association of American Medical Colleges Report. 2012.

18. Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2002;324:952-7.

19. O'Flynn S. Entry and selection to medical school– Do we know what we should measure and how we should measure it? Medical Education - The state of the Art: Nova Science Publishers; 2010. p. 17-29.

20. Weizblit N, Noble J, Baerlocher MO. The feminisation of Canadian medicine and its impact upon doctor productivity. Medical education. 2009;43:442-8.

21. Meghen K, Sweeney, C, O'Flynn, S, Linehan, C, Boylan, GB. Women in Hospital Medicine: Facts, Figures and Personal Experiences. Ir Med J. 2013; 106: 39-42.