F Tareen1, D Coyle1,2, OM Aworanti2, J Gillick1,2

1Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12

2Children’s University Hospital, Temple St, Dublin 1

Abstract

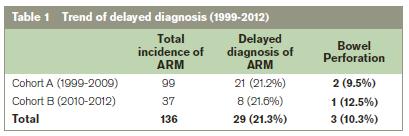

Delayed diagnosis of anorectal malformation (ARM) is an avoidable event associated with significant complications and morbidity. Previous studies have suggested higher than expected rates of delayed diagnosis, especially when a threshold of 24 hours of life is used to define delayed diagnosis. The aim of this study is to highlight the prevalence of delayed diagnosis of ARM in Ireland and to determine if any improvement in rates of delayed diagnosis of ARM has occurred since we previously examined this problem over a 10 year period in 2010. We compared trends in the incidence of delayed diagnosis of ARM between two cohorts, A (1999-2009) and B (2010-2012). Delayed diagnosis was defined as one occurring after 48 hours of life. Delayed diagnosis occurred in 29 cases (21.3%) in total, with no difference in the incidence of delayed diagnosis between cohort A (21 patients [21.2%]) and cohort B (8 patients [21.6%]) being recorded. The rate of bowel perforation in patients with delayed diagnosis was 10.3% (3 cases). Our findings highlight the importance of a careful, comprehensive clinical examination in diagnosing ARM and suggest this is still sub-optimal. We strongly support the use of a nationally devised algorithm to aid diagnosis of ARM in order to avoid life-threatening complications.

Introduction

Anorectal malformation (ARM) is a common paediatric congenital malformation with an incidence of approximately 1:2500 to 1:50001. Its occurrence has a male preponderance and it is associated with several syndromes such as trisomy 21 and Cat Eye syndrome. Early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention is the key to successful outcome. It is expected that most cases should be diagnosed within the first 24 hours of life on routine inspection of the perineum, although some are only diagnosed following the development of features such as abdominal distension or bilious vomiting. The importance of perineal examination was seen as early as the second century BC, when Sonarus recommended anal examination for all neonates2. While routine neonatal examination has been strongly advocated in the literature, and practiced widely, the delayed diagnosis of ARM continues to be a common problem3,4. Female neonates with ARM frequently exhibit anatomical anomalies more facilitative to the passage of meconium than in males and thus delayed diagnosis appears to be more common in this population.

The delay in diagnosis is associated with early life-threatening complications such as sepsis, bowel perforation and death. Late complications include constipation and mega-rectum. These complications not only alter the surgical management but cause significant social and psychological morbidity5-7. We have previously carried out a 3 year review demonstrating an unacceptably high rate of delayed diagnosis of ARM with a median time to diagnosis of day 4 of life8. The aim of this study is to highlight the current prevalence of delayed diagnosis of ARM in Ireland and to determine if any improvement in rates of delayed diagnosis of ARM has occurred since our previously published study in 2010.

Methods

The records of all patients diagnosed with ARM presenting to Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin and Children’s University Hospital Temple Street between 1999 and 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. These 2 centres are the regional referral units for neonatal paediatric surgery for the Republic of Ireland. Our study consisted of 2 cohorts to examine for changes in the timing of diagnosis of ARM. Cohort A included cases from 1999 to 2009. This population was previously studied in 2010. Cohort B consisted of cases diagnosed between 2010 and 2012. Demographic and clinical data were recorded with particular attention to clinical presentation (clinical features suggestive of anorectal malformation, such as constipation, abdominal distension, bilious vomiting, sepsis, and failure to pass meconium), timing of diagnosis (given in hours of life), type of ARM (high vs low; rectourethral, anovestibular etc.) and any complications as a consequence of late diagnosis, such as perforation and sepsis. Delayed diagnosis was defined as diagnosis made after 48 hours of life. Data collection and statistical analysis were carried out using a statistical software package (Microsoft® Excel 2007).

Results

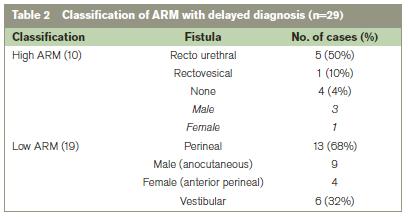

The medical records of 136 cases with a recorded diagnosis of ARM between 1999 and 2012 were reviewed in the study. The ratio of males to females was 1:1.7. The commonest symptoms at presentation were abdominal distension (58%), bilious vomiting (35%), delayed passage of meconium (19%), sepsis (14%), and constipation (14%). In total, 29 patients (21.3%) out of 136 had delayed diagnosis (Table 1). The age at diagnosis ranged from days 3 of life to 7 years with median age of day 4 of life. The delay in diagnosis led to large bowel perforation in 3 cases (10.3%). Ten patients (34.5%) had a high ARM with 17 patients (65.5%) having a low malformation (Table 2). Unfortunately there was no improvement in the rate of delayed diagnosis of ARM between the 2 cohorts (21.2% vs 21.6%).

Associated congenital anomalies

Patients from both cohorts who had delayed diagnosis had a high incidence of synchronous congenital anomalies. In cohort A only 4 (19%) cases had no associated anomalies, while none of those in cohort B were without an associated anomaly. Examples of encountered pathologies from cohort B included bilateral cleft lip (1 case), VSD/ASD (4 cases), tracheo-oesophageal fistula (1 case), and bilateral hydroureteronephrosis (1 case). Conversely, in this same cohort, 8 of 22 patients (36%) whose diagnoses were not delayed had no associated congenital anomaly.

Delayed diagnoses

An unusual case recorded involved a 7 year old girl with developmental delay and a history of perinatal hypoxic insult who was diagnosed following presentation with chronic constipation. She ultimately underwent a primary modified posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP). Another neonate was transferred on day 3 of life from a regional hospital with abdominal distension and suspected intestinal obstruction, having passed meconium and been documented to have a normal anus. Clinical assessment revealed an imperforate anus while examination of his x-rays from the transferring hospital showed the nasogastric tube was curled up in the upper oesophagus consistent with tracheo-oesophageal fistula/oesophageal atresia (TOF/OA). One neonate with a background of bilateral cleft lip was diagnosed at 4 weeks of age following an episode of urosepsis.

The proportion of patients whose initial surgical management following delayed diagnosis involved diverting colostomy formation was similar in both cohorts, with 11 patients (52.4%) in cohort A and 5 patients (62.5%) in cohort B being managed this way. Five patients (23.8%) in cohort A and 2 patients (25%) in cohort B underwent primary anoplasty. Four patients (19.1%) in cohort A and one aforementioned patient (12.5%) from cohort B were treated with a primary modified PSARP (mini-PSARP). One patient in cohort A (4.8%) was treated with primary diverting ileostomy due to gross large bowel dilatation and perforation of the sigmoid colon. No patient in either group underwent a primary PSARP.

Discussion

Anorectal malformations are a spectrum of conditions ranging from imperforate anal membrane to complete caudal regression4. Most of these anomalies can be easily identified by inspection of perineum during routine neonatal examination and immediate referral should be made to a tertiary care centre for appropriate management9,10. If the diagnosis of anorectal malformation is delayed, the child is likely to have a significantly higher incidence of serious complications with associated major stress to carers5. A study on Cohort A was published in 2009 which revealed that approximately 21% of all children presenting to a paediatric surgical tertiary referral centre had a delay in diagnosis of their ARM in excess of 48 hours, with an associated burden of morbidity including bowel perforation, which occurred in 2 patients (9.5%)8. The similar trend observed in cohort B (Table 1) is disappointing. One study of 52 consecutive cases of anorectal malformation found that rates of delayed diagnosis are approximately double this when 24 hours of life is used as the threshold for defining delayed diagnosis7. Of note the rate of bowel perforation in that study population, at approximately 10%, is similar to that recorded in our population. It appears somewhat fortunate that we have not experienced any mortality in either cohort when mortalities have been described in the setting of delayed diagnosis in other papers.

Nonetheless, widespread problems exist internationally regarding the diagnosis of anorectal malformations, something which is recognised in the literature7,11-13. One retrospective review of 75 cases, which used 24 hours of life as the threshold criterion for delayed diagnosis, suggests that this phenomenon is much more common than was previously thought while another review of 36 cases suggested the problem is particularly prevalent in the developing world5,14. A number of other congenital anomalies (cardiac, congenital cataracts and developmental dysplasia of hip) may be missed on routine neonatal check15,16. One aforementioned case in our study was transferred on the third day of life from regional hospital with not only a previously undiagnosed anorectal malformation but also an undiagnosed TOF/OA. However it could be argued that an ARM is a far less subtle congenital anomaly than congenital cardiac or hip pathology.

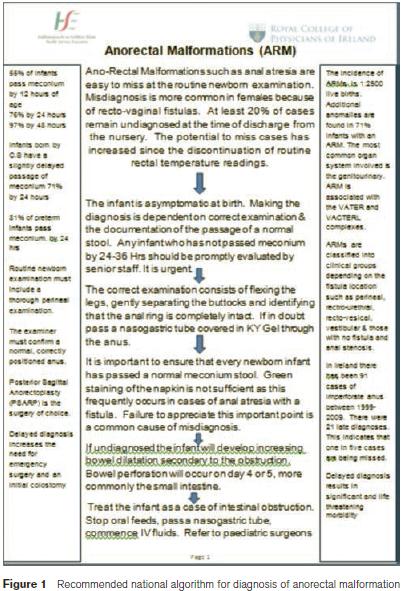

Current guidelines indicate that detailed examination for significant congenital anomalies should be performed by an appropriately trained clinician between 24 and 48 hours of birth17,18. The passage of meconium alone should not be taken as an indication of normal anal anatomy as meconium may also be passed via a fistula. Similarly, the presence of an anus does not exclude ARM8. We emphasize that the neonate should be fully undressed and the perianal area must be cleaned of meconium. Careful, comprehensive clinical examination of a baby should include documentation of the position, appearance and patency of the anus. The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI) has recently constructed an algorithm to aid in the diagnosis of anorectal malformations (Figure 1). We strongly recommend adherence to this algorithm to improve diagnosis of ARM, and improve the current unacceptably high rate of delayed diagnosis. At present in this country delayed diagnosis of ARM is a common occurrence and carries the risk of severe life-threatening complications in the short term, and increased morbidity in the longer term. This situation is unacceptable. Despite our previous study highlighting the issue, there has been no improvement in pick-up rates. Adherence to a clinical algorithm may be the only way to make delayed diagnosis of anorectal malformations the rarity it should be.

Correspondence: D Coyle

Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin 12

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Holschneider AM, Hutson JM. Anorectal malformations in children. 4th ed.,Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; 32

2. O’Neill J, Rowe MI, Grosfeld JL, Fonkalsrud EW, Coran AG. Paediatric surgery.5th ed, St Louis,Mosby,1998; 1425-48

3. Hall DM, Health for all Children. Oxford. OUP; 1996

4. Kim HLN, Gow KW, Penner JG, Blair GK, Murphy JJ, Webber EM. Presentation of low anorectal malformations beyond the neonatal period. Paediatrics2000;105:e68

5. Lindley RM, Shawis RN, Roberts JP. Delays in the diagnosis of anorectal malformations are common and significantly increase serious early complications. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95:364-8

6. Eltayeb AZ. Delayed presentation of anorectal malformations: The possible associated morbidity and mortality. Paediatr Surg Int 2010; 26:801-806

7. Haider N, Fisher R. Mortality and morbidity associated with late diagnosis of anorectal malformations in children. Surgeon 2007; 5:327-330

8. Turowski B, Dingemann J, Gillick.J. Delayed diagnosis of imperforate anus: an unacceptable morbidity. Pediatr Surg Int 2010; 26: 1083-1086.

9. Position statement of the Fetus and Newborn Committee of the Paediatric Society of New Zealand. Routine examination of the newborn. N Z Med J 2000; 113:361-3

10. Pena A. Management of anorectal malformations during the newborn period. World J Surg 1993; 17:385-92

11. Chakravartty S, Maitey K, Ghosh D, Choudhury CR, Das S. Successful management in neglected cases of adult anorectal malformation. Singapore Med J2009; 50:e280-2

12. Devdas D, Curry J. Don’t be fooled by meconium. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract 2009. Ed.92:ep135-8

13. Sinha S, Kanojia R, Wakhlu A, Rawat JD, Kureel SN, Tendon RK. Delayed presentation of anorectal malformation. J Indian Assoc Paediatr Surg 2008; 13:64-8

14. Sharma S, Gupta DK. Delayed presentation of anorectal malformation for definitive surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 2012; 28: 831-4

15. Mebeg A, Otterstad JE, Froland G et al. Early neonatal screening of neonates for congenital heart defects: the cases we miss. Cardiol Young 1999;9(2):169-174.

16. Jones D. Neonatal detection of developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH). J Bone Joint Surg 1998; 80:943-5

17. Moss GD, Cartilidge PH, Speidel BD, Chambers TL. Routine examination in the neonatal period. BMJ 1991; 302:878-9

18. Bloomfield L, Rogers C, Townsend J, Wolke D, Quist-Therson E. The quality of routine examinations of the newborn performed by midwives and SHOs; an evaluation using video recordings. J Med Screen 2003; 10:176-80