M O'Cathail, M O'Callaghan

Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

Abstract

Personal health practices are important determinants of health. Smoking habits are well documented among doctors. However, alcohol consumption, exercise rates and obesity rates are not. No indigenous studies have been done in this area. This descriptive population study aims to determine these factors. A questionnaire was sent to 381 consultants in hospitals affiliated with UCC Medical School. The response rate was 52.5% (200/381). The smoking rate was 7.5% (15/200) and the alcohol consumption rate was 94% (188/200). Both were more prevalent in females. Over a fifth took no exercise and activity levels were similar between groups. Female consultants were better at weight management than males with a lower proportion over the healthy body mass index (BMI) level. The smoking rate and alcohol consumption rate is higher than other studies. When compared to the general population, doctors are a healthier weight and smoke less but more consultants drink and less exercise regularly.

Introduction

One the best studies of lifestyle and health, spanning 50 years, is Doll and Peto’s “British doctors smoking study” published in 20041. It showed a high prevalence of smoking among doctors (85%) and follow up over 50 years documented the toxic effects of smoking. Today, we know that alcohol consumption, obesity and activity levels are also important aspects of a healthy lifestyle. Studies on smoking in doctors show smoking habits vary internationally. Low rates of current smokers were found in the USA (2%), Australia (3%) and the UK (3%). This is not universal however, in Greece and China rates are as high as 49%2. The Questionnaire Survey of Physical activity in General Practitioners (PHIT) study in Ulster reported GP’s smoking rates were much lower than the general population (4.2% v 29%; p< 0.001)3. Alcohol is causally related to more than 60 different medical conditions. It is estimated that 4% of the global burden of disease is attributable to alcohol, which accounts for about as much death and disability globally as tobacco and hypertension4. In Germany 90.5% of doctors drink alcohol. Binge drinking, defined as consuming more than 6 units per occasion, is prevalent (53%). Being male and having a surgical specialty were observed as risk factors for hazardous drinking5. The PHIT study found, more GP’s drink alcohol (86.5%) compared to the general population (71.6%) but fewer GPs reported drinking above recommended limits (12.6%) compared to the general population (16.9%)3.

Obesity is now one of the most significant health problems in the western world. It is estimated that, by 2030, there will be 11 million more obese adults in the UK than there are today. The combined medical cost associated with treatment of preventable diseases is expected to increase by £2 billion per year6. In Ireland today, 63% of people are overweight or obese7. Britain’s Chief Medical Officer stated that for general health 30 minutes a day of at least moderate intensity physical activity on five or more days of the week reduces the risk of premature death from cardiovascular disease, some cancers and type 2 diabetes8. But do doctors follow this advice? Studies from Britain and Canada found that GP’s do less exercise than teachers and the general population9,10. However, in Northern Ireland the PHIT GP studyfound that doctors had lower levels of inactivity (46.4%) than the general population (56.2%) and other professionals (51.8%)3. With this variation from country to country a study analysing the health practices of our indigenous medical profession is needed. This study aims to determine the patterns of smoking, alcohol consumption and exercise among consultants using a descriptive population study.

Methods

A review of the current literature was done using Pubmed, the Cochrane library and Google Scholar. An 18-point, anonymised, questionnaire with four separate sections on demographics, smoking habits, physical activity and alcohol usage was produced. The modified International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)11 was used as a tool to study exercise, as were questions from the Survey of lifestyle attitudes and Nutrition in Ireland study (SLAN) to assess alcohol usage12. The study was piloted on 10 Consultants in South Tipperary General Hospital. The study was begun in 2009 and data collection completed in early 2010. There were 381 consultants identified in nine acute hospitals in Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary which were affiliated with UCC Medical school. This sample is thus representative of consultants in Munster. A package was sent to each consultant comprising a covering letter explaining the purpose of the study, a reply envelope and a questionnaire. The questionnaire was tagged to avoid duplication. A deadline for survey completion was set after which a second questionnaire was sent to non-responders to improve the response rate. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS. The chi-square test was used for categorical data and the independent t-test was used for continuous data.

Results

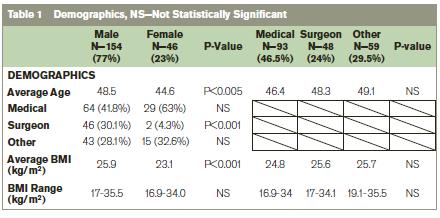

Of the 381 consultants surveyed 80.3% (306) were male and 19.7% (75) were female. The response rate was 52.5% (200/381 respondents), which was similar for all hospitals in the study. The response was higher among females than males 61.3% (46/75) vs 50.3% (154/306). The group ‘Other Specialists’ comprises a mixture of Obstetricians, Radiologists, Pathologists, Anaesthetists and Psychiatrists. The study demographics are outlined in Table 1. The average male consultant was 48.5 years old, weighs 82.9kg, is 1.79m in height and has a BMI of 25.9kg/m2. The average female consultant was 44.6 years old, weighs 64kg, is 1.67m in height and has a BMI of 23.1kg/m2. These represent statistically significant differences between male and female consultants in this population (p<0.001).

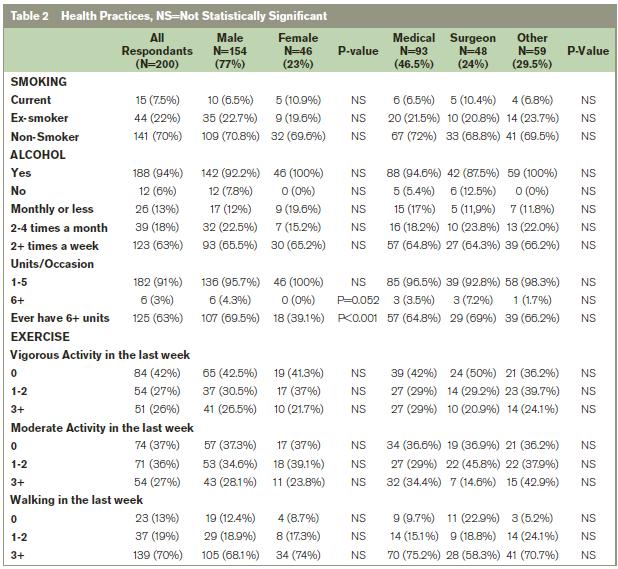

The current smoking rate was 7.5% overall with women and surgeons recording the highest rates at 10.9% and 10.4% respectively. Most consultants never smoked (70.5%) but over a fifth would categorise themselves as ex-smokers. A high proportion consumed alcohol (94%) with nearly two thirds doing so on at least 2 days a weeks. The vast majority consumed between 1 and 5 units per occasion (96.8%). A higher proportion of males than females admitted to binge drinking at least once in the preceding year (69.5% vs. 39.1%, p<0.001). Of those who admitted to binging in the previous 12 months, 68.3% did so on a less than monthly basis.

Consultants were asked to report their exercise from the previous week. Activity levels were divided into vigorous, moderate and walking. A list of activities was provided for each group to aid accurate reporting, as per the IPAQ questionnaire. Moderate activity was defined as 3 or more days of vigorous activity or 5 or more days of moderate-intensity activity of at least 20 minutes per day. On this basis, 33.5% of consultants had at least moderate activity levels. Over a fifth reported doing no form of regular physical activity (22%). Only 11.5% reported doing no exercise of any kind. Almost 70% of consultants reported taking a walk on 3 or more days that week. There were no significant differences in activity levels across the groups. From the self-reported weights and heights, it was possible to calculate the body mass index (BMI) of the consultants. Overweight was defined as a BMI between 25 and 29.9kg/m2 and obese was defined as a BMI >30kg/m2. More males than females were overweight (48.7% vs. 21.7%) and obese (9.1% vs. 2.2%) The results of the health practices section are summarised in Table 2.

Discussion

This study provides a unique insight into the health practices of consultants in Munster. This may be representative of consultants in Ireland as a whole, as hospitals in both urban and rural settings were included. Is it a case of “Do as I say but not as I do”? Many studies have shown that health care workers who smoke inadvertently undermine their roles in advising or assisting smokers to quit13-15. In 1983 a study found that 80% of US citizens expected their physicians to be non-smokers16. In 1984, Wells et al suggested that physicians with good personal health habits counselled their patients significantly more about all health habits17. These principles may be equally valid in other areas of healthy living. When trying to answer the question of whether doctors are good role models for their patients, it is important to look at the population that surround them. In Ireland, this information is easily extracted from the SLAN study, which is a population study encompassing the aspects of health covered in this study and many others. It is also important to compare, where possible, Irish consultants to their international peers.

The consultant smoking rate in this study was favourable when compared to the general population (7.5% vs. 29%)6 but was still higher than rates among doctors from the UK and Northern Ireland (7.5% vs. 3-4.2%)2,3. The high proportion of ex-smokers may represent the changing attitudes of doctors as evidence, such as Doll and Peto’s landmark trial, emerged about the health risks with smoking. As mentioned, 94% of consultants consume alcohol, which is higher than the national rate of 81%6 and is also higher than the peer rates reported in Northern Ireland (86.5%)3 and Germany (90.5%)4. The vast majority of consultants do not exceed 6 units when they drink alcohol. However, the proportion who admitted to binge drinking at least once in the preceding year was higher than reported in other physician studies (62.5% vs. 53%)4. As with other studies, male gender was highlighted as a significant risk factor for binge drinking. Rates for the general population were not reported for comparison.

The SLAN study found an overall pattern of higher levels of physical activity in younger men, reducing with increasing age, with a relatively low level of physical activity in women across all age groups6. This study found no difference in intensity or duration of physical activity between genders. The proportion of consultants who are categorised as at least moderately active is much lower than reported in the general population (33.5% vs. 71%)6. With obesity being a key target of public health groups, it is important that doctors lead by example. In this regard they do compare well with the general population, significantly fewer female consultants are overweight or obese (23.9% vs. 57%)6. By contrast a higher proportion of male consultants were overweight than males in the general population (48.7% vs. 45%)6. However a lower proportion of consultants are obese (9.1% vs. 24%)6. These results suggest that female consultants are more successful at maintaining a healthy BMI than their male colleagues.

Some caution should be taken when comparing these figures with other studies as questions may be phrased differently. While the IPAQ questionnaire and guidelines were used for physical activity there may have been differences in the collection method. Nevertheless, we can draw some conclusion from this survey. Smoking rates are low and compare favourably with the general population. However, peer studies in other countries show rates of half that seen among this population. The proportion that consumes alcohol is also higher both than the general population and than other international peer groups. While most consultants drink in moderation there is cause for concern with the self-reported binge-drinking rate again higher than rates from other studies on doctors. Consultants are not as active as the general population but seem to have better weight management with significantly lower rates of obesity being noted.

Therefore, this survey returns a mixed report on the state of the health practices of consultants. It has highlighted that some areas need more attention. Smoking rates are still too high and comparisons with international peers show just how much room for improvement there is. Exercise levels are too low; this may be a reflection of busy work schedules so perhaps work life balance needs to be addressed. If we are to truly advocate healthy living to our patients then we must endeavour to lead by example and, first, improve our own practices, otherwise we run the risk of undermining our own advice. At least in some instances it appears to be a case of “Do as I say, not as I do!”

Correspondence: M O'Cathail

Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I: Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004, 328:1519-1528

2. Smith DR, Leggat PA; An international review of tobacco smoking in the medical profession: 1974–2004, BMC Public Health 2007, 7:115

3. McGrady FP, McGlade KJ, Cupples ME, Tully MA, Hart N, Steele K. Questionnaire Survey of PHysical ActivITy in General Practice (PHIT GP Study) Ulster Med J. 2007;76:91–7.

4. Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and Public Health, Lancet, 2005 Feb 5-11;365:519-30

5. Rosta, J.; Hazardous alcohol use among hospital doctors in Germany, Oxford journals: Alcohol and Alcoholism 2008 43:198-203

6. Wang CY, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M, Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK (2011) The Lancet, 378, 815-825

7. Ward, M., McGee, H., Morgan, K., Van Lente, E., Layte, R., Barry, M., Watson, D., Shelley, E. and Perry, I. (2009) SLÁN 2007: Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition in Ireland. ‘One Island – One Lifestyle?’ Health and lifestyles in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland: Comparing the population surveys SLÁN 2007 and NIHSWS 2005, Department of Health and Children. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

8. Donaldson L.; At least five a week: evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. A report from the Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health; 2004.

9. Chambers R. Health and lifestyle of general practitioners and teachers. Occupational Medicine 1992; 42: 69-7

10. Gaertner PH, Firor WB, Edourd L. Physical inactivity among physicians. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1991; 144: 1253-7

11. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2003; 35: 1381-95.

12. SLÁN population study questionnaire 2006, Section E, Alcohol and other substances; Q E1-E3 & E5-E6

13. Adriaanse H, Van-Reek J, Physicians’ smoking and it’s exemplary effect. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1989; 7:193–196.

14. Joint committee on smoking and health of American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Asia Pacific Society of Respirology, Canadian Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Smoking And Health: A physician's responsibility. Eur Respir J 1995, 8:1808-1811

15. Chapman S: Doctors who smoke. BMJ 1995, 311:142-143

16. Sachs DP: Smoking habits of pulmonary physicians. N Engl J Med 1983, 309:799.

17. Wells KB, Lewis CE, Leake B, Ware JE Jr: Do physicians preach what they practice? A study of physicians' health habits and counselling practices. JAMA 1984, 252:2846-2848.