D Edgeworth, J Brohan, S O'Neill, M Maher, D Breen, D Murphy

Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

Abstract

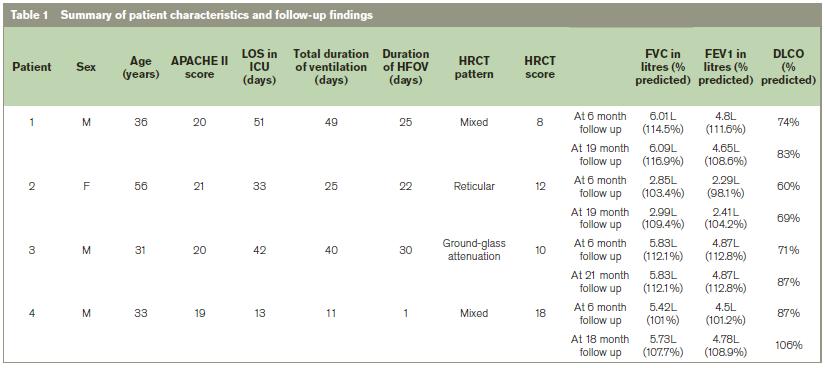

During the recent influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, due to severe respiratory failure many patients required treatment with alternative ventilator modalities including High Frequency Oscillatory Ventilation (HFOV). We present four such patients treated with HFOV at an academic, tertiary referral hospital in Ireland. We detail outcomes of clinical examination, pulmonary function testing, quality of life assessment and radiographic appearance on CT Thorax at follow-up at 6 months. Further clinical assessment and pulmonary function testing were performed at median 19months (range 18-21 months) post-discharge. At initial review all patients were found to have reduced gas transfer (median predicted DLCO 74%) with preservation of lung volumes and normal spirometrical values at 6 months (median FVC 5.42L[101% predicted] and FEV14.5L[101.2% predicted] respectively), with improvements in gas transfer (median predicted DLCO 83%)at subsequent testing. Post-inflammatory changes on CT thorax at 6 months were seen in all 4 cases. To our knowledge this is the first report to document the long-term effects of severe H1N1 infection requiring high frequency oscillation on respiratory function. We conclude that the effects on respiratory function and pulmonary radiological appearance are similar to those observed following conventional treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [ARDS].

Introduction

In the management of ARDS the use of ‘Rescue therapies’ including high frequency oscillatory ventilation [HFOV] and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO] are generally reserved for patients refractory to conventional ventilation. In this series of four patients with H1N1 infection requiring HFOV, we investigate outcome at six months, on PFTs and radiological appearance on CT, with further follow up of PFTs at mean 19.25 months following discharge.

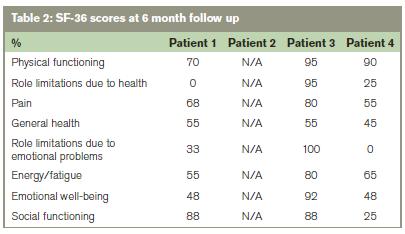

Six month follow up included physical examination, resting oxygen saturation measurement, quality of life assessment using Short Form 36(SF-36), PFTs and 64-slice CT scan. Evaluation at mean 19.25 months consisted of clinical assessment, resting oxygen saturation measurement and PFTs. PFTs were measured in accordance with international guidelines1.

Similar methodology for grading CT thorax findings as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) studies was used2,3. We classified the predominant CT pattern as: normal attenuation; consolidation; ground- glass opacification (hazy areas of increased attenuation without obscuration of the underlying vessels); [mixed pattern (combination of consolidation, ground glass opacities and reticular opacities in the presence of architectural distortion); ground glass attenuation with traction bronchiectasis; or honeycomb pattern. The extent of disease was quantified by dividing each lung into three zones: upper (above the carina), middle (below the carina but above the inferior pulmonary vein), and lower (below the inferior pulmonary vein). Each zone was assigned a score: 1 when <25% involvement, 2 when 25-50% involvement, 3 when 50-75% involvement, and 4 when >75% involvement. The total of all 6 zones was recorded, with a maximal possible score of 24. Assessment was in consensus by two radiologists, blinded to the patients’ clinical information.

Case 1

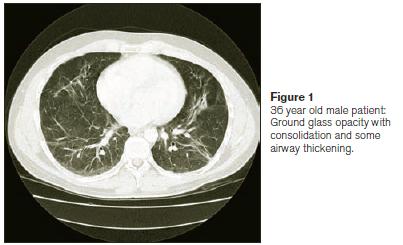

A 36-year-old male smoker presented febrile, tachypnoeic and agitated in mild type 1 respiratory failure. Chest x-ray showed bilateral infiltrates. Sputum cultured streptococcus pneumoniae for which ceftriaxone was commenced. Following positive H1N1 screen oseltamavir was commenced. His condition however, deteriorated rapidly requiring full ventilator support. CT thorax performed on day nine of ICU admission demonstrated bilateral infiltrates with right lower lobe consolidation. Bronchoscopy demonstrated normal proximal airways with minimal secretions to sub-segmental level. Due to worsening respiratory status on day 10 HFOV was commenced. A right-sided pneumothorax developed on day 4 of HFOV requiring chest drain insertion. He gradually improved and after a 51 day ICU admission was transferred to a general respiratory ward for a period of intensive rehabilitation prior to discharge. At review six months later, CT thorax showed residual scarring in both lungs, particularly at the apices and left upper lobe anteriorly with interval resolution of small pneumatocoeles. Findings were predominantly consolidative, ground glass and reticular. CT score was 8/24 (Figure 1, Table 1). SF-36 demonstrated moderate limitation in physical and mental wellbeing (Table 2). PFTs demonstrated a mild decrease in DLCO, with improvement on follow-up testing (Table 1). Resting oxygen saturations were normal at both follow-up assessments.

Case 2

A 56-year-old female non-smoker with breast carcinoma presented with a 2-day history of non-productive cough, breathlessness and fever. Three cycles off luorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide had been completed three months prior to presentation. The patient was pyrexial and in respiratory failure. Chest x-ray demonstrated bi-basal consolidation. H1N1polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive. Piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin and oseltamivir were commenced. Non-invasive ventilation was well tolerated initially but the patient deteriorated requiring intubation and HFOV. HFOV was continued for 22 days. She suffered severe critical illness neuromyopathy but following intensive physiotherapy was ultimately discharged home well. At six-month follow-up she had moderate impairment in DLCO with normal spirometry. Resting oxygen saturations were normal. CT thorax revealed post-inflammatory changes with a predominantly reticular pattern and CT score was 12/24. Her DLCO showed interval improvement at 19 months (Table 1). Unfortunately SF-36 data is not available.

Case 3

A 31 year old non-smoking male was admitted to another hospital with abdominal pain requiring open appendicectomy. He developed post-operative respiratory failure and CXR revealed extensive bilateral consolidation. He was intubated but responded poorly to conventional ventilation and was transferred to our centre for HFOV. H1N1 PCR was positive. He received teicoplanin, metronidazole, fluconazole, oseltamivir and ciprofloxacin. On day 21he developed bilateral pneumothoraces requiring chest drain insertion. HFOV was required for 30 days in total. The patient made a dramatic recovery and was discharged home 13 days later. CT thorax at 6 months showed predominantly ground-glass changes with CT score 10/24.Resting oxygen saturations were normal. SF-36 demonstrated moderate limitations in physical, social and emotional wellbeing (Table 2). Follow-up PFTs demonstrated mild impairment in DLCO which had improved at 21 months (Table 1).

Case 4

A 33-year-old male presented with flu-like illness and respiratory failure. He had well-controlled asthma requiring intermittent salbutamol treatment only. He was intubated and commenced on HFOV. Chest x-ray demonstrated bilateral consolidation with effusions. H1N1 PCR was positive. Clarithromycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin and oseltamivir were commenced. Following ten days the patient was extubated to non-invasive ventilation. Due to on-going hypoxia a CTPA was performed, which demonstrated lower lobe pulmonary emboli for which he was anti-coagulated. Following rehabilitation at ward level the patient was discharged. At six months DLCO was 87% predicted, with spirometry within normal limits. Resting oxygen saturations were normal. CT demonstrated mild linear fibrotic changes bilaterally, most marked in the left upper lobe. CT score was 18/24. SF-36data demonstrated poor functioning in role limitation and social functioning (Table 2). At 18-month follow up, interval improvement in PFTS was noted (Table 1).

Discussion

Recent publications describe characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe H1N1 infection treated in the ICU setting. Patients deemed high risk were aged less than 5 or greater than 65 years of age, pregnant, obese or had pre-existing medical conditions4-7. The use of therapy such as HFOV is generally reserved for ARDs patients who fail conventional treatment. In this study we present four cases of severe H1N1 infection requiring HFOV. Mean HFOV duration was 19 days with a mean ICU stay of 35 days. Two of four patients developed pneumothoraces with bilateral pneumothoraces in one case. Average age was 40 years, and ¾ patients were male (Table 1). The respiratory and neuropsychological sequelae post-ARDs are well documented8,9. In our cohort, despite the necessity for HFOV spirometry was normal at 6months. DLCO was however low, with mean 73% predicted at 6 months and mean 86% predicted at median 19.25 months follow-up. In a previous study following ARDS survivors

FEV1 and FVC normalised at 6 months while DLCO remained low8. More recently a five-year follow up of ARDS survivors has demonstrated similar, mild impairment in DLCO at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years9. Our findings are consistent with these. A previous report documenting HRCT and BAL findings of 12 patients post- SARS reported persistent CT changes at 90 days8. In our cohort, persistent CT changes were noted in all patients, characterised as mixed pattern, which were predominantly reticular, and ground glass in nature. The Short Form 36 Questionnaire (SF-36) is a validated assessment tool utilised to monitor and compare disease burden11. It determines current quality of life as a percentage of that one-year ago. Herridge et al previously demonstrated poor functioning in the physical domains in ARDS survivors with improvements physical functioning, role and social functioning scores at 1 year follow up8.

In conclusion, by 6 months, despite the necessity for prolonged ventilation, FVC and FEV1 were in the normal range but DLCO was reduced in all subjects. There was radiological evidence of mild, persistent pulmonary parenchymal abnormality characterised as predominantly ground glass and reticular in nature. Repeat PFTs at mean 19.25 months showed interval improvement in DLCO. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of patient follow up which focuses specifically on those who required HFOV for treatment of ARDS due to H1N1 infection.

Correspondence: D Edgeworth

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Lacroix J, Stelfox T, Bagshaw S, Choong K, Lamontagne F, Turgeon AF, Lapinsky S, Ahern SP, Smith O, Siddiqui F, Jouvet P, Khwaja K, McIntyre L, Menon K, Hutchinson J, Hornstein D, joffe A, Lauzier F, Singh J, Karachi T, Wiebe K, Olafson K, Ramsey C, Sharma S, Dodek P, Meade M, Fowler RA. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA. 2009 Nov 4;302:1872-9.

2. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Miller MR, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Wanger J. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005 Nov;26:948-68.

3. Ooi GC, Khong PL, Muller NL, Yiu WC, Zhou LJ, Ho JC, Lam B, Nicolaou S, Tsang KW. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004 Mar;230:836-44.

4. Wang CH, Liu CY, Wan YL, Chou CL, Huang KH, Lin HC, Lin SM, Lin TY, Chung KF, Kuo HP. Persistence of lung inflammation and lung cytokines with high-resolution CT abnormalities during recovery from SARS. Respir Res.2005; 6:42.

5. Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Harper SA, Shaw M, Uyeki TM, Zaki SR, Hayden FG, Hui DS, Ketter JD, Kumar A, Lin M, Shindo N, Penn C, Nicholson KG. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 6;362:1708-19.

6. Dominguez-Cherit G, Lapinsky SE, Macias AE, Pinto R, Espinosa-Perez L, de la Torre A, Poblano-Morales M, Baltazar-Torres JA, Bautista E, Martinez MA Rivero E, Valdez R, Ruiz-Palacios G, Hernadez M, Stewart TE, Fowler RA. Critically Ill patients with2009 influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. JAMA. 2009 Nov 4;302:1880-7.

7. Miller RR, 3rd, Markewitz BA, Rolfs RT, Brown SM, Dascomb KK, Grissom CK, Friedrichs MD, Mayer J, Hirshberg EL, Conklin J, Paine R 3rd, Dean NC. Clinical findings and demographic factors associated with ICU admission in Utah due to novel 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection. Chest. 2010 Apr;137:752-8.

8. Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, Cooper AB, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Barr A, Cook D, Slutsky AS. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003 20;348:683-93.

9. Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Kudlow P, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Cheung AM. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011 Apr 7;364:1293-304.

10. Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 20;353:85-93.

11. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss M, McHorney WH, Raczek A. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre; 1994