|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lucy Balding

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2013 Apr;106(4):122-4

L Balding

Our Lady's Hospice and Care Services, Harold's Cross, Dublin 6W

Abstract

Pain is the single most common reason why patients seek medical care. Worldwide, there are 10 million new cases of cancer each year, with 6 million deaths annually. The World Health Organisation (WHO) first published Cancer Pain Relief in 1986, designed to be a simple, intuitive and accessible guide to the management of cancer pain that would be applicable and useful whatever the language, culture, economy, country and clinical setting. In Ireland today, we have ready access to many different opioids, and the WHO guidelines may seem inadequate and outdated. This article describes the evolution and use of the WHO guidelines, as viewed from the global perspective of its 193 member nations. The WHO ladder still remains valid today in Ireland, even as we await the imminent publication of new evidence-based national cancer pain guidelines this year.

|

|

Introduction

Worldwide, 10 million new cases of cancer occur each year, with 6 million deaths annually1. The World Health Organisation (WHO) Cancer Control Programme estimates that by 2020 this number will double, with 70% of cancer deaths occurring in developing countries, where most patients are diagnosed with late stage disease. Estimates reveal that 80% of terminal stage patients have no access to the analgesics they need2. In Ireland, an annual average of 29,745 cancer cases was registered during the three year period 2007-20093. Our cancer and palliative care services are well-developed and we have ready access to many analgesics. Viewed from a purely Irish perspective, the WHO cancer pain guidelines may seem invalid and outdated. On the eve of the publication of new Irish national cancer pain guidelines this year, we review the critical role of the WHO guidelines in shaping cancer pain management.

Historical perspective

At the turn of the last century, newly developed surgical techniques, improved radiation technology and the emergence of the biomedical science field of oncology fuelled the nascent hope of finding a cure for cancer4. The prevailing cultural concept of the time viewed “suffering at the end of life as a spiritual or existential test of character”. Pain was seen as an indicator of disease rather than a symptom worthy of treatment in its own right, whereas opioids were dismissed as the modality of last resort. Concerns over societal effects from opium dependence date as far back as 19th century Asia and the first Opium Convention was signed in The Hague in 1912. International and governmental policy since that time has chiefly related to drug control legislation and restriction of opioid supply, rather than recognition of the beneficial effects for patients in pain2. In tandem with increasingly restrictive legislature, deep societal concerns over narcotic addiction were increasing, both amongst the general public and amongst health professionals. Doctors began to prescribe opioids less and less, becoming de-skilled in their use, whilst a mystification arose around opioids themselves, not least the widespread belief that morphine hastens death.

During the 1950s, Raymond Houde, later joined by Kathleen Foley, began pioneering work assessing analgesic effectiveness4,5, whilst in Washington John Bonica’s early work culminated in the publication of the first modern textbook of pain medicine in 19536. In parallel, the work of Cicely Saunders in establishing the foundations of palliative care and the modern hospice movement was a critical element in highlighting cancer pain internationally as a public health problem. In 1982, at a time of changing societal attitudes towards the rights of the individual and the nature of suffering, Jan Stjernsward, head of the WHO’s Cancer Unit, invited leading figures to a meeting in Milan, with the brief of developing a new global policy on cancer pain relief.

Cancer Pain Relief, 1986

All agreed the WHO recommendations had to be clearly understandable. A ‘simple yet effective scheme’ was planned and Cancer Pain Relief (CPR) was published in 1986 (the current second edition followed in 19967). The booklet was translated into 22 languages8 and has had significant clinical and educational impact across the globe9. The five fundamental tenets of the guideline are well-known: ‘by the mouth’, ‘by the clock’, ‘by the ladder’, ‘for the individual’ and ‘attention to detail’. However, CPR provides much more than this simple guidance – in its 63 pages, it details an analysis of the causes of pain and guidance on the proper evaluation of pain. Whilst including discussion of non-drug measures and anti-cancer therapies, it emphasises that drug treatment is the mainstay of cancer pain management. A ‘basic drug list for cancer pain relief’ is provided, followed by a detailed discussion of the various recommended opioid and adjuvant drugs (including pharmacokinetics and side effect profiles).

The global consumption of morphine for medical purposes increased following publication of CPR in 19861. Morphine is included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines10 and is more readily and cheaply available in developing countries11. It was chosen by the WHO as the strong opioid of choice and remains the gold standard against which all other drugs are assessed. Comparative studies looking at morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, buprenorphine, fentanyl and methadone to determine which, if any, is superior are lacking. Newer drugs and drug formulations, such as modified release preparations, many transdermal patches, and rapid release fentanyl preparations are not included in the current edition of CPR, which has been criticised for not catering for those who are intolerant of opioids, those who suffer from complex pain, or incident pain, and those who don’t respond to conventional drugs. CPR by design is simple, thereby enabling flexibility. It is a framework of principles rather than a rigid protocol. For those few countries who have ready access to many different opioids, the WHO guidelines may indeed seem inadequate, but viewed from the global perspective of its 193 member nations, it works. Where greater guidance is required, recommendations such as the 2012 European Association for Palliative Care guidelines12 are readily available.

Opioid accessibility and cost

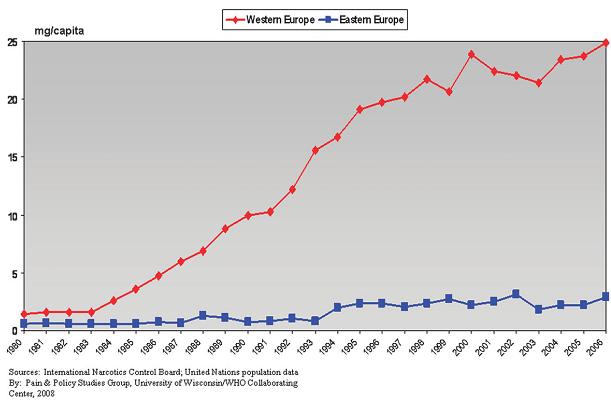

Narcotics are subject to both international and domestic controls. The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 supports the use of narcotics as indispensable for the relief of pain and suffering, and regulates their production, manufacture, import, export and distribution. Yet great disparity exists worldwide. Fears about opioid diversion, addiction and abuse continue to shape policy in some developed countries. Overregulation by excessively zealous restrictions, designed to restrict the diversion of opioids into illicit markets, has profoundly affected the availability of medicines for patients in pain, through creating such logistical obstacles to procurement as to produce a disincentive to the prescription of opioids at all. Examples include prescription limits, dose limits and permit requirements. Fear of regulatory scrutiny has been shown to impact on physicians’ decisions about opioid use13. Illogical prescribing restrictions exist in some jurisdictions, such as opioid availability for post operative pain, but not cancer pain, or for adults but not children9. Across Europe, access to opioids varies considerably, with a marked East/West divide14 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: East versus West Europe: morphine consumption, average milligram per capita*, 1980–2006. *Average milligram per capita calculated by adding milligram per capita statistic for each country and dividing by the total number of countries.

Happily, increased emphasis on statutory responsibility and clinical competence for doctors –namely, a legal framework to support relief of pain- is proving a useful foundation15. A number of negligence cases have been successfully brought against doctors who under-treated pain in the US9. In 1998, the All India Lawyers Forum successfully filed a public interest suit in the Delhi High Court requesting state governments to simplify the procedures for the supply of morphine to patients. In response to difficulty accessing opioids for palliative care patients in Uganda, (where a doctor to patient ratio of 1:18 000-50 000 exists) the Minister for Health in 2004 made a regulation authorizing trained palliative care nurses to prescribe narcotic analgesics.

The cost of opioids is a central factor. Generic oral immediate release morphine is the most cost-effective analgesia, and a week’s supply can cost as little as loaf of bread, or one US cent per 10mg. The cost to developing nations of commercially marketed modified release preparations or synthetic opioids are exorbitant, yet pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to provide oral immediate release morphine, as the profit obtained is minimal. Many nations cannot access affordable generic morphine, thus needing to produce their own supply domestically, or import expensive alternative opioids11.

Discussion

The WHO guidelines, by their very definition as laid out 25 years ago, were designed as a global template which could be followed in any setting, in any nation, inexpensively and simply, whatever be the local language, culture or healthcare system and they have been very successful in their aims. However, different countries apply the WHO guidelines differently, depending on drug availability –without access to opioids the ladder remains useless. In some developed countries, like Ireland, with ready opioid availability and established palliative care programs, the guidelines have been seen as outdated and of limited validity in contemporary practice. I believe that the fundamental role that the guidelines should play, and have played, in the promotion of global change in pain policy and, centrally, in the support of improved access to opioid analgesics is the crucial consideration. Their clarity, unambiguity and flexibility, crystallized by the iconic ‘clock’ and ‘ladder’ imagery, have been successfully embraced across the globe, resulting in improved pain control for countless patients with end stage cancer. Long may they continue to do so.

Correspondence: L Balding

Our Lady's Hospice and Care Services, Harold's Cross, Dublin 6W

Email: [email protected]

References

1. World Health Organisation. Narcotics and Psychotropic Drugs: Achieving balance in national opioids control policy -guidelines for assessment. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

2. Scholten W, Nygren-Krug H, Zucker H. The World Health Organization Paves the Way for Action to Free People from the Shackles of Pain. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2007;105:1-4.

3. National Cancer Registry of Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 2011: Annual report of the National Cancer Registry. Cork; 2011.

4. Seymour J, Clark D, Winslow M. Pain and palliative care: the emergence of new specialties. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:2-13.

5. Meldrum M. The ladder and the clock: cancer pain and public policy at the end of the twentieth century. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:41-54.

6. Bonica J. The management of pain: with special emphasis on the use of analgesic blocks in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. London: Henry Kimpton; 1953.

7. World Health Organisation. Cancer Pain Relief. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

8. Mair J. Is the WHO analgesic ladder active or archaic? European Journal of Palliative Care 2008;15:162-5.

9. Brennan F, Carr D, Cousins M. Pain Management: A Fundamental Human Right. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2007;105:205-21.

10. World Health Organisation. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. 15th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

11. Rajagopal M, Mazza D, Lipman A. Pain and Palliative Care in the Developing World and Marginalised Populations: a global challenge. Binghamton, New York: The Haworth Medical Press; 2003.

12. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N, Dale O, De Conno F, Fallon M, Hanna M, Haugen DF, Juhl G, King S, Klepstad P, Laugsand EA, Maltoni M, Mercadante S, Nabal M, Pigni A, Radbruch L, Reid C, Sjogren P, Stone PC, Tassinari D, Zeppetella G. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. The Lancet Oncology 2012;13:e58-e68.

13. Fishman S. Recognizing Pain Management as a Human Right: A First Step. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2007;105.

14. Cherny NI, Baselga J, de Conno F, Radbruch L. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Europe: a report from the ESMO/EAPC Opioid Policy Initiative. Annals of Oncology 2010;21:615-26.

15. Johnson S. Legal and Ethical Perspectives on Pain Management. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2007;105:5-7.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|