K Meghen1, C Sweeney2, C Linehan3, S O`Flynn2, G Boylan4

1St James’s Hospital, James’s St, Dublin 8

2School of Medicine, 3Department of Marketing and Management, and 4Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, UCC, Cork

Abstract

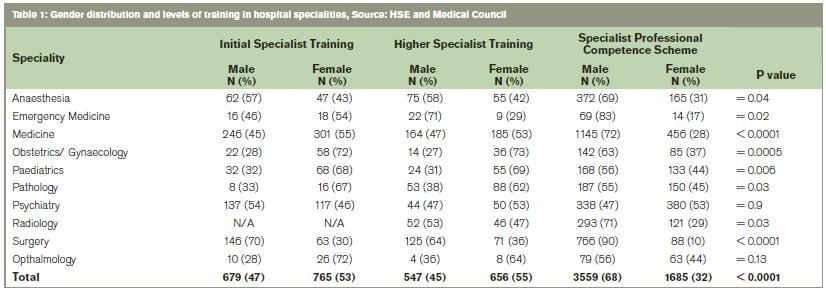

Although females represent a high proportion of medical graduates, women are under represented at consultant level in many hospital specialties. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were undertaken which established female representation at all levels of the medical workforce in Ireland in 2011 and documented the personal experiences of a sample of female specialists. The proportions of female trainees at initial and higher specialist training levels are 765(53%) and 656(55%) respectively but falls to 1,685(32%) at hospital specialist level (p< 0.0001). Significantly fewer women are found at specialist as compared to training levels in anaesthesia (p = 0.04), emergency medicine (p = 0.02), medicine (p < 0.0001), obstetrics/gynaecology (p = 0.0005), paediatrics (p = 0.006), pathology p = 0.03) and surgery (p < 0.0001). The lowest proportion of female doctors at specialist level exists in the combined surgical specialties 88(10%); the highest is in psychiatry 380(53%). Qualitative findings indicate that females who complete specialist training are wary of pursuing either flexible training or part time work options and experience discrimination at a number of levels. They appear to be resilient to this and tolerate it. Balancing motherhood and work commitments is the biggest challenge faced by female doctors with children and causes some to change career pathways.

Introduction

Medicine was once a male-dominated profession reflecting the male preponderance in medical schools. Subsequently an increase in female undergraduate entry has led to an even gender balance or slight female dominance in medical schools.1 Decades later, the effects of this changing demographic at undergraduate level should be evident at senior clinical and academic levels. This has not happened, fuelling speculation about possible barriers and discrimination.2 An alternative explanation is that work practices could explain this disparity as women are more likely to have worked part time and this might influence career trajectory.3 Women have similar motivations entering medical school, perform equally on an academic level and yet are more likely to change career choice than men both as undergraduates and during postgraduate training.4-8 Qualitative research may assist in improving understanding of the issues that influence carer choices in female doctors.

The career progression of women in academic medicine has received particular scrutiny in the US with convincing data to suggest that women are less recognised for their work.9-11 Women academics report experiencing gender-based bias or harassment.12 Women occupied 15% of full academic medical chairs in the US in 200513 and account for 12% of UK medical professors. Evaluation of promotion trends suggests “some workforce practices may be detrimental to women’s careers.”14,15 There is a scarcity of relevant published data from Ireland. Our aim was to capture female representation at all levels of medicine and to establish, by interviewing women consultants, factors influencing career choice and progression.

Methods

Medical undergraduate data were obtained from the Central Applications Office and the Higher Education Authority. Gender ratios of non-consultant hospital doctors (NCHDs) were obtained from the Health Services Executive. Gender distribution of hospital consultants is not readily available from any source. The Medical Council provided information on numbers and gender distribution of doctors enrolled in the specialist divisions of professional competence schemes. Clinical academic staff data was sought individually through contact with each of the medical schools in the country. Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions of females in common hospital specialties at NCHD and specialist levels. Female hospital consultants affiliated with the Medical School in University College Cork were identified and a random sample across specialities and age groups were invited to participate. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by a single researcher. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded, assigned numbers to protect anonymity and analysed independently by 3 researchers. An inductive strategy through open and selective coding was used to derive the predominant themes.

Results

Quantitative data

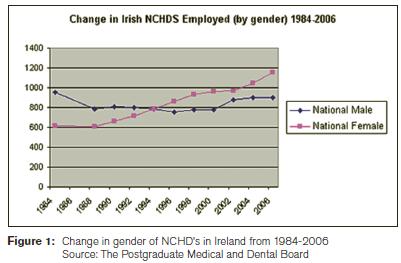

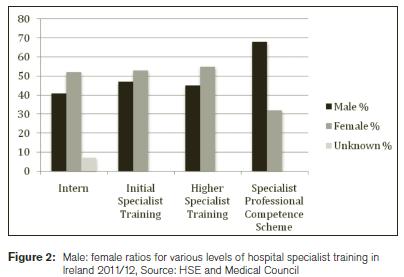

In the mid 1990s the gender balance of NCHDs changed from a majority of males to females (Figure 1). Females represent the majority of medical school entrants in Ireland over the last few decades.Sixty percent of successful medical school applicants were female in 2008. This trend was transiently reversed in 2009 with a near 50:50 gender distribution and reverted to 60:40 in favour of females again in 2010. There is a corresponding predominance in the early stages of hospital specialist training, however women are a significant minority in hospital specialist professional competence schemes (Table 1 and Figure 2). Table 1 summarises gender distribution by specialty and level of training. Women predominate at training levels in paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, and pathology (mirroring UK trends).16 Females are underrepresented in the surgical specialities. Women represent 17.5% (17/97) clinical professors in Ireland and 73% of senior lecturers (30/41).

Qualitative data

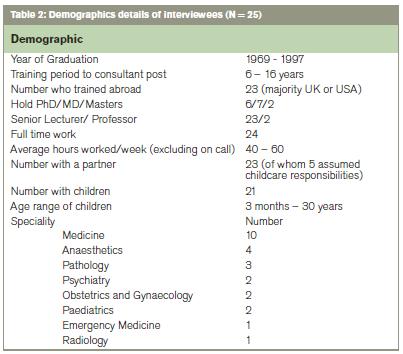

Twenty-five of the 32 (78%) women invited agreed to participate. Participant demographics are outlined in Table 2. Six themes arose from analysis of the interviews: career choice and training, support needed, discrimination, challenges at work, work life balance and changing practices in medicine.

Career choice and training

The majority of interviewees 22/25 gave interest as their main and often only reason for choosing their speciality. Travel necessary to complete training was a focus in all interviews with 23/25 having trained outside of Ireland. This caused a particular strain on relationships and was felt to have caused colleagues to exit from hospital and academic life. The vast majority 24/25 advocated part-time training but none had pursued this option, as it was perceived to have adverse career implications.

Support needed

No one wanted special consideration because they were female and this line of questioning often drew a strong reaction. The consensus was that people should be employed on merit. Supports became critical when children arrived and the absence of these marked career decline. Five of the interviewees had husbands or partners who were either full-time house-husbands or who only occasionally worked and two had parents who had relocated to assist with childcare.

Discrimination

This was a particularly interesting aspect of all interviews. Four described overt discrimination at interview. They acknowledged that legislation probably prevented such incidents now and events described occurred a decade previously. Others noted that “subtle” questions are asked about your family plans at interview and had no issue with this. Twelve participants described appraisal experiences that were specifically discriminatory. There was evidence of discrimination from other healthcare staff with descriptions of discrimination from more junior male doctors and nurses. Almost one third of the participants had encountered bias from patients. For some was a tendency to become “masculine” so as not to invite discrimination. Others acknowledged having to work harder to compensate for being a woman.

Challenges succeeding at work

Motherhood was the common denominator to most of the difficulties encountered by participants. Issues included maternity leave, problems with travel and less time for research. All who had children noted that “time-out” rapidly became the focus in interviews and consequently all had carefully limited this and ensured their CVs were “full”. Mothers and childless interviewees seemed equally aware of this phenomenon. Some had delayed starting a family until career security was attained.

Changing practices in medicine

The majority (22/25) of interviewees saw more job sharing and part time work as the mechanism to retain women. Some noted that flexible work practices would benefit both genders in medicine.

Work-life balance

All of the childless and single women interviewed were satisfied with their work life balance although one noted the strains of juggling academic and clinical work. The majority of mothers 17/21 were dissatisfied and felt expectations of them were unrealistic and colleagues assumed they should just make the necessary commitments. Sacrifices were made by all mothers to deliver at work and their children were considered to have suffered. Older mothers expressed bitter regrets and three had dissuaded their daughters from pursuing a career in hospital medicine.

Discussion

This is the first study for decades to document womens participation in hospital and academic clinical medicine in Ireland. We are the first to analyse qualitative data evaluating career choices, training obstacles and factors affecting progression of women in hospital clinical and academic medicine in Ireland. Our data suggest that the leaky pipeline in medicine persists and warrants ongoing monitoring and investigation. Policy makers and those with a responsibility for higher specialist training must evaluate and address the issues raised. This is especially pertinent at a time when the impacts of a potential manpower crisis and the NCHD exodus from hospital medicine are receiving such attention.17

There are several limitations to the data presented. Protracted training paths and career progression in hospital and academic medicine means that the quantitative data represents events of a previous decade. Summary statistics suggest females are well represented at initial and higher specialist training level in many specialties. However, there appears to be a deficit at specialist level with a greater than 2:1 ratio of males to females. Some of this may be due to the age profile of specialists with a significant proportion having trained when there was a majority of males graduating. However, women have been in the majority at NCHD level for almost 2 decades and the degree of continuing discrepancy between males and females at more senior levels is surprising. In addition, women have not substantially ascended to professorial positions in academic medicine. Women are well represented at senior lecturer level and may be clustered here if we note the findings from research elsewhere.18,19

Lifestyle does not appear to have influenced career choices at the outset but the uncertainty associated with travel and inflexibility in training and work especially when juggling motherhood leads to career changes. Few have had a negotiable training plan at the outset or defined travel expectations and this would seem to be an issue that is resolvable. There is little point in flexible training or working options if the prevailing perception is that pursuing these is equivalent to career suicide. The view held by some senior consultants that part time work options are evidence of lack of true commitment to the profession need to be addressed.20,21 This will influence training choices until evidence emerges that part-time training will not be a disadvantage. Equally the time-out issue needs to be addressed pragmatically. Motherhood is perceived as a career impediment and sadly evidence supports this.22

Those who have attained their desired career end-point were resilient to discrimination from any quarter and may even tolerate it. Perhaps, in order to survive and progress, they have learnt to accept practices and behaviours which they may initially have rejected. Bearing in mind that our sample is comprised of women who have stayed in the profession, these factors may be more pronounced for those who chose to leave. It is interesting that independent coding rather than interviewees revealed this theme. It is concerning that some accept the need to “compensate” for being female by being more productive than their male counterparts. Extreme examples of aberrant conduct in interviews and reviews may be historic but subtle versions of such practices appear to be pervasive. Perceptions of discrimination are not uncommon and are often tolerated especially by females in male dominated clinical specialties but the reported prevalence is usually low.12,23 Our data would suggest that perceptions of discrimination such as would be recorded by questionnaires may under-report its prevalence and reinforces the need for qualitative research, which is more likely to capture actual discrimination. Female nurses appear to treat female doctors differently and this needs further evaluation.

Our participants agreed that women must be committed to achieve their career goals but hoped that in future women would not have to make the sacrifices that they did. What is most striking perhaps is the overwhelming regrets some of the mothers expressed at the sacrifices they had made in relation to their children in order to achieve their career goals.

Correspondence: C Sweeney

UCC School of Medicine, Brookfield Health Sciences Complex, College Road, Cork Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

All the women who participated in this study for their generosity and honesty.

References

1. The demography of medical schools : a discussion paper. 2004, London: BMA. vi, 86

2. McManus, I.C. and K.A. Sproston, Women in hospital medicine in the United Kingdom: glass ceiling, preference, prejudice or cohort effect? J Epidemiol Community Health, 2000. 54: 10-6.

3. Taylor, K.S., T.W. Lambert, and M.J. Goldacre, Career progression and destinations, comparing men and women in the NHS: postal questionnaire surveys. BMJ, 2009. 338: b1735.

4. Hauer, K.E., Durning S.J., Kernan W.N., Fagan M.J., Mintz M., O'Sullivan P.S., Battistone M., DeFer T., Elnicki M., Harrell H., Reddy S., Boscardin C.K., Schwartz M.D.Factors associated with medical students' career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA, 2008. 300: 1154-64.

5. Rosenthal, M.P., Diamond J.J., Rabinowitz H.K., Bauer L.C., Jones R.L., Kearl G.W., Kelly R.B., Sheets K.J., Jaffe A., Jonas A.P., Ruffin M.T. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students' decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA, 1994. 271: 914-7.

6. Poole, P., K. McHardy, and A. Janssen, General physicians: born or made? The use of a tracking database to answer medical workforce questions. Intern Med J, 2009. 39: 447-52.

7. Edwards, C., Lambert T.W., Goldacre M.J., Parkhouse J. Early medical career choices and eventual careers. Med Educ, 1997. 31: 237-42.

8. Lambert, T.W. and M.J. Goldacre, Career destinations and views in 1998 of the doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1993. Med Educ, 2002. 36: 193-8.

9. Carr, P.L., Friedman R.H., Moskowitz M.A., Kazis L.E. Comparing the status of women and men in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med, 1993. 119: 908-13.

10. Ash, A.S., Carr P.L., Goldstein R., Friedman R.H.. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med, 2004. 141: 205-12.

11. Kaplan, S.H., Sullivan L.M., Dukes K.A., Phillips C.F., Kelch R.P., Schaller J.G. Sex differences in academic advancement. Results of a national study of pediatricians. N Engl J Med, 1996. 335: 1282-9.

12. Carr, P.L., Ash A.S., Friedman R.H., Szalacha L., Barnett R.C., Palepu A., Moskowitz M.M. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med, 2000. 132: 889-96.

13. Hamel, M.B., Ingelfinger J.R., Phimister E., Solomon C.G. Women in academic medicine--progress and challenges. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355: 310-2.

14. Sandhu, B., C. Margerison, and A. Holdcroft, Women in the UK academic medicine workforce. Med Educ, 2007. 41: 909-14.

15. Women in Academic Medicine. 2004, British Medical Association.

16. Elston M, A., Women and medicine, the future 2009, Royal College of Physicians: London.

17. Medical Education and Training Unit. Health Services Executive. Implementation of the Reform of the Intern Year. Second interim report, 2012. Accessed on 5/5/12 at: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/corporate/etr/Second%20Interim%20Implementation%20Report%20April%202012.pdf

18. Tesch, B.J., Wood H.M., Helwig A.L., Nattinger A.B. JAMA, 1995. 273: 1022-5.Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA, 1995. 273: 1022-5.

19. De Angelis, C.D., Women in academic medicine: new insights, same sad news. N Engl J Med, 2000. 342: 426-7.

20. Jovic, E., J.E. Wallace, and J. Lemaire, The generation and gender shifts in medicine: an exploratory survey of internal medicine physicians. BMC Health Serv Res, 2006. 6: 55.

21. Lugtenberg, M., Heiligers P.J., de Jong J.D., Hingstman L. Internal medicine specialists' attitudes towards working part-time: a comparison between 1996 and 2004. BMC Health Serv Res, 2006. 6: 126.

22. Carr, P.L., Ash A.S., Friedman R.H., Scaramucci A., Barnett R.C., Szalacha L., Palepu A., Moskowitz M.A. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Intern Med, 1998. 129: 532-8.

23. Ferris, L.E., Mackinnon S.E., Mizgala C.L., McNeill I. Do Canadian female surgeons feel discriminated against as women? CMAJ, 1996. 154: 21-7.