|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Irene Gilroy,Nicole Donnelly,Wayne Matthews,Kirsten Doherty,Greg Conlon,Anna T Clarke,Leslie Daly,C Kelleher,P Fitzpatrick

|

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2013 Apr;106(4):118-20

|

|

I Gilroy1, N Donnelly2, W Matthews2, K Doherty1, G Conlon1, AT Clarke3, L Daly3, C Kelleher3, P Fitzpatrick3

1St Vincent’s University Hospital, Elm Park, Dublin 4

2Dundalk Institute of Technology, Dundalk, Co Louth

3UCD School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Population Science, Belfield, Dublin 4

Abstract

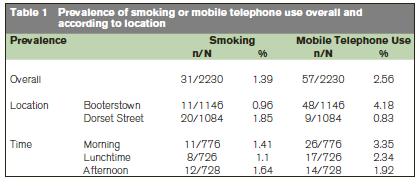

Legislation is being considered which bans smoking in cars carrying children under the age of 16. This was an observational survey of smoking by drivers and passengers and mobile phone use by drivers in 2,230 cars over three time periods in two Dublin locations. The observed prevalence of mobile telephone use (2.56%) was higher than smoking (1.39%) (p<0.01), but was low in both. There was no significant variation according to time of day. There was an inverse pattern according to car value for smoking drivers (p=0.029). Eight adult passengers and just one child were observed as being exposed to a smoking adult driver. In conclusion, the public health importance of regulating passive smoke exposure is clear but the resources required to police such a ban in vehicles may be labour intensive for the yield in detection or prevention.

Introduction

A blanket ban on smoking indoors in the workplace and other public places such as bars and restaurants has been successfully implemented in Ireland since the March 2004 legislation.1,2 However the focus now is on eliminating smoking in cars and other private vehicles where the hazardous air quality is dangerous to both the driver and any passengers in the vehicle, particularly children.3 One of the biggest issues arising from smoking in a vehicle is the risk for the other passengers, particularly non-smokers not otherwise intentionally jeopardising their own health. Evidence from the British Medical Association Board of Science demonstrates that the level of toxins in a smoke-filled vehicle could be 11 times higher than that of, for instance, a smoky bar due to the restrictive internal environment of a vehicle.4 Second hand smoke (SHS) is a group 1 carcinogen and there is no recognised safe level of SHS exposure.5 Children or young people, not yet fully developed physically and thus more at risk, are involuntarily being exposed to the toxins from SHS.6 It is reported in the media that a diverse range of countries plan to, or already have, introduced legislation in this area, including Cyprus, Mauritius, Bahrain, South Africa, United Arab Emirates and some jurisdictions in Australia, Canada and America (http://en.wikipaedia.org/) though there is as yet little systematic evaluation of such legislation in other countries in the literature.7

The Irish government is planning as of 2012 to bring in legislation which bans smoking in cars carrying children under the age of 16. To date there is very little evidence on the prevalence of smoking in cars in Ireland. Studies in North America, the UK and Australasia, show substantial support for smoke-free environments in private vehicles, with more than 77% of smokers agreeing.8 The other lifestyle hazard associated with driving is mobile telephone use. Using a mobile telephone while driving is extremely dangerous, as it affects the driver’s performance, by distracting the driver both cognitively and physically.9 In 2006, a legislative ban was introduced prohibiting the use of handheld mobile phones while driving. Again there is very little systematic evidence from Ireland on the number of people who still do so regardless of legislation. One study found that mobile telephone use while driving was associated with a fourfold increased risk of having a motor vehicle collision.10 The aim of this study was to identify both the prevalence of smoking in vehicles and the use of hand held mobile telephones by drivers.

Methods

This was an observational survey in Dublin city conducted in spring 2012. Two locations were chosen adjacent respectively to UCD teaching hospitals St Vincent’s University Hospital in the south-side and the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in the north-side. Two observers were stationed at both the junction between Booterstown Avenue and the Rock Road, and the junction between North Circular Road and Dorset Street. The observers noted consecutive vehicles which were stopped at traffic lights. Each pair of observers had to record a minimum of 350 vehicles at each time slot (i.e. minimum of 1000 cars in total at each location). The study took place over two days between the times: 08:15 hours to 08:45 hours, 13:45 hours to 14:15 hours, 16:30 hours to 17:00 hours. If a driver or passenger was observed smoking or any driver was using a mobile phone in the car, the following data were recorded on a pre-piloted data sheet: gender, approximate age (<30 years, 30-65 years, >65 years), make, model and year of car, and specifically for smoking, whether the window was open and if there was anyone else in the car (adult, school going child (as determined by uniform) or younger child). For reference purposes an additional observation of all cars was carried out in one observation period at the Booterstown location to record the make, model and year of 200 cars which passed that junction. Data were analysed using SPSS work package; the chi-squared test was used for comparisons of proportions.

Results

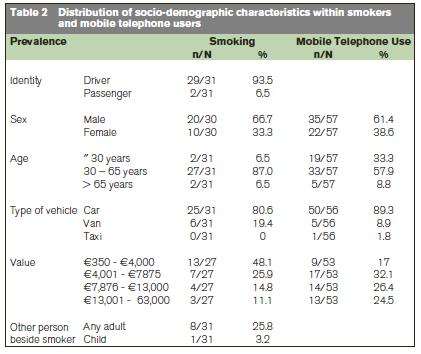

Overall the observed prevalence of both smoking (1.39%) and mobile telephone use (2.56%) was low but the latter was somewhat higher (p<0.01) (Table 1). The observed rate in the south-side location was non-significantly lower for smoking but higher for mobile telephone use (p<0.001). There was no significant variation according to time of day (p>0.05) (Table 1) but more males than females were observed undertaking both activities and most were in the mid age range (Table 2). The majority were in cars rather than in vans or taxis and no lorry-drivers were observed. There was an inverse pattern according to car value for smoking drivers but no clear gradient was observed for mobile telephone use. The rates of smoking according to car value were calculated using the reference information and it was shown that smoking rates decreased markedly as the value of the car rose, from 2.05% in the lowest quartile of value to 0.5% in the highest quartile (p=0.029) but no significant association with car value was observed for mobile telephone usage. Eight adult passengers and just one child were observed as being exposed to a smoking adult driver in the survey.

Discussion

This survey has established a prevalence of both smoking and mobile telephone usage in vehicles in advance of any legislative change in relation to passive smoke exposure to minors in the capital city of the Republic of Ireland. Mobile telephone usage is already legally prohibited but we observed low but appreciable continued use, which was greater in the more affluent observation point. Other surveys in the country report somewhat higher but comparable rates.11,12 There is immediate danger to road users from this practice and it is policed with penalty point sanction, though clearly difficult to enforce absolutely.

The observed prevalence of active smoking was low and the passive smoke exposure in absolute terms was modest in over two thousand vehicles observed, though a quarter of active smokers had an adult passenger who was exposed. By contrast with the mobile telephone utilisation patterns there was a social gradient observed, both at area level in that the rates were higher in the north-side of the city and inversely associated with car value. It is well established that active smoking has a strong social gradient13 so less affluent drivers might be more likely to smoke also in their cars, a finding reported in a study very similar to our own in New Zealand.14 Another observational study in inner city Dublin found a higher prevalence of smoking in vehicles (14.8%)15 but this might simply reflect the location. By contrast with mobile telephone usage, the rationale for banning smoking in cars is to reduce passive smoke exposure and hence is not related to immediate hazard risk but to the health consequences of exposure. Whilst the estimated burden of passive smoke exposure has been calculated the actual database for risk exposure is limited. A recent systematic review of the consequences of legislative bans to control passive smoke exposure included few studies that also measured car exposure.7

We were surprised to observe hardly any obvious work vehicles such as taxis or vans either with a smoking driver or a mobile phone user but both are already illegal under the workplace ban and mobile phone legislation. The public health importance of regulating passive smoke exposure is clear but the resources required to police such a ban in vehicles may be labour intensive for the yield in detecting or preventing the practice. It will take serious consideration by An Garda Síochána as to how in practice this might operate. It is possible that the existing legislation has already indeed had an impact on the practice since social support for that legislation is already very strong.

Correspondence: P Fitzpatrick

UCD School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Population Science, Woodview House, Belfield, Dublin 4

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, Hammond D, Hastings G, McNeill A, Anderson S, Cummings KM, Allwright S, Mulcahy M, Howell F, Clancy L, Thompson ME, Connolly G, Driezen P. Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland. Tobacco Control 2006; 15 (suppl III): iii51–8.

2. Howell F. Smoke-free bars in Ireland: a runaway success. Tobacco Control 2005; 14: 73 – 74.

3. Kabir Z, Manning PJ, Holohan J, Keogan S, Goodman PG, Clancy L. Second-hand smoke exposure in cars and respiratory health effects in children. European Respiratory Journal 2009; 34: 629–633.

4. British Medical Association (BMA) Smoking in Vehicles. London: BMA; 2007.

5. Edwards R, Wilson N, Pierse N. Highly hazardous air quality associated with smoking in cars: New Zealand pilot study. New Zealand Medical Journal 2006; 119: U2294.

6. Sendzik T, Fong GT, Travers MJ, Hyland A. An experimental investigation of tobacco smoke pollution in cars. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2009; 11: 627–34

7. Callinan JE, Clarke A, Doherty K, Kelleher CC. Legislative smoking bans for reducing secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. [Cochrane Review] In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 6, 2010. Oxford: Update Software.

8. Thomson G, Wilson N. Public attitudes to laws for smokefree private vehicles: A brief review. Tobacco Control 2009; 18: 245-61.

9. Brace C, Young K, Regan M. Analysis of the literature: The Use of Mobile Phones While Driving. Australia: Monash University Accident Research Centre (MUARC); 2007.

10. McEvoy SP, Stevenson MR, McCartt AT, Woodward M, Haworth C, Palamara P, Cercarelli R. Role of mobile phones in motor vehicle crashes resulting in hospital attendance: a case-crossover study. British Medical Journal 2005; 331 (7514): 428.

11. Bedford D, O’Farrell A, Downey J, McKeown N, Howell F. The use of hand held mobile phones by drivers in Ireland. Irish Medical Journal 2005; 98: 248.

12. O’Meara M, Bedford D, Finnegan P, Murray C, Howell F. The impact of legislation on handheld mobile phone use by drivers. Irish Medical Journal 2008; 101: 221-2.

13. Morgan K, McGee H, Watson D, et al. SLAN 2007: Survey of Lifestyle,Attitudes and Nutrition in Ireland. Main Report. Dublin: Department of Health and Children; 2008.

14. Martin J, George R, Andrews K, Barr P, Bicknell D, Insull E, Knox C, Liu J, Naqshband M, Romeril K, Wong D, Thomson G, Wilson N. Observed smoking in cars: a method and differences by socioeconomic area. Tobacco Control 2006; 15: 409 – 411.

15. Kabir Z, Keogan S, Manning PJ, Holohan J, Goodman PG, Clancy L. Prevalence of smoking in cars in Ireland: cross-sectional surveys. Irish Journal of Medical Science 2008; 177 Supplement 13: S446.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|