|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Valerie Walshe,M Kennelly

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):44-6

V Walshe, M Kenneally

Health Service Executive, Aras Slainte, Wilton Rd, Cork

Abstract

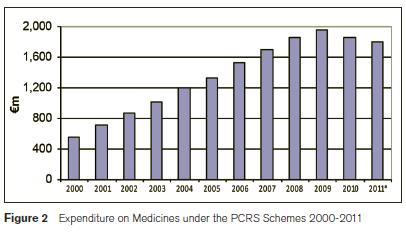

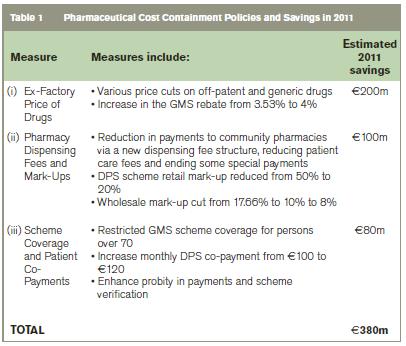

The annual cost of medicines under the community drugs schemes increased from €564m in 2000 to €1,961m in 2009 before falling an estimated 8% by 2011. Escalating public health costs, fiscal stress and the unsustainability of the previous growth in expenditure has led to the increased use of pharmaceutical cost containment measures in Ireland. Collectively, these measures are estimated to have reduced public expenditure on community drugs by €380m in 2011 and involve addressing; 1) the ex-factory price of drugs including price cuts of up to 40% on off-patent and generic drugs leading to an estimated €200m saving (53%); 2) pharmacy dispensing fees and mark-ups via a new dispensing fee structure and reducing both retail and wholesale mark-ups with a €100m saving (26%); and 3) scheme coverage and patient co-payments including restricting scheme coverage for persons over 70 years and increasing the level of co-payments with savings of €80m (21%).

|

Introduction

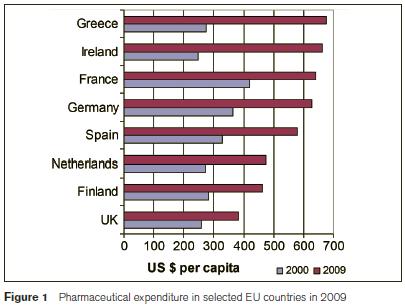

Pharmaceutical spending in the European Union exceeded €180 billion in 2008 and accounted, on average, for around 17% of EU countries’ total spend on health1. The scale and growth of these costs challenge the ongoing sustainability of some national health systems (Council of the European Union 2006) and have compelled rapid policy change in many countries including Ireland. Public health spending in Ireland more than doubled between 2000 and 2008, peaking at €15.186bn1. During this period Ireland had the third fastest growth rate (7.6% p.a.) in per capita real health spending of all OECD countries. In 2009, Ireland spent $3,781 per capita on health, more than the OECD average of $3,223, both adjusted for purchasing power parity1. Also in 2009, Ireland spent $662 per capita on pharmaceuticals, the third highest expenditure in the OECD. Between 2000 and 2009, Ireland’s expenditure on pharmaceutical products increased by 166%, the greatest increase of any EU-15 country, excluding Greece1.

The Irish economy has contracted sharply since 2008. Deep recession, historic fiscal deficits and mounting public debt culminated in an €85bn EU-IMF funding package granted in November 2010 on condition that the Irish government raises taxes and reduces public spending equivalent to 9% of GDP over 2011–142. Faced with such circumstances a government that is unable or unwilling to meet its health system obligations must either; 1) increase public health revenues; 2) weaken public health obligations; or 3) improve health system conversion of resources into value3. While recent Irish policy-making has applied all three remedies its focus has been on the third, containing costs and limiting disruption to the supply of public medical services by seeking greater efficiency4, a theme echoed in The National Recovery Plan 2011-2014 “the focus must be on eliminating inefficiencies ...and [to] lessen the impact on service provision”5. The Health Service Executive (HSE), which is responsible for delivering health and social care in Ireland, saw its net budget fall 9% to €12.5bn over the 2 years to the end of 20116. Expenditure on the Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS – formerly know as the community drugs or the demand-led schemes) fell by 14% to €2.5bn over the same 2 year period6.

Methods

This paper examines recent expenditure trends under the PCRS focusing on pharmaceutical services and the cost of medicines, with particular reference to the General Medical Services (GMS – also know as the medical card) scheme. It also identifies the main measures recently adopted to contain public sector pharmaceutical costs in Ireland and provide estimates of full year savings for 2011. The main policies recently adopted are examined under three headings; 1) the ex-factory price of drugs; 2) pharmacy dispensing fees and mark-ups; and 3) scheme coverage and patient co-payments.

Results

In 2010, the HSE spent €3.2bn (23% of its total expenditure) on primary care and medical card schemes. Over 64% (€2bn) of this expenditure was on pharmaceutical services. After this, the largest expenditure items were doctors’ fess and allowances and capitation payments at 15% (€496m) and 13% (€420m) respectively7. The annual cost of medicines under the community drugs schemes increased by nearly 350% from €564m in 2000 to €1,961m in 2009, before falling more back in 2010 and 20118. Between 2000 and 2009 annual expenditure increases ranged between 6% and 27% however in 2010 a 5% decrease was recorded and in 2011 provisional figures have the decrease at slightly smaller.

The GMS scheme, the largest community drugs scheme covers 1.7m people who are unable to pay for medical services, including prescribed drugs, “without undue hardship”. More than 78,000 additional persons (5%) were covered by this scheme in 2011 and an additional 1.2m prescriptions (7%) were reimbursed6. The number of items dispensed under the scheme increased from 54m in 2010 to 57m in 2011 while the average ingredient cost per item fell. Total prescription costs under the scheme fell slightly in 2011 from €1.22bn in 20108. In 2010, the average cost of medicines supplied to each person under the GMS scheme was €763, a 12% decrease on the previous year. The cost of medicines varies greatly by age and gender. For example, in the same year medicines for the average 5-11 year old was just under €84 whereas, it was €1,791 for person over 75 years. Regional variations also exist with the average cost of medicines for a person claiming from the southern region being €842 versus only €626 for the average claimant in the north western region. Aspirin was the most frequently prescribed medication with nearly 2.6m items prescribed. Atorvastatin (Lipitor) was the number one selling drug with an ingredient cost of over €71m under this scheme alone in 20108. The PCRS expenditure growth experienced over the last decade is unsustainable and has resulted in the implementation of various pharmaceutical cost containment measures in Ireland, the results of which have materialised in decreasing expenditure trends in 2010 and 2011. The main measures and the 2011 financial impact are estimated as follows:

The ex-factory price of drugs

A 2006 agreement between the HSE and the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association on pricing and supply of medicines is estimated to have delivered total savings of €250m by September 20104. It references and links the price of new medicines in Ireland to nine EU member states. The agreement also included a 35% two phase price reduction for all off-patent medicines with a generic equivalent i.e. 20% reduction in March 2007 followed by a further 15% price reduction in January 2009. There was a further 40% price reduction in February 2010 resulting in a final price of 39% of the original proprietary drug price. In addition to this there was also an increase in the GMS rebate from 3.53% to 4% in January 2010. This agreement has been extended to 2012 and applies to all medicines granted marketing authorisation by the Irish Medicines Board or European Commission that can be prescribed and reimbursed under the community drugs schemes and all medicines supplied to the HSE including state funded hospitals/agencies. Since the expiration of this agreement further full year savings of €20m off the price of certain post patent medicines has been agreed9. These measures have reduced the prices of over 1,000 medicines since the beginning of 2011 and are intended to ensure that the HSE no longer pays a premium price for patent-expired medicines10.

Pharmacy dispensing fees and mark-ups

The Report of the Independent Body on Pharmacy Contract Pricing resulted in a restructuring of the GMS pharmacy dispensing fee system11. From 2009, the new GMS fee-per-item is stepped; the fee-per-item pharmacies receive falls as the number of items dispensed exceeds given thresholds. The HSE reduced both the DPS (Drugs Payments Scheme) pharmacy retail mark-up on medical ingredients from 50% to 20% and the wholesale factory-to-pharmacy mark-up from 17.66% to 10% in July 2009. This mark-up was reduced to 8% in March 2011 along with a 50% reduction in the patient care fee under the High Tech Drugs scheme.

Scheme coverage and patient co-payments

The Minister restricted GMS coverage for high-income persons over 70 in January 2009 and increased the DPS patient co-payments from €100 to €120 a month in the 2010 budget with a further €12 increase announced for 2012. A €0.50 charge per GMS item was also introduced in October 2010. These measures effectively enhanced fiscal sustainability and are estimated to have reduced the annual cost of pharmaceuticals under the PCRS by €380m in 2011. Table 1 summarises these details:

Discussion

The HSE states that three components govern the costs under the community drugs schemes namely the numbers of persons eligible for the drugs/services, the drugs/services supplied and the volume of these drugs/services6. Over the past 2 years, both the number of persons covered and the number of items dispensed under the medical card scheme have been increasing while the cost of the drugs has decreased. The overall result has been a significant reduction in community drug expenditure. Various other cost containment measures are planned for 2012 including reference pricing and generic substitution, following the introduction of the appropriate legislation12. Reference pricing involves identifying a group of interchangeable medicines (e.g. generic equivalents) and setting a maximum reimbursement price for the group. A physician is able to prescribe the brand/drug of choice and the patient can have the brand/drug of choice but the State shall only reimburse the value of the lowest priced medicine in the group. Generic substitution allows for a pharmacist to substitute interchangeable medicines providing the patient with a choice within the group of medicines. Other measures proposed, but not yet fully adopted, include reductions in the price of patent protected drugs, reviewing the reimbursement status of clinical nutritional and similar products, and the increased use of cost-effectiveness analysis. Increased expert feedback to general practitioners (GPs) on quality prescribing indicators is also being proposed. Particular drug initiatives in relation to over prescribing to identify at GP and hospital level where cost efficiencies can be achieved are also being planned. It is hoped that these reforms will promote price competition among suppliers and ensure that lower prices are paid for these medicines resulting in significant savings.

In Ireland, particular concerns over sustainability have arisen with regard to public expenditure on the PCRS13-15. Health system sustainability has been defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the “ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability to meet future needs”. A health system is fiscally sustainable if government is able and willing to meet its health system obligations. It is economically sustainable “so long as the value produced by health care exceeds its opportunity cost”3. Fractured national public finances, headline deficits, and the elevated fiscal risks recently noted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have impaired the funding capacity of the Irish government and focussed increasing policy attention on fiscal sustainability16. Fiscal stress arising from escalating public health costs has resulted in increasing Irish and international reliance on pharmaceutical cost containment measures.

Tele (2009)17 and Barros (2010)18 assess the effectiveness of various cost containment measures for pharmaceutical expenditure across the EU-27. These include international referencing to benchmark countries with lower prices, internal reference pricing systems to promote price competition in domestic markets, and positive lists for reimbursement to promote consumption of generics. Barros found that few measures are universally effective (apart from generic substitution combined with reference pricing). Some, such as positive lists, prescribing budgets and reference pricing, were effective in some countries but only in the short-term. A consensus policy strategy that ensures fiscal and economic sustainability, however, has not yet crystallised.

Correspondence: V Walshe

HSE, Aras Slainte, Wilton Rd, Cork

Email: [email protected]

References

1. OECD Health Data 2011 – Frequently requested data. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/document/30/0,3746,en_2649_37407_12968734_1_1_1_37407,00.html. [Accessed March 15, 2012].

2. IMF. Country Report No 10/366 Staff Report on Ireland 2010. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2010/cr10366.pdf. [Accessed May 25, 2011].

3. Thomson S, Foubister T, Mossialos E. Financing Healthcare in the European Union. World Health Organization 2009 on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/98307/E92469.pdf. [Accessed August 12, 2011].

4. Department of Health and Children. Health Estimates for 2010. Available from: http://www.dohc.ie/press/releases/2009/20091209.html. [Accessed March 2, 2012].

5. Department of Finance. The National Recovery Plan 2011-2014. Available from: http://www.budget.gov.ie/The%20National%20Recovery%20Plan%202011-2014.pdf. [Accessed March 2, 2011].

6. Health Service Executive. Performance reports monthly. Detailed financial data. Dec 2011 supplementary report. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/corporate/performancereports/2011prs.html [Accessed April 26, 2012].

7. Health Service Executive. Annual report and financial statements 2010. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/corporate/annualrpt%202010.html [Accessed Feb 26, 2012]

8. Health Service Executive. Primary Care Reimbursement Service, Financial and Statistical Analysis various years. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/PCRS/PCRS_Publications/. [Accessed April 15, 2012].

9. Department of Health and Children. Minister of Health Dr James Reilly announces drug price cuts. Available from http://www.dohc.ie/press/releases/2012/20120618.html. {Accessed July 31, 2012].

10. Tilson L, Bennett K, Barry M. The potential impact of implementing a system of generic substitution on the community drug schemes in Ireland. Eur J Health Economics 2005;50:267–73.

11. Department of Health and Children. The Report of the Independent Body on Pharmacy Contract Pricing Report. 2008. Available from: http://www.dohc.ie/publications/pdf/pharmacy_contract_pricing.pdf?direct=1. [Accessed May 15, 2011].

12. Department of Health & Children. Minister Roisin Shorthall announces primary care measures in budget 2012. Available at: http://www.dohc.ie/press/releases/2011/20111205c.html [Accessed April 22, 2012]

13. Barry M, Usher C, Tilson L. Public drug expenditure in the Republic of Ireland. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2010;10:239–45.

14. Brick A and Nolan A. Research Series Number 18, October 2010. Budget perspectives 2011.(ed T. Callan) The sustainability of Irish health expenditure. Oct 2010. Available from: http://www.esri.ie/publications/search_for_a_publication/search_results/view/index.xml?id=3114. [Accessed August 25, 2011].

15. The Economic and Social Review Institute. Pharmaceuticals delivery in Ireland: Getting a bigger bang for the buck. Available at: http://www.esri.ie/publications/latest_publications/view/index.xml?id=3441. [Accessed April 26, 2012]

16. International Monetary Fund. Fiscal Monitor April 2010. Shifting gears, tackling challenges on the road to fiscal adjustment. 2011. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2011/01/pdf/fm1101.pdf. [Accessed May 5, 2011].

17. Tele P, Groot W. Cost containment measures for pharmaceuticals expenditure in the EU countries: A comparative analysis. The Open Health Ser and Policy J. 2009; 2: 71-83. Available from: http://www.benthamscience.com/open/tohspj/articles/V002/71TOHSPJ.pdf. [Accessed July 4, 2011].

18. Barros PP. Pharmaceutical policies in European countries. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res 2010;22:3-27.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|