Introduction

Studies have shown that post cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation, systemic cooling to a bladder temperature between 32°C and34°C for 24 hours improves outcomes1,2. On the basis of this evidence Therapeutic Hypothermia (TH) was introduced in the 2002 International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) guidelines3 and recommended in European Resuscitation Council (ERC) 2005 guidelines4. The QT interval is the time interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG) between the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of T wave. Its prolongation can lead to polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes5. Acquired QT prolongation can be due to a variety of different causes including hypothermia6, the subject of this study. In this study we performed a retrospective review of all patients who received TH in our hospital over a period of 2 years to assess the effect of TH on QTc and any possible arrythmogenesis.

Methods

This is a retrospective case review study. Case records were reviewed to collect data on all patients who received therapeutic hypothermia for VF/VT cardiac arrest in our hospital between Jan 2009 and May 2011. Patients with paced rhythm were excluded. Baseline case characteristics were noted. All ECGs and QTc intervals were assessed in relation to core body temperature before during and after TH. Other factors influencing QT interval were also assessed. Cooling was performed in all patients by the Blanketrol III system (Cincinnati Sub-Zero, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Core body temperature was monitored by urinary bladder probes. Continuous telemetry rhythm monitoring was performed on all patients. All ECGs were performed on a Philips Pagewriter, XLi machine and the QTc measurement as calculated by the programmed machine algorithm was accepted. In the presence of a bundle branch block, Bazett’s formula was used on manual measurement of QT interval in which QRS duration was assumed at 120ms. Microsoft Excel 2004 Mac edition software was used to analyze the data.

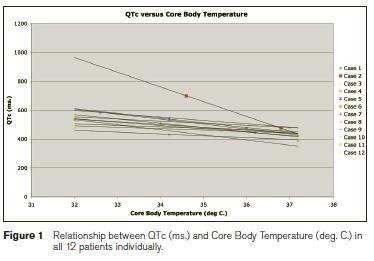

Figure 1: Relationship between QTc (ms.) and Core Body Temperature (deg. C.)in all 12 patients individually.

Results

A total of 13 patients received TH for VF/VT cardiac arrest during the 2.5 years between Jan 2009 and July 2011. One patient with a paced rhythm was excluded, and the remaining 12 patients were included in the study (n=12). Eight patients were male and four were female, and the average age was 63 years. The substrate for cardiac arrest was ischemic in 7 patients (58 %) and non-ischemic in 5 patients (42 %). Echocardiography showed left ventricular (LV) function was normal in 4 patients and impaired in remaining 8 patients. The average duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before return of spontaneous circulation was 8 minutes. Four patients died and eight patients had a complete recovery; of these patients, four received an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD). The average duration of TH was 27.25 hours. QTc prolongation was observed in all patients, and was more pronounced in patients who received Amiodarone concurrently. At the end of TH the QTc interval returned to baseline in all patients. The average prolongation of QTc was 80.3+57.2 ms, and continuous rhythm monitoring of all these patients did not record any episodes of torsades de pointes in spite of QT prolongation.

QTc prolonged into the abnormal range in all but 1 patient; the average QTc at lowest body temperature was 533+64.5 ms. Four patients received Amiodarone before or during the process of hypothermia either as a single bolus or infusion. These patients demonstrated a greater degree of increase in QTc,(cases 2,7,8 and 11) with an average increase of 109.7+80.4ms. This compared to average increase of 65.6+40.4 ms. in patients who did not receive Amiodarone.

Discussion

Our study adds to the existing evidence illustrating QTc prolongation in patients undergoing TH following cardiac arrest due to VT or VF7-9. In spite of significant prolongation of QTc no arrhythmia such as torsades de pointes was seen. TH appears a safe procedure but careful monitoring of QTc is advisable particularly in those patients receiving Amiodarone.

Correspondence: A Riaz

Cardiology Department, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Elm Park, Dublin 4

Email: [email protected]

References

1.The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. Feb 21 2002;346:549-556.

2. Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, Smith K. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. Feb 21 2002;346: 557-563.

3. Nolan JP, Morley PT, Vanden Hoek TL, Hickey RW, Kloeck WGJ, Billi J. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: an advisory statement by the advanced life support task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. Jul 8 2003;108:118-121.

4. Wenzel V, Russo S, Arntz HR, Bahr J, Baubin MA, Bottiger BW. [The new 2005 resuscitation guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council: comments and supplements]. Anaesthesist. Sep 2006;55(9):958-966, 968-972, 974-959.

5. El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Torsade de pointes. Curr Opin Cardiol. Jan 2003;18:6-13.

6. Aslam AF, Aslam AK, Vasavada BC, Khan IA. Hypothermia: evaluation, electrocardiographic manifestations, and management. Am J Med. Apr 2006;119:297-301.

7. Khan JN, Prasad N, Glancy JM. QTc prolongation during therapeutic hypothermia: are we giving it the attention it deserves? Europace. Feb 2010;12:266-270.

8. Milanovic R, Husedzinovic S, Bradic N. Induced hypothermia after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: possible adverse effects. Signa Vitae 2007;2:15-7.

9. Griffiths J. Out of hospital cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Anaesthesia UK 2007. Online article http://www.anaesthesiauk.com/article.aspx?articleid=100737#