|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aisling Smith,Stephen Mannion

|

|

|

Ir Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):50-2

A Smith, S Mannion

Department of Anaesthesiology, South Infirmary University Hospital, Cork

Abstract

Patients are often unaware of the extensive duties of an anaesthetist and their significant contributions to patient management. This study aimed to evaluate current knowledge and perceptions of anaesthesia among an Irish patient population. 100 surgical patients completed multiple choice questionnaires which assessed patients knowledge of anaesthesia, the role of an anaesthetist and satisfaction with the consent process. 62 (62%) patients attributed their knowledge of anaesthesia to a previous operation and 78 (78%) patients knew that anaesthetists were qualified doctors. 30 (30%) patients were unaware that anaesthetists are involved in activities outside of the operation theatre. 44 (44%) patients wanted to be informed pre-operatively of all possible risks that can occur with anaesthesia and 82 (82%) would find an anaesthetics information leaflet helpful. 48 (48%) patients reported feeling anxious/fearful about undergoing anaesthesia. This data confirms existing research in other countries which indicates a need to further educate Irish patients about the roles of the anaesthetist and how anaesthesia is conducted.

|

|

Introduction

The clinical specialty of anaesthetics has its origins in Jefferson, Georgia, U.S.A, where, on the 30th of March 1842, Dr. Crawford Williamson Long used an ether soaked towel to render his patient, Mr. James Venable, insensible to pain during the surgical excision of a tumour from his neck. In 1844 Horace Wells used nitrous oxide for tooth extraction and in 1846 William Thomas Green Morton publicly demonstrated the use of inhaled ether as a surgical anaesthetic at the operating theatre of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA1. From such humble beginnings anaesthetics has evolved, establishing itself as an independent and sophisticated field of medicine. Although the triad of analgesia, hypnosis and muscle relaxation still remains the fundamental principle underlying general anaesthesia for surgery, the domain of anaesthesia has now extended far beyond the exclusive remit of the operating theatre. Anaesthetists are multi-skilled physicians who possess a thorough knowledge of internal medicine, physiology, pharmacology, pain management and surgical procedures. While the primary purpose and concern of anaesthetists is to ensure patients safety and stability prior to, during and after surgery, their role has expanded to encompass such areas as the management of acute and chronic pain, intensive care medicine and the emergency management of critically ill and trauma patients.

However, despite the significant role anaesthetists have in hospital activities, many patients are unaware of the extensive duties of an anaesthetist and the central role they often play in their management. The treatment provided by anaesthetists is often intensive in nature, of limited duration and frequently unseen by the patient who benefits from their care. Such circumstances may adversely affect the relationship between anaesthesia patients and their anaesthetist as well as facilitating the potential development of inaccurate impressions of anaesthesia overall. The aim of this study was to evaluate current knowledge and perceptions of anaesthesia among an Irish surgical patient population.

Methods

This study was approved by the Cork Research and Ethics Committee. This was a cross-sectional study and questionnaires were distributed between March and April 2011 at the South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital, Cork. This hospital is a university teaching hospital with a variety of surgical specialties including General Surgery, ENT Surgery and Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 100 Irish patients independently completed an anonymous written questionnaire, which consisted of 19 multiple choice questions. Inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age, post-operative and who had their anaesthesia administered by an anaesthetist. This was to ensure that all participating patients had the opportunity to meet an anaesthetist before partaking in this study. Patients with abnormal mental status were not eligible to participate in this research.

Results

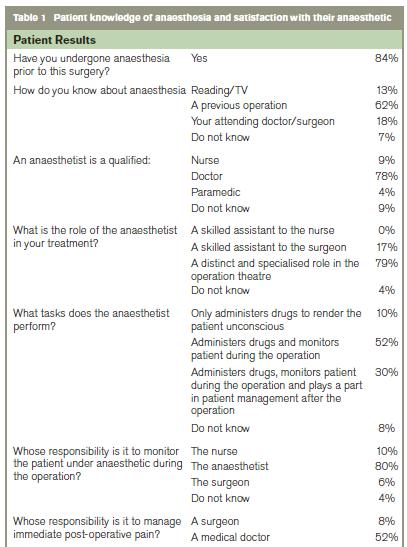

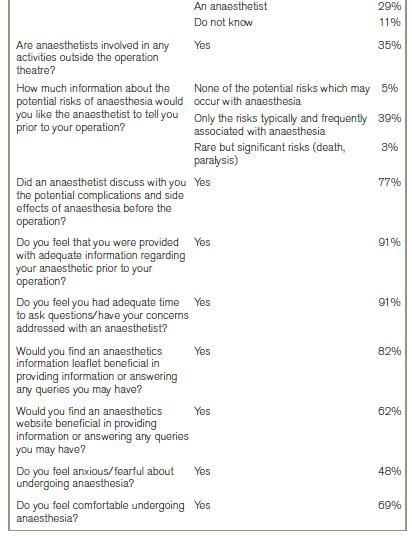

All patients who consented completed the survey. This survey was broadly divided into two sets of questions, the results of which are displayed in the table below. The first set of questions sought to establish the patients knowledge of the role of an anaesthetist, their tasks and responsibilities (Table 1). The second set of questions was designed to ascertain the patients satisfaction with their anaesthetic, communication with the anaesthetist and the consent process (Table 1).

Discussion

Of the 100 patients surveyed, 78% were aware that anaesthetists are qualified doctors, a figure which is significantly higher than that recorded in several other studies. Chew et al, Hariharan et al and Klafta et al reported that just 56.8%, 59% and 65% of patients surveyed in Caribbean, Singaporean and British populations respectively recognised that anaesthetists were qualified doctors2-4. However, Ahsan-Ul-Haq et al recorded that 82% of patients they surveyed in a Pakistani hospital knew this fact5. A review by Klafta et al4 states that ‘The percentage of patients who thought their anaesthetist was medically qualified ranged from 50% to 88.7%’ across several studies, therefore the figure of 78% reported in this study suggests that Irish patients are relatively well informed when compared to other populations.

79% of patients correctly identified that the anaesthetist has ‘A distinct and specialised role in the operating theatre’ and 80% of patients knew that the anaesthetist is the professional responsible for monitoring the patient under anaesthetic during the operation. However, two thirds of patients do not know the extended role of anaesthetists in the post operative period. Only 29% of those surveyed correctly believed that the anaesthetist was responsible for analgesia in the recovery period, a similar figure to the 23.5% recorded by Chew et al2. Just 30% correctly realised that the anaesthetist ‘plays a part in patient management after the operation’ in addition to administering drugs and monitoring the patient during the operation. 35% of patients surveyed did not know whether anaesthetists were involved in any activities outside of the operating theatre and 30% incorrectly answered that they were not. Swinehow and Groves reported that only 25% of their survey respondents were aware that anaesthetists have other hospital responsibilities outside of the operating theatre and, although this survey found that 35% of patients were aware that they did, it demonstrates that a significant proportion of Irish patients may be completely unaware of the variety of tasks anaesthetists perform in the hospital such as the administration of epidural anaesthesia to those in labour and the management of intensive care patients7. There are a number of potential reasons as to why patients would be uninformed of the extensive duties of an anaesthetist. Anaesthetists now perform many tasks once carried out by medical physicians or surgeons and in recent year many sub specialties within anaesthesia have emerged including ambulatory care anaesthesia, critical care anaesthesia the management of patients with acute and chronic pain.

The majority of patients, 44%, wanted to know all the possible risks that can occur with anaesthesia, a figure considerably lower than that reported by Irwin et al, where 90% ‘preferred to know all the possible complications of an anaesthetic, no matter how serious they were’8. Of note is that this survey was conducted only on post-operative patients and as such these results may be quite different than if the patients had been surveyed pre-operatively when discussions of potential anaesthetic risks, such as death or paralysis, may or may not be welcomed by or appropriate for the patient. Future studies asking patients this question both pre-and post operatively and comparing the data may establish a more accurate representation of how much information regarding the risks of anaesthesia patients truly would like to be made aware of. Such information is important in the context of the patient consent process for anaesthesia. The consent process for anaesthesia can be variable between institutions, is often performed by medical physicians or surgeons and may be included as part of the surgical consent process in many hospitals. Legally patients must grant informed consent for their anaesthetic procedure and be fully aware of any possible risks or side effects of their anaesthetic. However, an appropriate balance must be made between informing the patient of the risks anaesthesia carries without causing undue anxiety or stress. Our data, in the context of the Irish surgical patient, may be useful in guiding anaesthetists during their pre-operative consults with patients by granting them a rationale for how in depth their explanation of the risks of anaesthesia should be9.

In this study the vast majority of patients, at 77%, reported that the complications and side effects of anaesthesia were explained to them prior to the procedure, a significantly higher percentage than the 46% reported in the survey of Hariharan et al3. The majority of patients would also appreciate an anaesthesia leaflet and website. Such tools, as well as press releases, the publication of research and open days similar to the UK National Anaesthesia Day, would be useful for outlining the diversity of hospital activities anaesthetists participate in, encouraging utilisation of sub specialty services and also for pre-empting and answering frequently asked questions, thereby allowing pre-operative anaesthetic consults with patients to become more time efficient and effective10. Access to such information can also have a powerful effect in reducing patient anxiety regarding their anaesthetic11. 48% of patients surveyed in this study answered yes to feeling anxious/fearful about undergoing anaesthesia, a figure higher than the 25% stated by McGaw and Hanna but lower than the 60% reported by Ahsan-Ul-Haq et al5,6. Despite this 69% felt comfortable undergoing anaesthesia, in keeping with the vast majority of patients who indicated that they received adequate information regarding their anaesthetic and had sufficient time to ask questions and have their concerns addressed with an anaesthetist.

Limitations of this study are that it was conducted in an adult, surgical population and although this would represent the majority of patients undergoing anaesthesia, other sub populations, such as obstetric, paediatric and psychiatric patients, were not included in this research. Additionally, this study was conducted in one university hospital in Cork, and therefore future studies in other hospitals within and outside of Cork would be useful in providing additional information regarding the issues assessed in this survey. In conclusion, the general public has a significant interest in medicine and healthcare and, as such continual evaluation of public opinion and perceptions of the medical profession is an imperative. This survey demonstrated a high level of patient satisfaction with regard to their interactions and communication with the anaesthetist. The 100 patients surveyed had a relatively good understanding of the qualifications and role of the anaesthetist within the operating theatre. However, patients displayed a general lack of knowledge of the responsibilities of the anaesthetist in hospital activities outside of the operating theatre, for example, the management of chronic pain, running intensive care units or the administration of epidural anaesthetics on labour wards.

Correspondence: A Smith

C/O Stephen Mannion, Department of Anaesthesiology, South Infirmary University Hospital, Cork

Email: [email protected]

References

1. Collier J, Longmore M, Turmezei T, Mafi AR. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties, 8th edition, 2008.

2. Chew ST, Tan T, Tan SS, Ip-Yam PC. A survey of patients’ knowledge of anaesthesia and perioperative care. Singapore Med J. 1998; 39: 399-402.

3. Hariharan S, Merritt C, Chen D. Patient perception of the role of anaesthesiologists: a perspective from the Caribbean. J Clin Anesth. 2006; 18: 504-9.

4. Klafta JM, Roizen M. Current understanding of patient’s attitudes toward and preparation for anesthesia: A review. Anesthe Analg. 1996; 83:1314-21.

5. Ahsan-Ul-Haq M, Azim W, Mubeen M. A survey of patients’ awareness about the peri-operative role of anaesthetists. Biomedica. 2004; Vol. 20.

6. McGaw CD, Hanna WJ. Knowledge and fears of anaesthesia and surgery. The Jamaican perspective. West Indian Med J. 1998; 47: 64-67.

7. Swinhoe CF, Groves ER. Patient’s knowledge of anaesthetic practice and the role of anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 1994; 49: 165-6.

8. Irwin MG, Fung SKY, Tivey S. Patient’s knowledge of and attitudes towards anaesthesia and anaesthetists in Hong Kong. HKMJ. 1998; Vol 4 No 1.

9. The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Consent for Anaesthesia, Revised Edition (2006).

10. Goldstone, J. National Anaesthesia Day, 8 November 2002. Bulletin 16 The Royal College Of Anaesthetists, November 2002.

11. Kiyohara LY, Kayano LK, Oliveira LM, et al. Surgical Information Reduces Anxiety in the Pre-Operative Period. Rev. Hosp. Clín. Fac. Med. S. Paulo (2004) 59:51-56.

|

|

|

|

Author's Correspondence

|

|

No Author Comments

|

|

|

Acknowledgement

|

|

No Acknowledgement

|

|

|

Other References

|

|

No Other References

|

|

|

|

|